When was the last time you read a book that knocked your socks off? The experience I just had—with Donna Tartt’s latest novel, The Goldfinch—was so incredible that I’m embarrassed to try to describe it with words. Because my words can’t hold a candle to hers! I had so many emotions while reading Tartt’s 771-page tome that I hardly know where to begin.

When was the last time you read a book that knocked your socks off? The experience I just had—with Donna Tartt’s latest novel, The Goldfinch—was so incredible that I’m embarrassed to try to describe it with words. Because my words can’t hold a candle to hers! I had so many emotions while reading Tartt’s 771-page tome that I hardly know where to begin.

But I’ll start with the first thing that wowed me about the book—the writing. The words. The metaphors. The descriptions. I found myself thinking over and over as I was reading, “How does she come up with these words? With these magical sentences?” As I return to the difficult work of finishing revisions on my novel, I find myself jealous of her talent. But also with a renewed commitment to a work ethic—Tartt spends about ten years on each novel she writes. And they have all three been blockbusters. But back to the words. A sampling:

…I saw, really saw, looking back down the years with all clear-headed and articulate despair, that the world and everything in it was intolerably and permanently fucked and nothing had ever been good or okay, unbearable claustrophobia of the soul….

Claustrophobia of the soul. Doesn’t that speak volumes about the protag’s state of mind?

Tartt captures the book’s diverse settings—New York City, Las Vegas, and Amsterdam, in particular—with details, large and small, that bring each location tangibly into view. Like this scene in Amsterdam:

On the street: multicolored neon angels, in silhouette, leaning out from the tops of the buildings like ship figureheads. Blue spangles, white spangles, tracers, cascades of white lights….

And this one:

I stirred at the potato mess with my fork and felt the strangeness of the city pressing in all around me, smells of tobacco and malt an nutmeg, café walls the melancholy brown of an old leather-bound book and then beyond, dark passages and brackish water lapping, low skies and old buildings all leaning against each other with a moody, poetic, edge-of-destruction feel, the cobblestoned loneliness of a city that felt—to me, anyway—like a place where you might come to let the water close over your head.

Tartt paints each character with as fine a brush as she uses on settings. Like Theo’s mother—seen through the eyes of an adoring and grieving son:

She was beautiful… And yet she was wholly herself: a rarity…. She had black hair, fair skin that freckled in summer, china-blue eyes with a lot of light in them; and in the slant of her cheekbones there was such an eccentric mixture of the tribal and the Celtic Twilight that sometimes people guessed she was Icelandic…. She moved with a thrilling quickness, gestures sudden and light, always perched on the edge of her seat like some long elegant marshbird about to startle and fly away.

And Theo’s impressions of his father’s house in Vegas, having lived in New York City for all of his life until then:

The twilights out there were florid and melodramatic, great sweeps of orange and crimson and Lawrence-in-the-desert vermilion, then night dropping dark and hard like a slammed door…. The days were clear and beautiful; and, as September rolled around, the hateful glare gave way to a certain luminosity, a dusty, golden quality.

You can see it, right? And these are just a few samples… the book is FULL of them.

But Tartt’s characters are drawn with even more vivid descriptions and depth. All multi-dimensional—the good guys and bad guys alike. And isn’t that what real people are like? In this passage, Theo describes Pippa and his feelings for her:

She was the missing kingdom, the unbruised part of myself I’d lost with my mother. Everything about her was a snowstorm of fascination, from the antique valentines and embroidered Chinese coats she collected to her tiny scented bottles from Neal’s Yard Remedies; there had always been something bright and magical about her unknown faraway life….

Near the end of the book, as Theo reflects on everything he’s been through, he says:

And as much as I’d like to believe there’s a truth beyond illusion, I’ve come to believe that there’s no truth beyond illusion. Because, between ‘reality’ on the one hand, and the point where the mind strikes reality, there’s a middle zone, a rainbow edge where beauty comes into being, where two very different surfaces mingle and blur to provide what life does not; and this is the space where all art exists, and all magic.

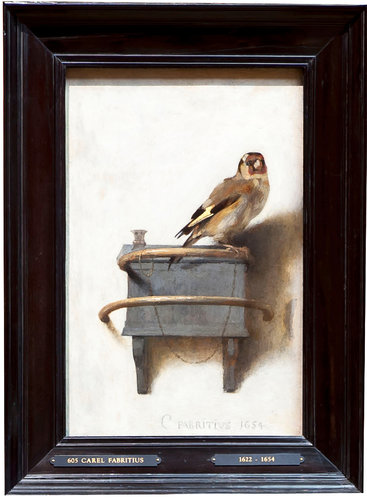

Whether you agree with her/him (Tartt, the author, writing through Theo, the protagonist) or not, you must love their words. Their reflections on truth and reality and beauty and art and magic. The book is full of all those things, which is another reason I love it. The protagonist credits the painting, “The Goldfinch,” with his own personal survival in many ways, praising it and “whatever teaches us to sing ourselves out of despair.”

Dostoyevsky said that beauty will save the world. Theo Decker seems to have embraced that philosophy by what he lived. By what he survived:

Dostoyevsky said that beauty will save the world. Theo Decker seems to have embraced that philosophy by what he lived. By what he survived:

And I add my own love to the history of people who have loved beautiful things, and looked out for them, and pulled them from the fire, and sought them when they were lost, and tried to preserve them and save then while passing them along literally from hand to hand, singing out brilliantly from the wreck of time to the next generation of lovers, and the next.

I was emailing with a close friend who just finished reading The Goldfinch a couple of weeks ago. Like me, she was sad to be finished with it, and also sad that we will probably have to wait another decade for Tartt’s next novel. (Tartt rarely gives interviews, but here’s one you might enjoy. Did you know she’s from Greenwood, Mississippi, and went to school at Ole Miss?) And don’t you love it that the painting is drawing crowds at New York’s Frick Museum since the release of the novel? Another space where art exists….