My new anthology ALL NIGHT, ALL DAY: LIFE, DEATH, & ANGELS comes out this Tuesday, June 20, with a launch party at Novel Books in Memphis at 6 p.m. Previously on my blog I did posts about all the contributors to the collection. You can find links to those here. But I didn’t blog about my essay in the collection, “Hitting the Wall,” because I wanted to save that post for today. For Father’s Day.

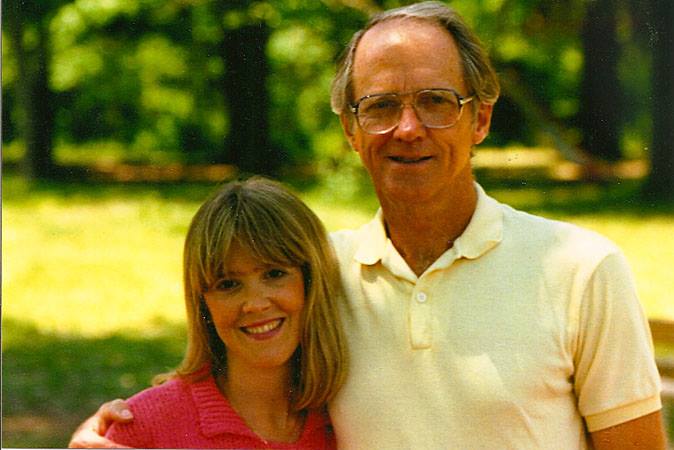

I don’t want to “give away the farm” with this post, but I’m having a hard time choosing an excerpt from that essay to post here, in honor of my father, Bill Johnson, who died in 1998. So I’ve decided to share the entire essay here. I hope it will make you want to buy the book and read all the essays, poems, and short story in the collection when it comes out on Tuesday. Without further ado, here it is.

Hitting the Wall

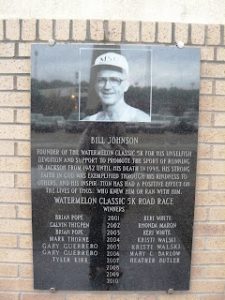

On the wall just outside the entrance to the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum in Jackson, Mississippi, there’s a single monument dedicated to my father—the man known as “The Guru of Running” in Mississippi. Etched in marble, the image of 67-year-old Bill Johnson, wearing a Mississippi State University baseball cap and a white running singlet, stands above the names of the winners of the “Watermelon 5K,” the race which he founded in 1982. Under his name are the dates of his birth and death: January 20, 1930—July 9, 1998.

Even seasoned marathon runners often experience “hitting the wall” around mile twenty of the 26.219-mile race. Dad taught the runners he mentored during his career about this experience, explaining how the body runs out of chemical energy and the runner can suddenly feel as though his shoes are full of lead. He was able to avoid this during many of the marathons he ran, with proper nutrition and training.

My father’s athletic career didn’t begin with running. At Mississippi State University in the late ’40s and early ’50s he was the starting pitcher on the baseball team—including the first year State won the SEC championship—and also lettered in golf and basketball. After a brief stint on a farm league in Florida in the late ’40s, he gave up baseball and became a championship level golfer, winning the City of Jackson (Mississippi) and numerous country club invitationals throughout the state during the ’50s and ’60s. When he could no longer play scratch golf, (always shooting par or better) he turned in his cleats for running shoes. Dad had been a smoker for twenty-five years, and after quitting in the early ’70s, he knew he needed to do something to keep the weight off. Both his parents had died of heart attacks, so Dad set out on a path of low-fat eating and intensive aerobic exercise.

He traded his two-martini business lunches for noonday runs with a group of men at the YMCA. This was before the

running craze hit, so everyone said they were “hog wild” about running, and they eventually became known as the “Hog Wilds” and even had running shirts printed with that insignia. By the end of the ’70s Dad was running 5Ks, 10Ks, and even marathons. He was only fifty-two years old when he retired from the life insurance business and opened “Bill Johnson’s Phidippides Sports,” a retail business specializing in athletic shoes, clothes, and informal training advice.

Life was good for Bill Johnson for the next fifteen years. From 1982 to 1997 he enjoyed a healthy lifestyle and a successful business. He ran allthe big marathons, like Boston and New York, several times. One year he even competed in a triathlon. All this after age 50. Wanting to include the family, he built an aerobic dance studio adjacent to his store, which my mother oversaw. I taught aerobics there from 1982 until 1988, when I moved away from Jackson, and those were without a doubt the healthiest years of my life. To say Dad was a positive role model to those around him would be an understatement. Six-foot-two, with a slim runner’s body, sky blue eyes and a mischievously dimpled smile (he always reminded me of Clint Eastwood), he seemed invincible. But all that changed abruptly in 1997.

