Continuing my journey through Lent with reflections from God For Us: Rediscovering the Meaning of Lent and Easter, I want to share a bit from the pages authored by the Orthodox poet and theologian, Scott Cairns. The essays on each day of Lent are written by different authors. Scott’s reflections are especially meaningful to me, probably because we share the Orthodox spiritual tradition. And also because he is a friend. And a poet.

It’s already the third week of Great Lent… we’re approaching the half way point of our journey. For some of us—those who have struggled to keep the fast, to live a more ascetic life, to pray more, eat less, love more, and forgive—the journey has been exhausting. For others maybe it’s not been so different than the rest of our lives. Those who have been reading my blog for several years know that I typically do “Lent Lite.” And this year has been the same. I’m not a strict faster. And I’m pretty lazy, spiritually. But I have striven to love more and judge less.

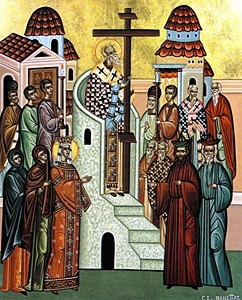

In Cairns’ entry on The Third Sunday of Lent, he says:

I must say that it took me a few years before I finally began to understand the efficacy of the Lenten fast; it took a good three years before I would come to know this somber period of preparation as a blessing.

Cairns writes about what he called “the ache of repentance, which is the beginning of our healing.”

Repentance. Not a word most of us like to think about frequently. But without it, we can’t really move forward. And moving forward, as Cairns says—“Don’t beat yourself up”—doesn’t necessarily mean going to extremes in our ascetic efforts.

In his chapter on the Third Tuesday of Lent, Cairns writes about what the church services are like during this time:

Much of the Lenten journey—the long and slow-moving services of the church, the dark vestments, and (most importantly) the coupling of prayer with fasting, and of fasting with almsgiving—has a way of quieting distractions and centering our minds within our hearts. These disciplines reconnect our minds to our bodies, assist our re-pairing our parsed and scattered persons into souls made whole; they also recover for us our often-overlooked connection with others.

I love that he adds that last part—about our connection with others. If we try to go this ascetic path alone, it’s not always fruitful. It needs to also be about love and forgiveness and alms and healing. And those things require the other—someone other than ourselves in the equation.

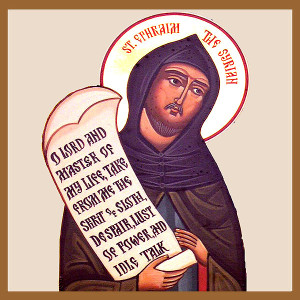

Cairns ends this chapter with the Lenten prayer most Orthodox Christians pray at every service during Great Lent, and often in our homes with our personal prayers. It’s known as the Prayer of Saint Ephraim the Syrian. I’ll close with this wonderful prayer:

Cairns ends this chapter with the Lenten prayer most Orthodox Christians pray at every service during Great Lent, and often in our homes with our personal prayers. It’s known as the Prayer of Saint Ephraim the Syrian. I’ll close with this wonderful prayer:

O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk.

But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to Thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother,

For blessed art Thou, unto ages of ages. Amen.