During my wonderful “birthday weekend” in Little Rock, one of my favorite outings was my visit to the Little Rock library’s annual book sale. I went with my friend, Daphne, and her 16-year-old son, Simon. As we entered the bowels of the building, we split up and explored the various shelves and tables. Having recently purchased about 6 books at Sundog Books in Seaside, Florida, I really wasn’t planning on buying anything. Right.

During my wonderful “birthday weekend” in Little Rock, one of my favorite outings was my visit to the Little Rock library’s annual book sale. I went with my friend, Daphne, and her 16-year-old son, Simon. As we entered the bowels of the building, we split up and explored the various shelves and tables. Having recently purchased about 6 books at Sundog Books in Seaside, Florida, I really wasn’t planning on buying anything. Right.

But I did, indeed, find treasures—four books for a grand total of $3.50. And all four of them I could “justify” as legitimate research for my current work-in-progress, The Secret Book Club. Well, at least three of them. Especially this wonderful little volume of interviews with women writers, Women Writers Talking, edited by Janet Todd. My joy at finding this book (for 50 cents) was that two of the women interviewed are Erica Jong and Marilyn French—both authors whose books are chosen by the women in the 1970s book club that I’m creating.

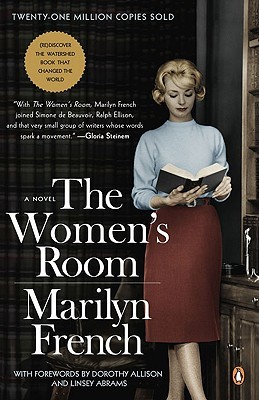

I’m about half way through reading French’s novel, The Women’s Room, so I read her interview first. Several things caught my interest. First of all, one of the strengths of The Women’s Room, in my opinion, is how she reveals the universality of women’s feelings about the social mores of the 1950s,’60s and ’70s. In the interview she gave with Janet Todd, she explains why that was so important:

I’m about half way through reading French’s novel, The Women’s Room, so I read her interview first. Several things caught my interest. First of all, one of the strengths of The Women’s Room, in my opinion, is how she reveals the universality of women’s feelings about the social mores of the 1950s,’60s and ’70s. In the interview she gave with Janet Todd, she explains why that was so important:

We live in a culture in which emotion is really looked down on…. If a work of art deals with human emotion as we feel it… it’s going to be called sentimental…. I have a serious respect for emotion.

Talking about her novel, The Women’s Room, French said:

I do think emotion is more accessible to women than men. They’re more aware of it. When men start to feel something, they immediately turn on the TV set and watch a ball game, go out and argue at a political meeting, get rid of their emotions there so they don’t have to be aware they have them. I don’t think men are less emotional than women. I think they’re simply less aware of their emotion, and, when it does come out, it comes out in a very childish way—fourteen-year-old temper tantrums, or five-year-old jealousies. I think women are terribly emotional. Emotion is as much a part of one’s self as mind or body.

Amen. One of my struggles with the Orthodox faith which I converted to in the 1980s is the Church’s approach to emotion. And passion. The Church fathers encourage dispassion, and tend to have a low regard for emotions. And while I won’t go as far as French is saying that “the men of our age are all so hollow and mechanical, emotional zombies,” I do share her frustration with their inaccessibility at times.

French was criticized for being too polemical, and also for overuse of extraneous details, which caused her characters to become exemplars rather than living people. She refuted both criticisms in the interview, and I love both responses:

To the first she replied,

I don’t think the detail is ever extraneous…. I think that is how you create the texture of the day, a life, or an event. I don’t think you do it by describing it in large historical terms. It seems to me that is the very technique of poetry.

Create the texture of the day. Virginia Woolf immediately comes to mind. And Michael Cunningham. And in a different way, Pat Conroy. My favorite writers are masters at creating texture.

To the second criticism, about being too polemic, she replied:

When you’re working against a current, against the very basic assumptions of the culture, if you don’t get polemical, if you don’t say what you have to say, no one is going to hear you.

I feel my courage rising as I read these words and continue reading French’s iconic novel. I’ll share one more excerpt from the interview—one that surprised me:

The one writer who means more to me than any other writer—and always has from the very first time I ever wrote a book a lot of years ago—was Dostoevsky. I recently reread The Brothers Karamazov and found he was writing on the other side of the same question I’m writing about. He’s talking about patriarchy, he’s talking about what does God mean and if a thing called God exists, why. And that huge district attorney’s summing-up of the case against Mitya is essentially a defense of a primal being which is masculine, narrow-minded, insists on certain sexual and moral codes, and so forth. I never though of that as polemical.

Marilyn French and Dostoevsky—two sides to the same question. Fascinating.

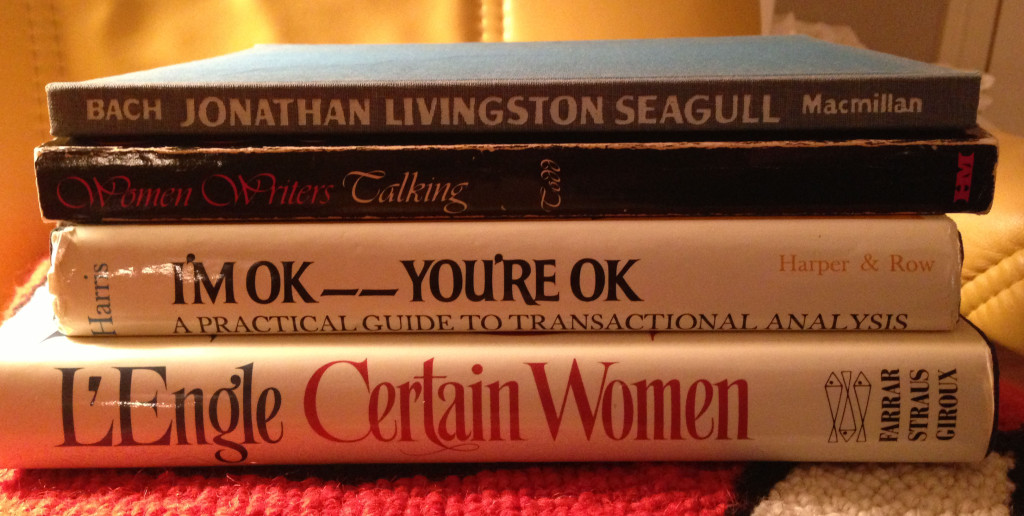

So, as Daphne, Simon and I returned home from the library with our treasures, we spread them out on the coffee table and discussed our choices. Simon chose some wonderful classics from Shakespeare and some excellent volumes of poetry. Daphne scooped up some beautiful picture books for her nieces and nephews. In addition to the volume of interviews with women writers, I came away with Richard Bach’s Jonathan Livingston Seagull (complete with beautiful black and white photographic images), I’m OK—You’re OK (Thomas Harris’ guide to transactional analysis), and Madeleine L’Engle’s 1992 novel, Certain Women. Daphne asked us to describe our experience when we walked into the basement of the library and saw all those books. (A typical Daphne question, God love her.) What were we thinking or feeling?

Simon: I’m gonna get some books.

Susan: It’s musty down here. I wonder if there’s mold on the books. How long can I stay down here? (I’m claustrophobic and a bit OCD.) But then I got lost in the treasures and forgot my fears.

What I would have been thinking, had I already read Marilyn French’s interview, was how many hundreds of writers labored endlessly to create those books, and especially about the brilliance of the ones who knew how to create the texture of a day. A life. An event.