The Marathon Begins

Well, it actually started changing in 1995, when Dad first told his physician that he felt something strange, a twinge when he took a deep breath. Early chest x-rays showed a small, vague, gray area, but the bronchoscopy and needle biopsy were negative, so the doctors weren’t concerned. But a life-long athlete is so attuned to his body that he can pick up signs others miss, so Dad went back again and again, asking for more x-rays. By 1997 the gray area proved to be a malignant tumor, bigger than any wall he had ever hit running marathons.

The next fourteen months were trying times for our family. Dad went into the hospital on May 13, 1997, expecting to have only one lobe of his right lung removed. During the surgery, a 4.5-centimeter adenocarcinoma with metastatic disease was found in one lobe, with involvement of a lymph node. A 5-millimeter lesion was discovered in another lobe, which also had metastasized. Additionally, a third tumor “of long duration” was found. The surgeon performed a pneumonectomy—the removal of his entire right lung—but unfortunately he wasn’t able to completely eradicate the metastatic process that had begun to invade Dad’s body.

Bill Johnson entered surgery a seasoned athlete and came out a semi-invalid. He would never again drive a car. In a few months he would no longer be able to take slow walks around an indoor track. He would become confined to a wheelchair and would require a portable oxygen tank at all times. Most people would have caved under such an emotional glycogen depletion, but Dad’s training as a runner, combined with the community’s image of him as hero—not only in athletics, but also in the spiritual and civic worlds—kept him from bonking at the twenty-mile marker of his final marathon, his race against death.

What he didn’t know then was that some of the recommendations made by his physicians were futile attempts at prolonging the inevitable. Maybe they saw my father as an excellent candidate for experimental drugs because of his physical and spiritual strength. Maybe his physicians were urged on to prolong his life, even at the cost of greater suffering on Dad’s part, because of the community hero status that he had acquired. Whatever their reasons, a year after the surgery, Dad’s body was buckling under the weight of the hero’s burden he’d been carrying most of his adult life. He suffered anxiety, hot flashes, weight loss, fever, chills, infections, depression, panic attacks, nausea, extreme confusion, and a severe allergic reaction to one of the chemotherapy drugs.

“Page the Doctor!”

On one of my visits from Memphis, I drove Mom and Dad to the oncologist’s office for his first chemotherapy treatment. The nurses greeted us with an air of hopeful enthusiasm. Once the blood work was done and Dad was set up in his recliner chair, the first round of Taxol began to drip into his veins from the bag hanging above his head. Mom and I pulled up chairs to keep him company, but in less than a minute Dad’s face turned bright red and he began gasping for air. The room quickly filled with medical personnel and I heard someone say, “Page the doctor!” They unhooked the IV, administered oxygen and gave him an injection of some sort. Color returned to his face and we all began to breathe again, as if all the air had left the room and returned just as suddenly.

“Taxol is a fairly new drug,” the doctor explained when he arrived. “We were hoping for a breakthrough, but Bill had a rare allergic reaction to it, so we’re going to use Carboplatin and Navelbine.”

That was in August of 1997. He received four full months of this cocktail. The physician’s notes from a follow-up visit in January of 1998 reported that “his tolerance for this was good.” But the notes also revealed that Dad had anxiety and hot flashes, and was seen in the emergency room in October for fever and chills. A large nodule in the left lung was thought to be pneumonia, and a splattering of small nodules was also present. The radiologist “thought there were more small nodules in the left lung than before and that some of these had increased in size.” But the oncologist reviewed the CT scans and noted that they were performed at different intervals, which could have accounted for an appearance of growth in size.

It was difficult to get straight answers, and I often felt, during this time, that the oncologist wasn’t completely transparent with my parents. But I was 200 miles away, and my parents were intelligent and capable of asking questions themselves. Weren’t they? Years later, as I read the following paragraph near the end of the doctor’s notes from that January visit, I regretted that I had not been more involved in the early stages of Dad’s treatment:

“I discussed these findings with Mr. and Mrs. Johnson today. I told them that I did not think that we needed to intervene at this time. If this is metastatic disease, then subsequent follow-up will be able to verify this. These lesions are too small to biopsy now. Clinically he is doing well and does not have symptoms to suggest progression.”

