This is the fifth in my weekly series of reflections on Nicole Roccas’s book TIME AND DESPONDENCY: REGAINING THE PRESENT IN FAITH AND LIFE, which I’m reading during this season of Great Lent. If you missed my first four posts and would like to catch up, here they are, in order from first week through fourth:

This is the fifth in my weekly series of reflections on Nicole Roccas’s book TIME AND DESPONDENCY: REGAINING THE PRESENT IN FAITH AND LIFE, which I’m reading during this season of Great Lent. If you missed my first four posts and would like to catch up, here they are, in order from first week through fourth:

This week Roccas’s study guide has us reading Chapter 5, “Prayer and Despondency,” which is the first chapter in Part II of the book. She starts by saying that prayer is “a journey toward a new way of being, a new mode of perceiving the world outside the default of despondency.” Sounds good, right? Especially to anyone who struggles with despondency, to any degree. But it seems like a catch 22 because it’s difficult to pray when we’re despondent, so Roccas starts with some inspiration from one of my favorite writers, Henri Nouwen:

Prayers connects my mind with my heart, my will with my passions, my brain with my belly…. Without prayer we begin to disintegrate—fall out of integration with ourselves, our neighbor, and God.

Our passions—and especially for me my belly—definitely need to be connected to our wills, and that can happen through prayer. Roccas talks about two kinds of prayer, which she calls doing and being. The doing part of prayer can be reciting learned prayers, lighting candles, making prostrations, the physical side of prayer. The being part is the interior mode:

Most often, this is experienced as ‘becoming’ rather than simply being; prayer is the expression of our relationship with God….

But then she says “Despondency attacks both the doing and being modes of prayer in different ways.” And she explains how. Including a section on prayer as “monologue or dialogue” and encourages us to open ourselves up to God in a conversation rather than just talking to Him. She returns to Nouwen for more about this:

…converting our unceasing thinking into unceasing prayer moves us from a self-centered monologue to a God-centered dialogue. To pray unceasingly is to lead all our thoughts out of their fearful isolation into a fearless conversation with God.

How do we do this? Roccas shares wisdom from Dr. Philip Mamalakis , in an article about Orthodox pastoral approaches to marriage, that it is “a long proess of learning to ‘turn toward’ your partner.” She compares this to our relationship with God, in which we need to turn toward Him… not just in the big moments, but (here comes the part about TIME) moment by moment, in the small things. As she says:

If there’s any aspect of prayer that will make sense to us in despondency, it’s the short and steady rather than the excessive and unsustainable…. It is in prayer that we learn not only how to reoccupy the present, but more generally how to mark time. It is the way we come to see, gradually and dimly, the life-giving potential of each moment.

On the practical side, Roccas gives us stepping stones to learn how to make use of our times of both labor and leisure to turn towards God. The church fathers have always seen light manual labor as a source of healing from despondency, and this can be done with activities as simple as folding laundry. I could relate to this because I actually like to do laundry. I see it as a nice break in the intense labor of writing. I don’t necessarily pray while I’m folding our clothes, but my mind tends to rest from its normal busy state as I remove my husband’s shirts from the dryer (I love the way they smell) and smooth them and place them on hangers. Also folding our casual clothes and our towels, creating neat little stacks on the bed—a visual show of something accomplished without a great deal of mental energy. As Roccas says:

On the practical side, Roccas gives us stepping stones to learn how to make use of our times of both labor and leisure to turn towards God. The church fathers have always seen light manual labor as a source of healing from despondency, and this can be done with activities as simple as folding laundry. I could relate to this because I actually like to do laundry. I see it as a nice break in the intense labor of writing. I don’t necessarily pray while I’m folding our clothes, but my mind tends to rest from its normal busy state as I remove my husband’s shirts from the dryer (I love the way they smell) and smooth them and place them on hangers. Also folding our casual clothes and our towels, creating neat little stacks on the bed—a visual show of something accomplished without a great deal of mental energy. As Roccas says:

There is humble creativity in performing ordinary tasks like making the bed or folding clothes—jobs that must be redone day after monotonous day and that fail to amount to anything momentous in the end. Yet such tasks are intensely creational—they bring a new layer of order and beauty into the world we inhabit. When we can manage such tasks with even a hint of grace and care, they are transfigured into something holy.

