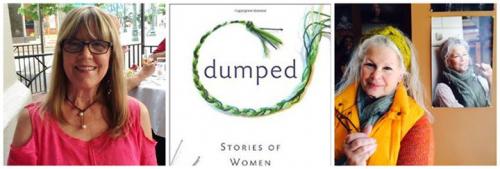

About a month ago I shared a few excerpts from the anthology I was recently published in—Dumped: Stories of Women Unfriending Women. As I’m preparing to go out on a “Southern book tour” (here’s the schedule) with the editor, Nina Gaby (from Vermont) this week and next, I’m taking a closer look at the etiology of the essays in this collection. But this time I’m not looking at these pieces with my writer/editor hat on. I’m looking at them from the reader’s point of view, especially the woman reader, whom I assume will be our target audience. Since I only know three of the other contributors personally, I can read most of the essays without bias, the way most of our readers will read them. And hopefully I can feel what they are feeling.

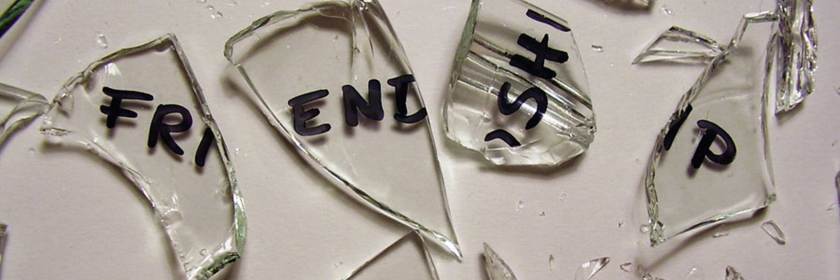

Two of my closest friends have read the book. One told me that at first she wished I had been more explicit in describing the pain I have experienced in the loss of the friend of whom I write. But then, after reading the other essays in the book, she said she was glad mine was a little more upbeat. The other friend felt that many of the essays were “depressing” or overly “bitchy.” I think what both of them were experiencing was the rawness of the pain and hurt experienced by the authors. Being dumped by a close friend really does a number on the psyche.

Nina Gaby is a psychiatric nurse practitioner. She’s spent a lifetime helping others deal with their pain, so she knows of what she speaks when she writes of her own experience as the person being hurt by another, first at age thirteen and later at fifty:

I had to pretend it didn’t matter. I learned to project a safer perspective onto a wall between me and the pain. It made me independent with a never-quite-fulfilled craving for closeness. Maybe that was part of the problem. The resultant sheer avoidance never made it any easier, not at thirteen, not at fifty.

That “never-quite-fulfilled craving for closeness” is something I have felt my whole life. And I do think it is similar—if not exactly the same—as the pain one experiences when childhood abuse happens. As Robert Goolrich writes in his excellent memoir, The End of the World as We Know It,:

If you don’t receive love from the ones who are meant to love you, you will never stop looking for it, like an amputee who never stops missing his leg, like the ex-smoker who wants a cigarette after lunch fifteen years later. It sounds trite. It’s true.

You will look for it in objects that you buy without want. You will look for it in faces you do not desire. You will look for it in expensive hotel rooms, in the careful attentiveness of the men and women who change the sheets every day, who bring you pots of tea and thinly sliced lemon and treat you with false deference….You will look for it in shopgirls and the kind of sad and splendid men who sell you clothing You will look for it. And you will never find it. You will not find a trace….

I tell it for the fathers The priests. The football coaches…. I tell it because there is an ache in my heart for the imagined beauty of a life I haven’t had, from which I have been locked out, and it never goes away.

(You can read my blog post about his reading at Square Books in Oxford back in 2010 if you’re interested.)

That ache in his heart that never goes away. That looking for love in places you’ll never find it. I know that ache, and I believe the women who contributed essays to this anthology know that ache. So, if we never “get over it,” how do we deal with it in a healthy way?

One of the contributors, Mary Ann Noe, closes her essay with these words:

I thought I’d get over it. It still surfaces on some mornings when the air is just so and I sling a sweatshirt around my shoulders…. When someone tries to finish my sentence and doesn’t get it right. Those memories bring up sepia-toned images, nothing more. But when I come across that photo of the two of us, I’m still blindsided. I wonder what I did. Or maybe what I didn’t do? I know one thing: I’ll never figure it out. And I realize I don’t have to.

Mary Ann has learned that she doesn’t have to figure it out. Maybe we don’t need that kind of closure to move on from the hurt of being dumped by someone we love. The person I wrote about in my essay was only fifteen, as was I, when she ended our friendship. And because we live and move in different circles (and cities) I can choose to just not think about her any more. That works most of the time. But there’s another friend—one I didn’t write about in the anthology—who hurt me as an adult. And although she made an effort to reconcile at one point (albeit on her terms) I kept my boundaries up, not being willing to completely entrust my heart to her again. We see each other rarely, every couple of years, at an event where we have shared friends, and I’m okay with things the way they are. She and I have both suffered lots of pain in our lives, and maybe this is just the best we can do. As Alexis Paige, another contributor to Dumped, writes:

With girlfriends, I didn’t know how to work through their or my own ugliness, how to fight for the friendship. I left because it was easier.

Alexis owns her part in the loss, as we probably all should do if we’re honest, because we are all broken human beings, who “become alienated from other women, just as you are alienated from yourself.” (Again Alexis’ words.)

We are alienated from ourselves because we are fallen creatures. God created us to be one with ourselves. That’s good mental health. When we are at war with ourselves, we are mentally ill, which is our state much of the time.

I think my “take home” from the book is to continue to work to heal my own inner brokenness in order to be able to have healthier friendships. As Alexis says, to work through my own ugliness. Here’s to healthier insides!

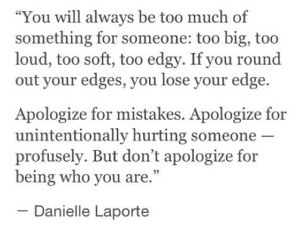

P. S. While searching for images to include with this post, I came across this quote by Danielle Laporte and thought it was applicable to the discussion here. Sometimes it’s hard to be in a friendship and still hold onto yourself.

P. S. While searching for images to include with this post, I came across this quote by Danielle Laporte and thought it was applicable to the discussion here. Sometimes it’s hard to be in a friendship and still hold onto yourself.

“We are alienated from ourselves because we are fallen creatures. God created us to be one with ourselves. That’s good mental health. When we are at war with ourselves, we are mentally ill, which is our state much of the time.”

Great quote. Also, for depression and bi-polar, God has provided doctors and nurses to help,and for the hardest cases, medications that might (not always, at all times) help us to be one with ourselves.

Susan, I think you are fortunate to have 2 friends with two different points of view. And maybe you are fortunate to be able to process them equally… Perhaps that is part of true mental health…

Thanks, Melody. It’s interesting that those two friends are from two different times in my life… one from my childhood and adolescence, and the other from my middle-age adult years. Love them both so much. And their support of me is so wonderful. I hear you about the bi-polar (I know some folks who struggle with this) and depression (one of my demons) and yes, doctors and meds can help. Looking forward to meeting you at the reading in New York City in a few weeks!

Thank you so much, Susan. You have touched me…and soothed some aching.

I’m so glad, Diana. Sometimes just reading other people’s stories can be powerful. Thanks, always, for reading.