This is my second post in a series of reflections on the Lenten season, mostly gleaned from the book God For Us: Rediscovering the Meaning of Lent and Easter. If you missed my first post, you can read it here:

This is my second post in a series of reflections on the Lenten season, mostly gleaned from the book God For Us: Rediscovering the Meaning of Lent and Easter. If you missed my first post, you can read it here:

Today’s reflections are from Ronald Rolheiser’s introduction to the book, and from Beth Bevis’ section, “The Feasts and Fasts of Lent.” (Here’s a nice interview with Bevis on Image Journal’s Good Letters.)

Although I always fight against the difficult ascetical struggle that Lent offers those who chose to enter the fray, on some level I do believe that participating in the rhythms of the season can help my soul. Rolheiser explains why:

Seasons of play are sweeter when they follow seasons of work, seasons of consummation are heightened by seasons of longing, and seasons of intimacy grow out of seasons of solitude…. To taste specialness, we must first have a sense of what is ordinary.

I love play, consummation and intimacy, so it’s hard for me to give those things up, even for a brief period of time. I can’t imagine living the life chosen by monastics, where this rhythm seems tipped in favor of the seasons of work, longing and solitude. Bevis reminds us of how the church calendar helps us with our spiritual struggle:

The liturgical calendar, with its cycle of festivals and fasts alternating with seasons of ‘Ordinary Time,’ helps us to remember not only the breadth of Christian teaching but also what it means to be human, both fallen and redeemed by God.

I get that. It’s just that I’m stubbornly attached to pleasures, and I have to be coaxed into this cycle in order to benefit from it. I have to be reminded why it is good for me, and why the sacrifice is worth the effort. Bevis says,

One of the goals of this season is to reveal habits or mindsets that may be preventing us from experiencing true freedom and wholeness.

The second week of Lent was a time of warring with some of those habits for me—especially with food. Several days of fighting against the fast and one day of binging and purging left me in a messy battle with forgiveness. Those of us with eating disorders aren’t “excused” from participating in spiritual disciplines such as fasting, but we bring our own baggage to the table. We are always hungry and thirsty for something that seems to be just beyond our reach. Bevis reminded me that Lent isn’t a time of spiritual dryness:

There can be as much meaning in a strategically instituted silence as there is in a resounding ‘alleluia,’ as much to glean from a spare Lenten meal as from an Easter feast.

But it’s Rolheiser who explains how we use food (and other pleasures) to keep from dealing with the issues that plague our souls, which he calls “the chaos inside of us”:

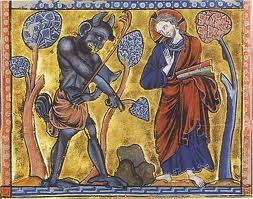

Our paranoia, our anger, our jealousies, our distance from others, our fantasies, our grandiosity, our addictions, our unresolved hurts, our sexual complexity, our incapacity to really pray, our faith doubts, and our dark secrets. The normal ‘food’ that we eat (distractions, busyness, entertainment, ordinary life) works to shield us from the deeper chaos that lurks beneath the surface of our lives. Lent invites us to stop eating, so to speak, whatever protects us from having to face the desert that is inside of us. It invites us to feel our smallness, to feel our vulnerability to feel our fears, and to open ourselves to the chaos of the desert so that we and finally give the angels a chance to feed us.

He’s referring to the way the angels fed Jesus during his forty days of fasting in the desert. I think we can only experience the presence of angels in our lives if we leave room for them in our longing. In our hunger and thirst.

But how can we make it for forty days without feeding that hunger and thirst? The Church provides “mini-feasts” for us every Sunday, as Bevis says:

In the liturgical calendar, the church sees Sunday as a weekly microcosm of Easter—a day for celebrating the Resurrection…. But in addition to the theological reasons for the Sunday reprieve, the church recognizes the practical human need for sustenance and encouragement in the midst of Lent. Sundays keep us from falling into a rut of fasting simply for the sake of self-denial; they remind us that the purpose of Lent is to prepare us to receive reconciliation and new life. The Lenten fast is always directed toward that promise of fulfillment, the promise that our hunger will be satisfied.