If this is metastatic disease? The first paragraph of the report stated that the surgery done the previous May revealed “intrapulmonary metastatic disease.” Wasn’t that the reason for the four tortuous months of chemotherapy? The notes did not indicate that any end-of-life discussion took place with my parents on that visit. Instead, they mentioned TB skin tests, steroid therapy and testosterone shots. While I was grateful that the physician had seemed to be treating Dad’s physical condition as a whole, I was disturbed by his apparent lack of directness concerning Dad’s prognosis. Mom and Dad seemed to have been left to their own intuition. At some point Dad expressed regret for having gone through the chemotherapy, saying that the “cure”—which was not really a cure—was worse than the disease. He wondered what the quality of the final year of his life might have been like had he chosen a different path. What if he had been counseled differently about his options? What if he had not allowed his body to be shot through with poisonous chemicals all those months? But it was too late for “what ifs.” It was time to face the inevitable.

End-of-Life Preparations

Mom was Dad’s primary caregiver, with help from friends and neighbors who took turns staying with Dad while Mom ran errands or took a much-needed break for herself from time to time. At some point during those fourteen months, on one of my frequent visits from Memphis, the three of us sat down to talk about end-of-life issues. Mom and I went to the funeral home to make all the arrangements, and Dad made his wishes clear to us in his Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care. He wanted no “extreme measures” near the end. He wanted to die at home, with help from hospice staff. My parents didn’t show their emotions very often, but on that day, Dad could barely say the words aloud without choking up, and Mom and I were swallowing our tears as we held our caregivers’ smiles intact.

I was so glad when Dad decided to quit chemo. The physical race was over. It was time to gather emotional and spiritual resources for the most important and difficult leg of the marathon. It was time to get over the wall. What the three of us shared during the final week of my father’s life was the best and worst that we can know in this life. We labored through the days and suffered through the nights, touching heaven and earth simultaneously.

I watched my parents’ marriage of forty-nine years turn on its head under the stress of my father’s impending death. With all the distractions removed—business, running, travel, civic and social engagements—they were left face to face with their brokenness. Fortunately, they had soft hearts, a strong faith, and an enduring love. I watched as their frustration and anger leaked out. Then I watched with admiration at the reconciliation and forgiveness that followed those moments of raw truth and emotion. One night I went into the living room and found them holding hands and crying.

“What’s wrong?”

Dad managed a weak smile. “Your mother has been such an angel all these months, and I haven’t been an easy patient. I’ve been irritable and hard to please, and it finally got to her.”

I looked at Mother as she wiped her eyes and blew her nose while getting up to find more tissues.

“Mother?”

“Oh, he hasn’t been a bad patient. I’m just tired is all.”

But Dad wanted me to understand. “I’ve asked her to forgive me and she feels guilty, but she’s only human. If the tables had been turned and she had been the one who was sick, I could never have taken this good care of her.”

It was more emotional intimacy than I had ever seen them share in my forty-seven years as their daughter. My tears mingled with theirs as the three of us held hands and prayed together. As I returned to Memphis from that visit, I had a sense that the end was near, and it was hard to leave them.

They met with the hospice social worker the following week, and she helped them get set up with a hospital bed, portable toilet, and other supplies they would need. She shared with them the hospice philosophy for end-of-life care, and left them a booklet to read, which Mom shared with me when I returned to Jackson for what would be the final week of Dad’s life. The literature was excellent. We learned that hospice is a philosophy of care with a completely different approach than most of the cure-focused healthcare system. The hospice philosophy embraces death as a natural part of living, instead of something to always fight against. It’s all about comfort and pain relief for the dying, and doesn’t seek to either prolong life or hasten death. I was better able to wrap my head around the concept of “letting go” than Mom was, so she took a step back and asked me to take over as primary caregiver for those final days.

Fed by Angels

I think one of the most difficult things for family members to accept—especially for a wife who has been cooking for her husband for almost fifty years—is the patient’s decreasing appetite. What southern woman, or any woman for that matter, doesn’t associate cooking and feeding with nurturing and loving? So, when Dad began to refuse to eat, I reminded Mom what the social worker had told us, that he was being fed by the angels as he moved away from earth and towards heaven. He no longer needed earthly food, and his transition from earth to heaven would go more smoothly if we would embrace the process and not hold onto him too tightly. As the cancer began to shut down his vital organs, it was difficult for him to even swallow the tiny bites of applesauce into which I mixed his morphine tablets after grinding them with the back of a spoon.

Lung cancer is a relentless monster that literally sucks the air from its victim’s world, resulting in a feeling of perpetual suffocation that rivals the pain of the worst forms of bone cancer. Dad’s body fought the monster with more vigor than most of its victims because he was a trained marathon runner. His heart was so strong that it literally refused to stop beating, for days and perhaps months after a less conditioned organ would have given up. The irony of his condition was a cause of spiritual and moral confusion for Dad. He had done all the right things—he had quit smoking, embraced a lifestyle of low-fat foods and running over fifty miles most weeks, and had continued to be a leader at his church and in the community. For the first time in his life, he was angry with God. He wrestled as Jacob had with the angel, until he finally allowed himself to collapse into God’s arms. I witnessed this struggle with reverence, and with thankfulness for the time he had been given to prepare to meet the God he had loved and served for sixty-eight years.

