Last night I met with a group of writers who gather to critique one another’s manuscripts. The genre and subject matter varies from meeting to meeting, and even within a meeting. One manuscript was a short story (fiction) and the other was a chapter from a memoir (nonfiction). What the two manuscripts had in common was the author’s goal: to tell a story, and to tell it well.

Last night I met with a group of writers who gather to critique one another’s manuscripts. The genre and subject matter varies from meeting to meeting, and even within a meeting. One manuscript was a short story (fiction) and the other was a chapter from a memoir (nonfiction). What the two manuscripts had in common was the author’s goal: to tell a story, and to tell it well.

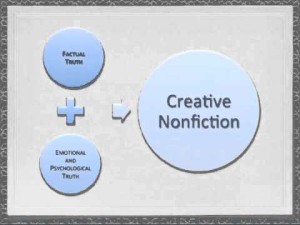

Today I’m only going to comment on the nonfiction piece. And not actually on the piece itself, but on the opportunity it presented for a discussion of genre. Nonfiction can fall into one of many sub-genres, including (but not exhaustively) biography, memoir, essay, narrative history, didactic, legal, and others. And even amongst the subgenres, the style and approach of the author can guide the work into the general category known as creative nonfiction. As Lee Gutkind (affectionately called the “Godfather of Creative Nonfiction” says in this article in the Creative Nonfiction Journal, “What is Creative Nonfiction?”:

The words “creative” and “nonfiction” describe the form. The word “creative” refers to the use of literary craft, the techniques fiction writers, playwrights, and poets employ to present nonfiction—factually accurate prose about real people and events—in a compelling, vivid, dramatic manner. The goal is to make nonfiction stories read like fiction so that your readers are as enthralled by fact as they are by fantasy.

And as Gutkind says in this video, it’s a “combination of style and substance.” Writing a true story using these techniques is a choice the author makes—or doesn’t make—in crafting his memoir, for example. If the intent is to write a historic narrative, journalistic report, or academic paper, one might not choose this approach. But if the author wants to engage the universal reader he might consider using the compelling, vivid tools of the fiction writer. The example I shared at the writing group last night was the technique used by screen writers of disaster movies: they first introduce us to the characters, showing some drama from their personal lives so that we begin to care about them and have a strong emotional response when the disaster hits.

And as Gutkind says in this video, it’s a “combination of style and substance.” Writing a true story using these techniques is a choice the author makes—or doesn’t make—in crafting his memoir, for example. If the intent is to write a historic narrative, journalistic report, or academic paper, one might not choose this approach. But if the author wants to engage the universal reader he might consider using the compelling, vivid tools of the fiction writer. The example I shared at the writing group last night was the technique used by screen writers of disaster movies: they first introduce us to the characters, showing some drama from their personal lives so that we begin to care about them and have a strong emotional response when the disaster hits.

My friend (and fellow contributor to the new anthology, Dumped: Stories of Women Unfriending Women) Jessica Handler did a beautiful job with the craft of creative nonfiction in her memoir of loss and grief, Invisible Sisters (Public Affairs, Perseus Books Group, 2009). She could have written a scientific, medical “report” about the diseases that took her two sisters from her, and it might have been interesting and educational. But we wouldn’t care about her sisters, and about her loss. Instead she shows us the colorful and often harrowing milieu of a family trying to hold together as tragedy pulls it apart. Her father’s work and personal habits. Her parents’ marriage. Her own hopes and fears. It’s all in there, woven together in such a way that the reader couldn’t separate the facts from the feelings even if she wanted to. Here’s a brief image of her father’s growing dysfunction:

My friend (and fellow contributor to the new anthology, Dumped: Stories of Women Unfriending Women) Jessica Handler did a beautiful job with the craft of creative nonfiction in her memoir of loss and grief, Invisible Sisters (Public Affairs, Perseus Books Group, 2009). She could have written a scientific, medical “report” about the diseases that took her two sisters from her, and it might have been interesting and educational. But we wouldn’t care about her sisters, and about her loss. Instead she shows us the colorful and often harrowing milieu of a family trying to hold together as tragedy pulls it apart. Her father’s work and personal habits. Her parents’ marriage. Her own hopes and fears. It’s all in there, woven together in such a way that the reader couldn’t separate the facts from the feelings even if she wanted to. Here’s a brief image of her father’s growing dysfunction:

He made a magpie’s nest of their bed: an ocean-sized California king mattress for which he had the wooden frame specially made. He claimed a bad back, digestive trouble, or a headache. Often he alternated between depression and manic fire, a misery that I knew even then was poorly treated with amphetamines, barbiturates, marijuana and Scotch.

Those few sentences paint a picture of a sick man’s attempt to deal with an unimaginable loss—the deaths of two of his three daughters. Earlier in the book, the author shows us this man’s coat of many colors, including his work on behalf of the underdog in a labor union and his efforts to include his oldest daughter in the important events of the world around their family’s home in Atlanta, even taking her to the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. Her father had moved his Jewish family to the South to participate in the social justice movement of the 1960s, having no idea that the battles he would be fighting under his own roof would overshadow the larger events of society.

Creative nonfiction makes important and sometimes complicated issues and events accessible to the common reader. Jessica’s sisters had diametrically opposed illnesses—Sarah had neutropenia (abnormally low white blood cells) and Susie had leukemia (abnormally high white blood cells). Jessica could have written a purely scientific piece about their illnesses, but it wouldn’t have been nearly as powerful.

The same is true of the way two other creative nonfiction writers—both living in Memphis and heading up the University of Memphis MFA program—chose to tell their stories. Rebecca Skloot, in The Immortal Life of Henritetta Lacks (2010), and her colleague, Kristen Iversen, who wrote the award-winning memoir, Full Body Burden (2013). I probably would never have read either of these books if they had been written in the style of scientific, political, or medical journalism. I learned about these important issues because the authors chose to use the literary tools of creative nonfiction to engage me in the lives of the real characters in their books. They made me care.

Want to learn more about the craft from these authors? Two of them have published books which are used to teach writers how to use these techniques:

Want to learn more about the craft from these authors? Two of them have published books which are used to teach writers how to use these techniques:

Shadow Boxing: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction by Kristen Iversen (2003)

Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Loss by Jessica Handler (2013)

And for more reading about the subgenres of creative nonfiction, read this excellent article by Sue William Silverman: “The Meandering River: An Overview of the Subgenres of Creative Nonfiction.”

Write those stories and tell them true… and make us care.

I really like this post, including the link to “The Meandering River,” and I might get one of the books you suggested at the end! I am trying to revise a longer CNF piece for a journal called The Big Roundtable. Some of the editor’s feedback was that my piece read like personal essay, but I needed to lift it to the level of nonfiction narrative. I feel like I’m still trying to sort out the difference, but I think I need to employ more fiction-type techniques of telling a story and less personal summary or reflection. Show, don’t tell, right? It is all so hard . . . I really think CNF has SO many facets, too, that it’s hard to parse out one type from another sometimes. This post was helpful.

Interesting comment your editor made, Karissa, since personal essay, as a genre, doesn’t need to be “lifted to the level” of narrative nonfiction. They make it sound like one is better than the other when they are just different. I guess they are looking for one kind of piece for their journal or for that issue. Are you okay with making that change in your essay? It’s hard to work to please an editor and hold onto yourself and your own vision for your work sometimes. I’ve been going through that with revisions to my novel, so I know how that feels. Thanks so much for reading and I’m glad the sources I mentioned here were helpful!

I thought it was an interesting comment, too. Stung a little, but it also made me try to do some research on the terminology. I think most of the editors have a journalism background rather than a literary background, and the site features longform nonfiction narratives. (Which I would just call CNF, but whatever.) I told them I’m willing to try. They suggested breaking it into three parts, so I’m working on the first part now, and they said I can send it in part by part and we’ll work on it together. So we’ll see. I’m willing to withdraw my piece if I get uncomfortable, but I’m not there yet. Thanks for the advice!