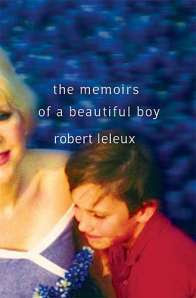

I met Robert Leleux in January of 2010 at the 2010 Pulpwood Queens’ Girlfriend Weekend in Jefferson, Texas. Along with the Pulpwood Queens’ fearless leader, Kathy Patrick, Robert was MC for the weekend, filled with dozens of amazing authors and several hundred members of Pulpwood Queens book clubs nationwide. I was struck by Robert’s warm and compassion when I met him, as well as his humor and joy. And now I understand more about what’s behind this “Beautiful Boy.”

The Living End: A Memoir of Forgetting and Forgiving is Robert’s latest book, and it’s even more powerful than his first. Or maybe it struck me that way because the subject matter hit so close to home—it’s about the broken relationship between his mother and his grandmother, and how Alzheimer’s (his grandmother’s) healed the breach. If you read my blog regularly, you know that this is also true in my relationship with my 84-year-old mother, who also has Alzheimer’s. And yes, I’ve written a dozen or more essays about Mother’s decline (one of them, “The Glasses,” is published in Volume 2, Issue 2 of the Southern Women’s Review) but after reading Robert’s exquisite memoir, I realize he has said everything I want to say, and he has said it brilliantly.

close to home—it’s about the broken relationship between his mother and his grandmother, and how Alzheimer’s (his grandmother’s) healed the breach. If you read my blog regularly, you know that this is also true in my relationship with my 84-year-old mother, who also has Alzheimer’s. And yes, I’ve written a dozen or more essays about Mother’s decline (one of them, “The Glasses,” is published in Volume 2, Issue 2 of the Southern Women’s Review) but after reading Robert’s exquisite memoir, I realize he has said everything I want to say, and he has said it brilliantly.

It doesn’t hurt that his mother and grandmother are a bit more, well, colorful, than mine. When Robert hadn’t seen his grandmother for ten years due to her abandonment of his mother, he called her (JoAnn) in a time of crisis, and here’s what she said:

“Well, hasn’t your life just gone from quail eggs on toast to shit on a shovel?”

That’s just a sneak preview of how colorful JoAnn is. And Robert’s mother? When he describes the dissolution of his family life, he said:

“This dissolution included Mother taking to drink. (We’re Irish.) And it also included Mother shaving her head, and then Krazy Gluing plastic hair to her bald scalp.”

And she’s not the one with Alzheimer’s!

Later in the book, when Robert convinced his mother to meet with his grandmother for the first time in almost forty years, he describes their initial meeting this way:

“It was as though her light was refracted through Alzheimer’s, blazing through the cracks of her infirmity. That night, JoAnn might have forgotten the information of her life, her biographical data, but she seemed to remember who she was. From her thronelike chair, she aimed all her star quality, all her twinkling, undulating charm, directly at my mother. She beamed and petted and doted upon her daughter, my mother, who seemed flustered and ruffled, thrown off balance by her mother’s courtship.”

I remember clearly the turning point with my own mother in this regard. I was visiting her in the nursing home a couple of years ago and she kept complimenting everything about me—my hair, my clothes, everything I did. She kept telling everyone around us at the nursing home, “This is my daughter. Isn’t she beautiful? She’s the best daughter in the world!” Coming from someone who only told me I was fat or my hair was wrong for most of my life, this was at first a bit off-putting. But once I got used to it, it was redemptive. She even complimented the coloring book pages we did together on one of my visits!

Robert describes this same phenomenon as he talks about his grandmother and mother’s relationship later in the progression of his grandmother’s Alzheimer’s:

“Now that my grandmother had, in a sense, disappeared, she was fully present to my mother for perhaps the first time in their relationship. Now that she was all but unreachable, she was finally available.”

I won’t give away the store by continuing to quote all my favorite parts of the memoir (which is really just about every page) but I will share Robert’s explanation of the title:

“I’ve always been a person to whom ‘forgive and forget’ has seemed absurdly unworkable…. since witnessing my grandmother’s Alzheimer’s, I’ve begun to wonder whether a small reversal wouldn’t better suit humanity. Maybe it would be more practical if forgetting preceded forgiving. Maybe happiness would be more easily achieved if we all made a practice of forgetting.”

A practice of forgetting. I’m going to work on that in my own relationships with people when I have a hard time forgiving. And if I follow in my mother grandmother’s footsteps and end up with Alzheimer’s one day, I hope that I will at least by then be able to forget the things I haven’t been able to forgive!

1 thought on “>A Practice of Forgetting”

Comments are closed.