Friends from the running community visited less often as they witnessed his decline. Their hero had been reduced to an invalid in diapers, and it was more than they could bear to see. Elders from his church came on Sunday nights to anoint him with oil and to pray for his healing. When no apparent miracle arrived, their visits also decreased. When a colleague from Dad’s former business firm and his wife came to visit, just a few days before Dad’s death, they broke down in tears at the sight of this fallen giant of their community. I had been especially close to this couple, having babysat for their children many years earlier, and so I encouraged them to spend some time talking with Dad. They shook their heads and apologized. They just couldn’t do it.

My brother had been estranged from our family for many years, but as it became obvious that Dad had only a few days to live, we summoned him for a reconciliatory visit. As he asked for forgiveness and was received into his father’s embrace, images of the Prodigal Son flooded my heart. Here was yet another reason to be thankful for this time of preparation, as painful as it was for Dad, and for all of us. We might think we would prefer a sudden death and the avoidance of suffering, but suffering offers opportunities for redemption. Hospice care provides the venue. It’s up to the dying and their loved ones to take advantage of this unique setting.

As Dad’s anxiety increased, he found it insufferable to lie in bed. He wanted to get up and walk around, which took great physical support from his caregivers. Mom and I hired sitters to relieve us from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. so that we could sleep, but my ears were so tuned to Dad’s voice that I often found myself running down the hall in the middle of the night, afraid that I would miss his passing. One night, after we had helped Dad get up and take a few labored steps—his arms around each of our shoulders for support—we put him back in the hospital bed, only to have him ask to get up again immediately. He was over six feet tall, and although he was a mere shadow of his former self, my back was screaming with pain and my emotions were raw and sleep-deprived. After hours of these repetitive transports from bed to floor and back to bed, my strength failed. I crawled onto the bed beside him and physically restrained him with my arm. I cried. I sang to him. I prayed aloud. I played his favorite music on a tape recorder we had set up beside his bed. But he cried out with all the strength he had left, “Please let me up. I can’t breathe.”

I asked if he wanted me to give him more morphine so that he could sleep and he whispered, “yes.”

“You might not wake up if I do this, Dad. You might not be able to talk with us any more. Are you ready for that?”

His answer was clear. “Yes.”

A New Physician

It was early morning and I called the hospice nurse to ask for permission to increase the morphine dose. She said she would have to ask the doctor. It seemed like an eternity before she called back with the news: the doctor wouldn’t allow the dose to be increased. He said he would come by later that day to see Dad first. Later that day? The nurse understood my urgency and candidly encouraged me to find another physician to sign the orders, saying that Dad’s physician had a reputation for not cooperating with hospice nurses.

First I called the current doctor, who validated what the nurse had told me. He would not allow the hospice nurses the authority to increase medications as needed. “They are only nurses. They are not physicians.”

“But they are the ones who are here with us,” I protested. “They are the ones taking care of my father! You don’t know what it’s like. You don’t see how he is suffering. You are not here!”

In that moment I was no longer the child. I became the adult my parents needed me to be. I fired the doctor over the phone, called another doctor—a dear friend from my parents’ church, who had also seen Dad in his pulmonary practice during the past three years—and asked him to sign the paperwork, allowing the hospice nurse to increase Dad’s meds. He took care of it immediately, and the hospice nurse called and said for me to increase the morphine. The doctor also said he would drop by to see Dad in an hour or two, which he did.

At this point you might be thinking, what prevented me from making the decision to increase the dose on my own? I thought about it, more than once. No one would have known, and I could have spared myself—and more importantly, my father—several more hours of suffering. But it wasn’t that simple.

I was torn between the immediacy of Dad’s discomfort and the moral implications of my actions. Mom had pretty much checked out, emotionally, by that point, so I was alone with the decision. Even with the new doctor’s orders to increase the morphine, I was plagued with guilt and ambivalence. Would I be shortening my father’s life?

Palliative Sedation

The literature wasn’t clear on this issue. Eleven years later a front-page article in The New York Times (December 27, 2009) chronicled the ethical, medical and emotional struggles of several terminally ill patients and their family members. “Hard Choice for a More Comfortable Death: Drug-Induced Sleep,” by Anemona Hartocollis, introduced terminology like “terminal sedation” and “palliative sedation” to the general public. One of the physicians Hartocollis interviewed, Dr. Edward Halbridge, medical director at Franklin Hospital in Valley Stream on Long Island, was asked whether the meds that rendered his 88-year-old patient unconscious might have accelerated his death. “I don’t know. He could have just been ready at that time.”

