After two failed attempts at writing my personal/spiritual memoir—the last manuscript was completed in 2010—this week I decided it’s time to try again. It’s not that my earlier attempts were awful. But I wasn’t ready to let go of agendas and bitterness. And as Dani Shapiro says (see source below), “A writer with an agenda is no longer trustworthy. She becomes an unreliable narrator of her own life.”

This time I think I’m ready. I’ve already put together an outline with potential chapter titles, and I’ve drafted a few beginning pages. For now the working title is the same as the one I chose six years ago: Jesus Freaks, Belly Dancers and Nuns.

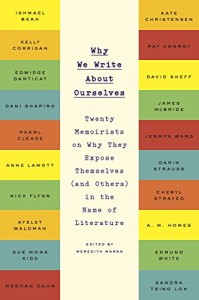

Part of my preparation for beginning this work again has been reading a wonderful new collection of essays, Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature, edited by Meredith Maran. Reading about the experiences and taking to heart the advice of such authors as Pat Conroy, Anne Lamott, Sue Monk Kidd, Jesmyn Ward, Cheryl Strayed, Kate Christensen and Dani Shapiro has only confirmed my feeling that this project is the right “next thing” for me. Several of these authors have echoed what I’ve learned (and blogged about) in the past about the importance of writing memoir as art and not as confessional. (For more on that, see my post in Writer’s Digest from 2011, here.) While it might be therapeutic, that’s not its purpose. As Dani Shapiro Says:

Part of my preparation for beginning this work again has been reading a wonderful new collection of essays, Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature, edited by Meredith Maran. Reading about the experiences and taking to heart the advice of such authors as Pat Conroy, Anne Lamott, Sue Monk Kidd, Jesmyn Ward, Cheryl Strayed, Kate Christensen and Dani Shapiro has only confirmed my feeling that this project is the right “next thing” for me. Several of these authors have echoed what I’ve learned (and blogged about) in the past about the importance of writing memoir as art and not as confessional. (For more on that, see my post in Writer’s Digest from 2011, here.) While it might be therapeutic, that’s not its purpose. As Dani Shapiro Says:

I’m not a believer in memoir as catharsis. It’s a misapprehension that readers have that by writing memoir you’re purging yourself of your demons. Writing memoir has the opposite effect. It embeds your story deep inside you. It mediates the relationship between the present and the past by freezing a moment in time.

I think I experienced that in both of my earlier attempts at memoir, and also in several personal essays I’ve written and had published. So what’s the purpose of memoir, then, according to Shapiro?

One of the greatest gifts of writing memoir is having a way to shape that chaos, looking at all the pieces side by side so they make more sense. It’s a supreme act of control to understand a life as a story that resonates with others. It’s not a diary. It’s taking this chaos and making a story out of it, attempting to make art out of it.

A supreme act of control. How do we do that? Kate Christensen’s essay contains this advice:

I was creating a voice, an “I”—as well as practicing a writerly detachment from emotion—an ability to record and relay extreme states in dispassionate, clean prose.

But practicing writerly detachment and controlling our emotions as we make art from our lives doesn’t mean glossing over the hard stuff. As Jesmyn Ward says:

You get the most powerful material when you write toward whatever hurts. Don’t avoid it. Don’t run from it. Don’t write toward what’s easy. We recognize our humanity in those most difficult moments that people share.

I’ll close with a quote from Cheryl Strayed’s essay in the collection, because she speaks to the fears I struggle with as I begin this work, and to the reason I begin it in spite of those fears:

I’ll close with a quote from Cheryl Strayed’s essay in the collection, because she speaks to the fears I struggle with as I begin this work, and to the reason I begin it in spite of those fears:

I don’t feel inhibited when I’m really working. When I’m working I’m split open and fearless. I feel inhibited when I spin my wheels wondering what others will think of my work. I’m fueled by the desire to give beauty and truth to the world via the sentences I construct. I really want that in this deep, core, essential way. There’s an ache inside me that’s soothed only by writing.

Amen. And so it begins….

P.S. Watch this fun interview with editor Meredith Maran and several of the contributing authors to Why We Write About Ourselves.