Wisdom from YOK

Twelve years ago I attended my first (of seven) Yoknapatawpha Summer Writers Workshops in Oxford, Mississippi. I wrote about it on my old blog, here: “Learning to See and Write Sunsets,” on June 9, 2008. Over the years that I participated in the YOK Shop (the name has changed), many chapters of my works-in-progress were critiqued by the faculty and my fellow participants, which was invaluable. (CLICK HERE for a post with links to posts about most of the workshops.) And the “craft talks” at each workshop were also an important part of this “mini MFA” experience. One of those came to mind yesterday, when I discovered an old manuscript that I had put aside because of the “watchers at the gates.”

Who are the Watchers?

At the 2008 workshop, one of the presenters, Mississippi author Jere Hoar, talked about something that often happens to writers. The concept wasn’t original with him, and he gave credit first to the writer Gail Godwin and her essay, “The Watcher at the Gate.” And her source, the German writer Friedrich Schiller, who warned writers not to let their creative power get stolen by the watchers at the gates:

“In isolation, an idea may be quite insignificant, and venturesome in the extreme, but it may acquire importance from an idea which follows it. . . . In the case of a creative mind, it seems to me, the intellect has withdrawn its watchers from the gates, and the ideas rush in pell-mell, and only then does it review and inspect the multitude. You are ashamed or afraid of the momentary and passing madness which is found in all real creators, the longer or shorter duration of which distinguishes the thinking artist from the dreamer. . . . You reject too soon and discriminate too severely.” (bold emphasis mine)

Six Years Later

At the 2014 YOK Shop—the last one I attended—I submitted the opening chapter of a new novel to be critiqued. Unlike all my previous writing, this new book was free from any agendas. It was not based on or influenced by any of my personal demons or experiences. It was about art. And it had a bit of mystery to it. A real departure for me, but it felt alive and exciting.

My mentor during all those years at YOK, the author Scott Morris, said this about the chapter I submitted: (This is an excerpt from a longer page of comments.)

I think this is a very interesting idea for a novel, and this chapter is very well executed. Your writing is so polished and professional—you make it seem really easy, though I know you’ve worked hard to get to this high level.

My creative ego was stroked and I was excited about the work. Most of the comments from the other participants in my workshop group were fairly positive, and I returned home ready to continue drafting this novel. Until I decided to share it with other writers. That’s when I allowed them to become “watchers” and I felt, like Schiller described, “ashamed or afraid of the momentary and passing madness which is found in all real creators….” The creative ideas, which had (again using Schiller’s words) “rushed in pell-mell,” were squashed. In this particular case, it wasn’t my interior “watchers” but these exterior ones—my fellow writers—who “rejected too soon and discriminated too severely.” I put the manuscript away. For six years.

While I’m Waiting

At the beginning of this week I looked at my calendar and panicked. So little there. I am so motivated by deadlines and events and projects. I found myself in a holding pattern. I’m finished with early revisions on the new novel John and Elizabeth until I hear back from one more important beta reader. And last week I sent my personal essay collection Pilgrim Interrupted out to another publisher after another round of revisions. And so now I wait. Which drives me crazy. Oh, sure, I need to clean out my closet and do some filing in my office. I need to organize all the junk on my bathroom counter. And now that I have time, I could do another watercolor using a kit my children gave me. But when I’m not writing, I feel restless. What to do?

A Hidden Treasure?

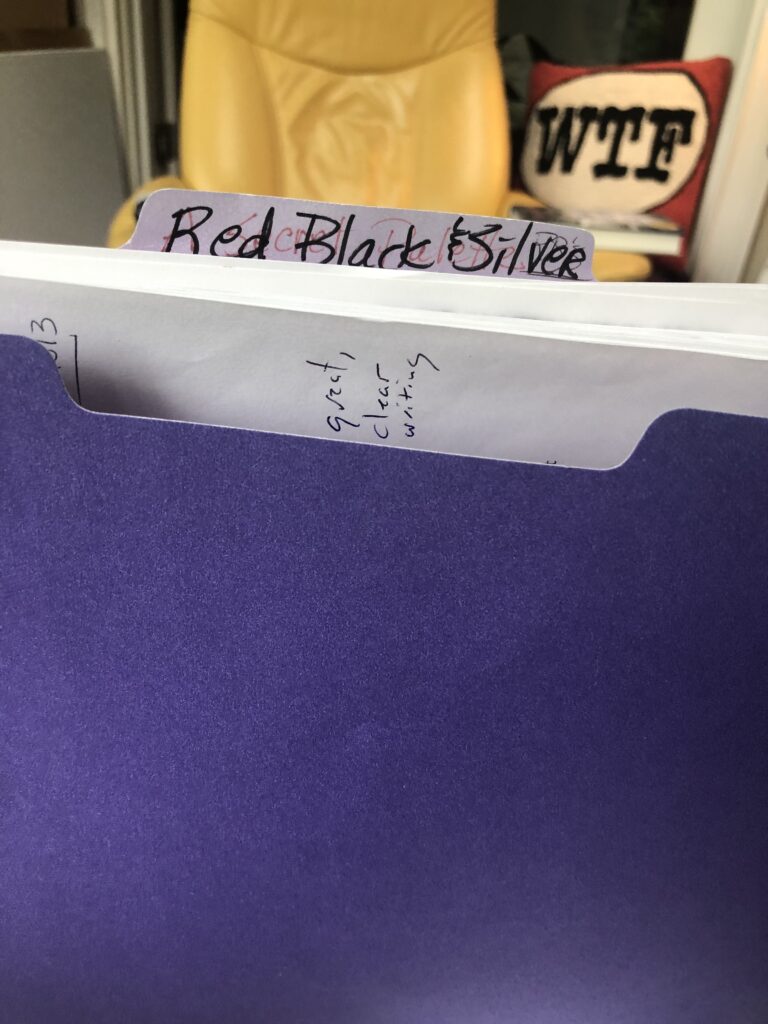

For some reason yesterday I found myself pulling out a large purple file folder that I hadn’t opened since 2014. The one with the first chapter of a new novel (working title is Red, Black, and Silver, the name of the last painting Jackson Pollock did before he died) inside, along with critiques from the last YOK Shop and also from other writers. I opened the cover slowly, and the first thing I saw was Scott’s critique. And then I read the chapter. I won’t say I’m in love with it, but I do think it’s worth pursuing. Whether or not I finish it, the work of continuing the process will be good for my soul. I’ve always been product-oriented rather than process-oriented, but I think now it’s time to see where the process leads me. Or, maybe where Esther (the protagonist) leads me. I will leave you with an excerpt from the synopsis:

Esther’s role in the story is to bring to light the layers of human desire that were hidden . . . for many decades. . . . “Esther” means “hidden” in Hebrew.

Susan, what an beautifully related and enjoyable account of your writing journey and it’s intriguing to know where you are at this time and where it might take you. The final sentence intrigues as my given birth name was Esther Sarah, but I was always called Sally, so when I married I claimed that as my legal name so that all my official documents would adhere to the name I lived by.

However, it did give me a bit of a pause as the first daughter in my mother’s ancestry had been called Esther for five or six generations, and it was her name.

When, as a child, I looked up my names meaning, Esther meant “star” (not “hidden” but who knows) and Sarah meant “princess”. Although no one ever called me by Esther Sarah (except when my daddy was angry about something), as an eight year old, I felt “star princess” was a pretty cool idenity. Can’t wait to see how your Esther develops

Thanks, Sally. And yes, I also saw that Esther means, “star,” but for my purposes I’m using it’s other meaning, “hidden.” We’ll see how/if this book turns out!