Another physician, Dr. Lauren Shaiova, chairman of pain medicine and palliative care at Metropolitan Hospital Center in East Harlem, had drafted a twenty-page document with guidelines for palliative sedation. Seeking even more clarity in an area ridden with ambiguity, Dr. Paul Rousseau contributed an editorial to the Journal of Palliative Medicine in 2003—while he was a geriatrician with Veterans Affairs in Phoenix, Arizona—calling for more systematic research and guidelines. His work noted different degrees of palliative sedation, including a level termed “intermittent deep sleep.”

Hartocollis’ article referenced several more physicians and spotlighted numerous personal stories to illustrate the complex issues at stake. A capstone, for me, was learning that in 2008, the American Medical Association issued a statement of support for palliative sedation, after the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine condoned “palliative sedation to unconsciousness.”

As I read this comprehensive article in the midst of penning the story of my father’s death many years later, I wondered if the decision I made in July of 1998 would have been any easier—or different—had this information been available at the time. Left alone with only my conscience as my guide, I made two phone calls.

First, I called my husband—an internal medicine physician who also happens to be an ordained Orthodox (Christian) priest. And then I phoned my pastor in Memphis. Neither of them could—or would—tell me what to do. I think they both sensed that there might not be a “right thing” to do in this situation. And so the two men whose love and wisdom I trusted most in the world were silent. Somehow I found the strength to push through the silence. I hung up the phone, asked God for mercy, and walked into the kitchen to prepare what would probably be the last dose of medicine my father would be able to swallow.

Mother went to her room, postponing the reality as long as possible, I think. Worried that Dad wouldn’t be able to swallow the larger dose, I used as little applesauce as possible, working like an artist, grinding pigments with pestle and mortar until they slid smoothly from brush to canvas. Alone with Dad in the living room, I told him that the doctor had given permission for a larger dose. He nodded. I reminded him that he might not wake up. Did he want me to get Mom? Again he nodded. First I helped with the medicine, which took two or three tries before he finished the full dose. And then I wiped his mouth gently and walked down the hall to Mother’s bedroom.

We returned together, and I witnessed my parents’ final conversation in this life. A few minutes later, Dad closed his eyes and went to sleep.

The hospice nurse came by later, as did the physician, and each of them assured me that Dad was resting peacefully and was not in any distress. My instructions were, “If he wakes again, give him another dose of the morphine.”

When the sitter arrived for the night shift, Dad hadn’t moved, but his breathing was steady, so Mom and I opted for a few hours of sleep. Early the next morning the sitter knocked on the door to the room where I was sleeping. “Mrs. Cushman, I think you and your mother should come be with him now.”

The Finish Line

I flew out of bed, pausing briefly to call to Mom through the open door of her room, and she followed me quickly into the living room. Once we were at Dad’s side, the sitter slipped quietly into the kitchen, allowing us privacy with Dad. Her hospice training had taught her that the ragged breaths he was drawing were signs that the end was near. We had read in the hospice literature that sometimes a dying person experiences a final surge of alertness and energy, just before the end, and we didn’t want to miss it. As we stood, and later sat, on either side of his bed, he slept through much of his final morning. And then it happened.

Early on the afternoon of July 9, Dad woke briefly from his coma-like sleep, smiled, and made eye contact with Mom and me for the first time in twenty-four hours.

“I love you, Daddy.”

Mother could barely find her voice. “I love you, sweetie.”

“It’s okay, Dad. I’ll take care of Mother. You can go now.”

He responded to our words by squeezing our hands. And then he was gone—the most powerful sunset I have ever seen.

As we stood there holding his hands, I was struck by the complexity of my grief, which was infused with an uneasy mixture of relief and

exhaustion. But then my mother’s pain, which she had contained for fourteen months, poured from her mouth like the sounds of a woman in childbirth as she collapsed onto Dad’s chest. I ran around to her side of the bed to support her, and we stood there for a long time, weeping. Finally I reached for my little red Orthodox prayer book and began to read the Prayer at the Death of a Parent. Mother regained her strength and joined me as we read together the Prayer at the Death of a Spouse. And then we read the 23rd Psalm, which was Dad’s favorite. I had visions of him running past the twenty-mile marker as we read the fourth verse: “And yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” He had made it over the wall.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad. I miss you every day. You are my hero.