PART I

Continuing from Part I, published here in my blog on March 5, Part II was published in the August/September issue of the Evangelist, the print-only newsletter of St. John Orthodox Church.

PART II: A Summary of the Definitions

Decisions About Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment: Part II

the Evangelist (July/August 1997)

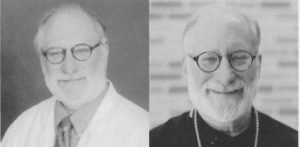

By Fr. William Cushman, M.D.

[In Part I of this series, Fr. Bill introduced the subject of the choices facing Orthodox Christians today in the realm of legal and ethical decision-making concerning medical treatment. This installment is a summary of the definitions and personal recommendations offered by Fr. Bill at the adult education class at St. John on June 14.]

Advanced Directives—An oral or written statement made by a competent patient which states his or her preferences regarding medical treatments, including but not limited to life-sustaining treatments or which designates a surrogate decision-maker who will make decisions regarding medical care in the event the patient is unable to do so. Types of advanced directives include: Living Will, Durable Power of Attorney for HealthCare (DPAHC). Treatment Preferences, or other “advanced directives,” a more recently orally expressed decision by the patient, takes precedent. A patient may change his or her advanced directive either orally or in writing at any time.

To be implemented, the following must be true: (1) The person must lack decision-making capacity and not be likely to regain that capacity in a reasonable time. (2) Any written advanced directive must be available to health care givers. (This should not be put in your will, since the will is usually not available until sometime after one’s death.) (3) The clinical situation must meet the description in the advanced directive. (4) It must not violate the law or the regulations of the institutions. (5) The physician and other caregivers must be willing to participate in carrying out the wishes of the patient. They cannot be forced to violate their own ethical, moral, religious standards. Transfer to the care of other care-givers willing to carry out the wishes of the patient is an alternative, if available.

Living Will—one form of written advanced directives. It may just be called an “Advance Directive.” This usually relates to a patient’s wishes concerning treatment options if he or she develops a “terminal condition” and is unable to make decisions.

Terminal Illness—a debilitating condition which is medically incurable or not treatable with current treatment options and which can be expected to cause death. Death will occur whether or not life-sustaining treatment is utilized, the application of which would only prolong the dying process (“delay death”). Recently this definition has been extended beyond those conditions where death is imminent to “debilitating conditions from which there is no reasonable hope of recovery,” i.e. coma or persistent vegetative state. I do not believe the same terminology should be used for these states, since death is not often imminent unless life-sustaining treatment is withdrawn.

Life-Sustaining Treatment—in a patient with a terminal illness, treatments which would “delay death.” Examples: resuscitation, “artificial nutrition and hydration,” mechanical ventilation, and dialysis.

Surrogate Decision-Maker—someone recognized as having the right to make health care decisions on behalf of the patient if the patient is unable to communicate his or her own health care decisions. State and federal laws often give surrogate deision-making responsibility priority to: (1) DPAHC (Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care). (2) Legal guardian (court-appointed). (3) Next-of-kin (order of priority). 1. Spouse, 2. Adult child (18 years of age or older), Parent, 4, Adult sibling. If there is persistent disagreement among next-of-kin of equal priority (e.g. adult children in the absence of a spouse), they must “appeal.” In the meantime, one should “err on the side of life” in my opinion. (4) Recently someone with a significant relationship or friendship with the patient has been added to this list, but he/she can only be a surrogate decision-maker when none of the first four categories is available or exists (unless they have been designed the DPAHC).

Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care (DPAHC)—Someone designated in writing by the patient to make health care decisions on behalf of the patient if the patient is unable to communicate his or her own health care decisions. The DPAHC should try to represent what the patient would have wanted and should follow any written “treatment preferences” provided by the patient, if able (should discuss and resolve any objections before agreeing to be DPAHC). This mechanism permits the DPAHC to discuss the specific medical situation with the physicians and other heal care providers involved.

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR)—a written order based on the request of the patient or appropriate surrogate decision-maker to not initiate cardiopulmary resuscitation if the patient has a “cardiopulmonary arrest.”

Medical Ethics Committee—(Ethical Advisory Committee, Biomedical Ethics Committee): most hospitals have one available to assist in clarifying or resolving medical ethical conflicts.

Euthanasia—literally “good death”—usually means giving drugs to end a person’s life, especially to avoid (further) suffering. May mean giving a patient the ability to commit suicide.

Physician Assisted Suicide—physician giving drugs or chemicals to end the life of a patient, at the patient’s request.

Fortunately, in June 1997 the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously agreed that there is not a constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia. However, there will probably be many battles concerning this in state legislatures.

My Recommendations:

-

Avoid “living wills” unless you are very clear about what circumstances they apply to. Be very careful about just signing a standard format for a “living will” or other advanced directive.

-

Consider appointing a DPAHC and a priority of alternatives to fill that role if the first is unable to serve.

-

Discuss your desires with whoever will be making decisions if you are unable to and try to gain guidance from the church.

-

If you have a terminal condition, try to receive care and comfort at home or in a hospice, especially if death is imminent regardless of treatment, but be alert to any inteercurrent illnesses which may be significantly benefitted or reversed by treatment.

-

Health care professionals may advise you with noble intentions, but may come from a very different theological and ethical perspective. “Principalism” as a basis for medical ethics is the norm today and is not necessarily consistent with Orthodox teaching or morality. Principalism is based on individual autonomy and rights and/or balancing benefits and burdens.

-

Seek guidance from your priest, who may also recommend other sources of guidance. . . and pray.

Dr. Cushman has been Medical Director of University of Tennessee Clinical Health since June of 2020. He is also Professor, Department of Preventive Medicine. Dr. Cushman served for 44 years at the VA Medical Centers in Jackson, Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee.

Father Basil Cushman has served as Associate Pastor at St. John Orthodox Church since 1988.