She goes on to help us learn to “nurture a more meaningful practice of leisure,” saying that “Long-term spiritual growth is sustained by balancing activity with restful contemplation.” This part get tricky since despondency can feed on laziness, but she clarifies:

I would add that perhaps laziness itself doesn’t consist of excessive rest but is instead a symptom of a broken, fallen form of rest.

Indeed. She mentions the difference in restorative rest and the mindless “vegging out” we often do with binge-watching Netflix. This is definitely something I need to work on and will focus on more intensely for the remainder of Lent. This week I will choose, from her suggested “stepping stones for the journey,” this one:

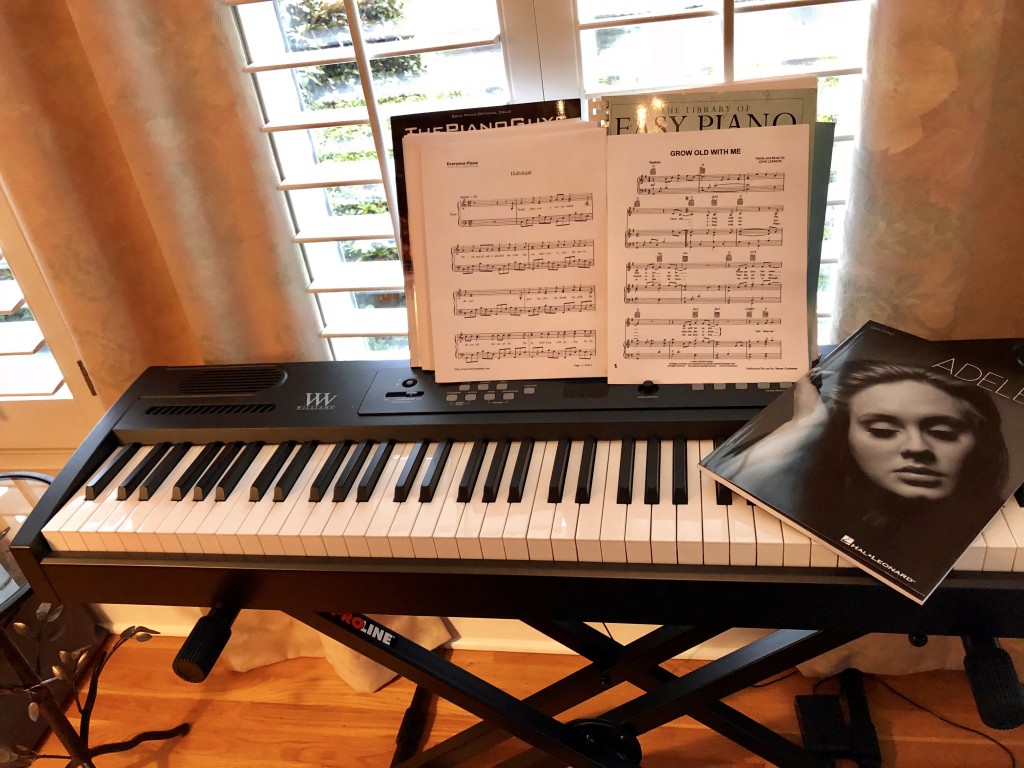

Choose your rest. I will develop a list of activities that are both restful and re-creational rather than mindless (like Netflix). Roccas’s suggestions include taking a walk to observe nature, or even a longer break like visiting an art museum. One thing that hit me as I read this section was that two years ago my husband gave me a really nice electronic keyboard for my birthday. For a while I sat down at the keyboard for a few minutes every day to play something (I took lessons in my youth) but I found it to be more difficult than I remembered, so I gradually quit playing. Maybe I can recover this as a re-creational activity and find in those moments of creating music some rest from the other areas of labor in my brain and body. Today I will begin again with a book of Adele’s songs. Oh, and one from John Lennon that I love, “Grow Old With Me.” And here’s a bonus… while sitting at my piano keyboard, I can see our Japanese cherry blossom tree blooming outside out living room windows. And somehow these moments of rest bring me joy and turn my heart towards God.