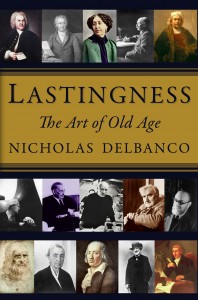

Once again I have come across a book and can’t remember who recommended it to me… perhaps they are reading my blog and will let me know if they suggested Lastingness: The Art of Old Age by award-winning author, Nicholas Delbanco.

Once again I have come across a book and can’t remember who recommended it to me… perhaps they are reading my blog and will let me know if they suggested Lastingness: The Art of Old Age by award-winning author, Nicholas Delbanco.

My interest is in the book is on at least two levels:

Aging is a topic that most baby boomers must be addressing in some way these days. I’m hearing Bonnie Tyler’s voice in my head as I write this:

Every now and then I get a little bit nervous that the best of all the years have gone by.

As our bodies (and for some, our minds) slow down and deliver increasing aches and pains, we want to find ways to take better care of ourselves during what will surely be the final “quarter” for most of us. I’m looking forward to hosting another literary salon on October 28, when my friend and neighbor, Sally Thomason, will lead a group of women in a discussion about her book, The Living Spirit of the Crone: Turning Aging Inside Out.

Side note: Sally turned 80 this year. She came over for coffee yesterday morning and shared some wisdom that helped me with some recent personal struggles. I thought about what a gift she is in my life when I heard Cicely Tyson say recently, “Spend time with your elders while you still have them.”

But beyond aging as a general topic, Delbanco addresses the aging artist—the writer, painter, and musician. Since I’ve already “failed” at my goal of publishing a book before turning 60 (I’m 63) I’m always looking for examples of successful artists over 60. And Delbanco’s book is about “tribal elders in the world of art.” And about what he calls, “lastingness.” And although he also writes about musicians and visual artists, I’m most interested in the spotlight he shines on aging writers. Some of those writers he mentions:

The novelists Penelope Fitzgerald and Harriet Doerr published no creative writing till their sixties; their fictions from the outset were mature. Peter Matthiessen in his eighties earned the National Book Award for revising a trilogy of novels he had published long before; in her ninth decade Doris Lessing received the Nobel Prize for Literature she continues to produce. The final novels of Wallace Stegner and recent books by Alice Munro, Philip Roth, and William Trevor are at least as prepossessing as their early texts.

So, what does the elderly writer need in order to succeed?

For the elderly practitioner, perseverance is, just as much as for the apprentice, a necessary component of the production of art. Continued health, sufficient comfort so that work is not an agony, continued expectation that what you write might be read…. And something else it’s harder to define, that may perhaps be best described as the willingness to stay interested, to pay the kind of alert attention to the world around you that the wide-eyed young routinely pay.

Sufficient comfort so that work is not an agony. For some of us this means taking time to rest and not sit at a computer for hours on end every day, especially if you have hardware in your cervical spine from a broken neck that happened just over a year ago.

Expectation that what you write might be read. I think that’s the most important advice I’ve read in Delbanco’s book so far. Over the past seven years I’ve written and published over a dozen essays, but writing and publishing novels at my age requires another level of perseverance. I’ll try to keep his words in mind as I move forward:

The novel is, by and large, a hopeful genre; full of brass and energy, wit happy resolutions and virtue triumphant and vice defeated. Or if the mode is tragic and the ending sad, the novelist and his or her characters have waged a valiant struggle and lost a goodly fight.

A hopeful genre requires a hopeful practitioner. And so I press on.