About a year ago, I did a post about literary and commercial fiction. I continue to think about these categories, especially as I work on revisions of my novel. Why? Because some of the conceptions I’ve had in the past about literary fiction hang around my subconscious as I work –with help from a talented editor—to pull my story up to higher standards. But what are those standards?

About a year ago, I did a post about literary and commercial fiction. I continue to think about these categories, especially as I work on revisions of my novel. Why? Because some of the conceptions I’ve had in the past about literary fiction hang around my subconscious as I work –with help from a talented editor—to pull my story up to higher standards. But what are those standards?

Jack Smith, author of Write and Revise for Publication (Writer’s Digest Books, July 2013) wrote an excellent article for the November/December issue of Writer’s Digest on “Understanding the Elements of Literary Fiction.” If you’re writing fiction you should get the magazine and read the complete article. I’m just going to touch on a few of his main points briefly here, so I can get back to work on my novel!

Jack Smith, author of Write and Revise for Publication (Writer’s Digest Books, July 2013) wrote an excellent article for the November/December issue of Writer’s Digest on “Understanding the Elements of Literary Fiction.” If you’re writing fiction you should get the magazine and read the complete article. I’m just going to touch on a few of his main points briefly here, so I can get back to work on my novel!

I always thought one hallmark of literary fiction was flowery language. Smith talks about language in terms of avoiding sentimentality without losing the emotional connection that authors want with their readers. How?

Descriptive literary language doesn’t have to be florid. Rather, it escapes purple prose with the use of apt similes, metaphors and analogies for states of being, actions, thoughts and emotions…. Such language can suggest abstract and universal ideas, which can contribute greatly to thematic development and levels of meaning in a work.

Those “levels of meaning” are crucial to the success of a literary fiction project. How do we achieve that? One way is through symbolism.

Now we move to the real core dividing line between literary and genre fiction: the fact that literary works transcend the surface levels of plot, character and setting. Literary fiction must allow for, or lend itself to, interpretation of human experience, establishing a visions (if not a particular worldview) of what it means to be human.

He goes on to give concrete examples and suggests the author consider such topics as psychology, history, sociology, philosophy, religion and ethics as the framework of our writing.

Since my novel has 3-4 significant characters, the next section of Smith’s article was of particular interest to me—point of view and character:

To make larger insights possible, you must choose the point-of-view character that allows for the greatest capacity to introduce several levels of meaning.

Citing examples from the works of Mark Twain, Henry James, and Herman Melville, Smith shows us several options for achieving these levels of meaning in our stories. In the end, we must raise the bar:

While the literal level of the story or novel is important, successful literary fiction hinges on whether there is more at hand, meaning-wise, than what appears on the surface.

Again, these are just a few “teasers”…. Read the article to get the tools you need to write or revise your work and help it become great literary fiction.

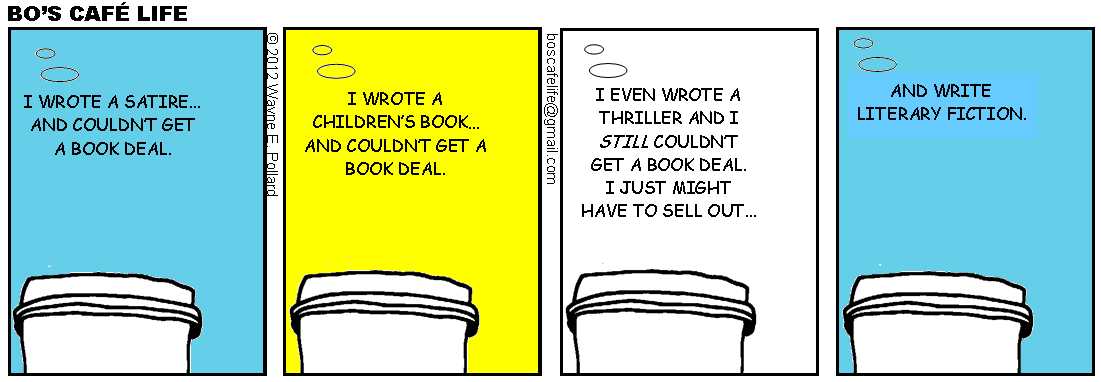

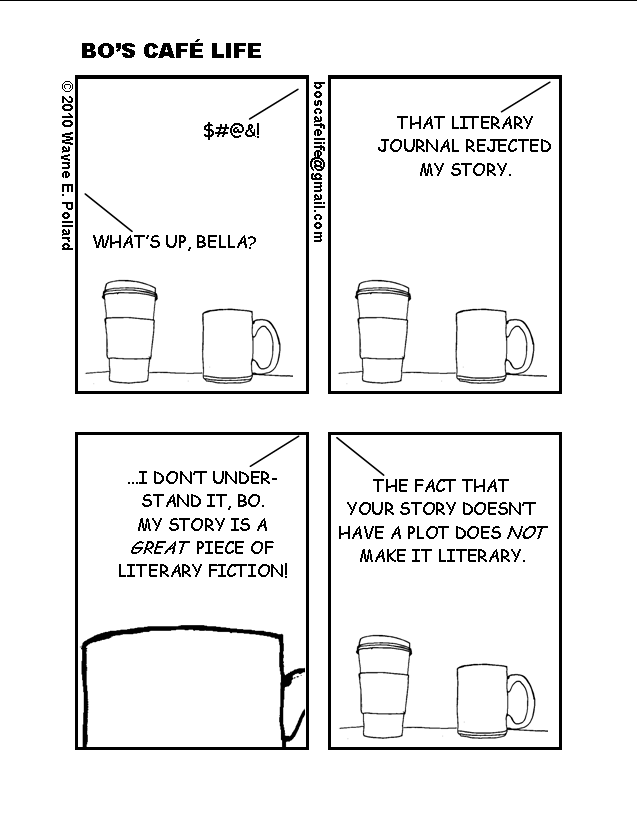

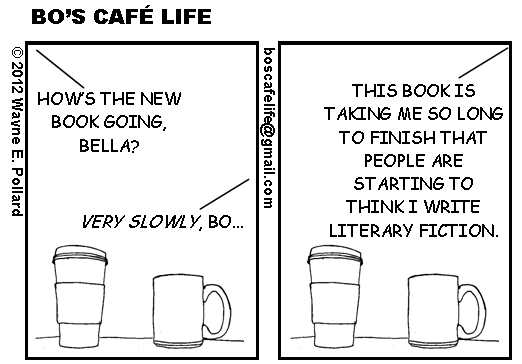

Meanwhile, enjoy these great cartoons from Bo’s Cafe Life!

great piece,

Thanks, Doug. Glad you found it helpful. I’ve just ordered his book.

thank you Susan, good advice from someone who is smack dab in the middle of all this. Write on……

Yes, it was good timing reading this right now, Emma. The revisions are difficult… but I’m pressing on:-) Thanks, always, for reading and commenting.