What comes to mind when you think of the first two weeks of August?

What comes to mind when you think of the first two weeks of August?

Last days of summer vacation? Final trip to the beach? Swim team wrapping up another season? One more summer camp session? Last opportunities for backyard cookouts? Little league all star games?

Preparations for back-to-school? Shopping for new clothes, shoes, and school supplies? Wondering which classes you would be in and which friends you would be with? Would your summer romance survive the changes that come with a new school year, or would someone more exciting come along? Football or cheerleading two-a-days in the early mornings and late afternoons?

When I was growing up in Jackson, Mississippi, everything seemed to slow down during August. It was hot. Sometimes we referred to those days as the “dog days of summer.” The only places that were comfortable were the swimming pool at Colonial Country Club (where my father and brother played golf and I swam and played bridge) and the central air-conditioning in the home my parents built in the late ‘50s. There were no shopping malls yet. Bowling alleys and drug store lunch counters were about all we had for indoor gathering spots to escape the heat. The joys of summer were fading, and we began to look forward to returning to school after Labor Day.

There were no significant holidays on the calendar between the Fourth of July and Labor Day. Nothing to mark the passing of time during what often seemed like the longest month of the year.

Contrast that with the calendar of the Orthodox Church. While its advent mirrors the typical school schedule—September 1 being the first day of the Orthodox Church year—and it offers holidays at Christmas and Easter (known as Pascha in the Orthodox Church) which are familiar to most Americans, that’s where the similarity ends. It’s the Orthodox schedule of fasting and feasting that throws a curve ball at our traditional American pastimes.

The biggest curve ball it throws is the Nativity Fast. Forty days before Christmas—when the rest of the world is having parties and enjoying special holidays foods—the Orthodox Church observes a fast from many foods and festivities, in preparation of the celebration of Christmas. It’s often difficult to navigate the plethora of office and neighborhood parties and school activities that aren’t in keeping with the fast. But at least the Orthodox Church breaks that fast with a celebration that begins with Christmas and continues for twelve days—through Theophany. But even after twenty five years as a convert to Orthodox Christianity, I still struggle with this fast.

Truth is, I struggle with the whole concept of fasting. It’s not that I don’t understand what spiritual benefits can come from this ascetic practice. It’s just that I have a hard time embracing self-denial and obedience to what sometimes feels like rules rather than guildelines.

Father Stephen Freeman, an Orthodox priest in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, says this about “Why We Fast”: (Click on the link to read more—it’s an excellent article.)

“Fasting is not dieting. Fasting is not about keeping a Christian version of kosher. Fasting is about hunger and humility (which is increased as we allow ourselves to become weak). Fasting is about allowing our heart to break.”

And Douglas Cramer addresses the issue from a different tact, in his article, “A Culture Obsessed With Food”: (Again, click the link for the complete article.)

“The whole purpose of fasting, of spiritual athleticism, is to bring ourselves back to God. To bring our attention back where it belongs. Stop obsessing about food: fast, and draw closer to God. Stop obsessing about money: give alms, and draw closer to God. Stop obsessing about time: go to church for worship, and draw closer to God.”

So, what does all this have to do with the first two weeks of August?

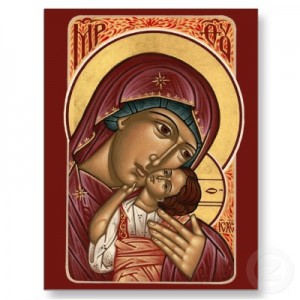

August 1-14 is designated by the Orthodox Church as the “Dormition Fast.” It’s a time when Orthodox Christians fast (from meat, dairy, fish, and wine most days) and pray and prepare to celebrate the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God on August 15. (Dormition means “falling asleep”)

Daniel Manzuk says, in his article, “Why A Fast for Dormition:”

“So why do we fast before Dormition? In a close-knit family, word that its matriarch is on her deathbed brings normal life to a halt. Otherwise important things (parties, TV, luxuries, personal desires) become unimportant; life comes to revolve around the dying matriarch. It is the same with the Orthodox family; word that our matriarch is on her deathbed, could not (or at least should not) have any different effect than the one just mentioned. The Church, through the Paraklesis Service, gives us the opportunity to come to that deathbed and eulogize and entreat the woman who bore God, the vessel of our salvation and our chief advocate at His divine throne. And as, in the earthly family, daily routines and the indulgence in personal wants should come to a halt. Fasting, in its full sense (abstaining from food and desires) accomplishes this.”

(You can listen to a podcast by Frederica Mathewes-Green: “Tender Love and the Dormition.”)

These words are something I can sink my teeth into (in lieu of sinking them into a nice grilled tenderloin) as I muddle through these difficult traditions. The Mother of God has a special place in my heart, and if fasting can help me obtain a heightened awareness of her presence in my life, I’m willing to try. But I’m not willing to be legalistic with my efforts. If I’m going to enter into this fast it needs to be more about what I will do than what I will not do (or eat). Fasting without prayer and alms is fruitless. So, with God’s help, I will pray more. Including attending some of the Paraklesis services, which are prayed at my parish on Monday, Wednesday and Friday evenings during the Dormition Fast. That’s tonight. And maybe, when I smell the delicious aromas of summer on my neighbors’ grills, I will think of those who are without food, (or water or air-conditioning) and find a way to reach out to them. It might be time for another bottled-water delivery. And time to re-double my prayers to the Mother of God on behalf of my neighbors who are homeless, hungry, or hot. Those who don’t have jobs and food, much less swimming pools or air-conditioning.

O Mother of the God of Love, have mercy and compassion upon us all.