This is the sixth and final entry in my weekly series of reflections on Nicole Roccas’s book TIME AND DESPONDENCY: REGAINING THE PRESENT IN FAITH AND LIFE, which I’m reading during this season of Great Lent. If you missed my first five posts and would like to catch up, here they are, in order from first week through fifth:

This is the sixth and final entry in my weekly series of reflections on Nicole Roccas’s book TIME AND DESPONDENCY: REGAINING THE PRESENT IN FAITH AND LIFE, which I’m reading during this season of Great Lent. If you missed my first five posts and would like to catch up, here they are, in order from first week through fifth:

For some reason Nicole skips Chapter 6, “Prayers From the Present,” altogether in the study guide that she created to go with the book. I read it before reading the “assignments” for this week, and found some treasures within:

One of the snares of despondency is to assume that more is always better…. [we] somehow get an idea in our minds that we should be praying longer harder, more intensely. We forsake the virtue of knowing ourselves—and our limitations—and cling instead to our fictional superselves.

This was an important “takeaway” for me from the book, because in years past I have gone to one extreme or another (which is my nature) during Lent. Some years I have rebelled against the whole endeavor, and other years I aimed too high. This has been my best experience of Lent in the thirty years since I’ve been Orthodox. Undoubtedly one reason is that I quit drinking six months ago, so this is my first alcohol-free Lent. But also, I’ve approached the season with a kindness towards myself and others that has permeated my Lenten practices—fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. So, when I read in Chapter 6 about what Nicole calls “counter-statement,” I embraced her approach of using short phrases from the Psalms or short prayers throughout the day to “counter” the temptations life sends our way. As she says:

There is also an aspect of counter-statement that is lively—even sassy. These prayers are quick, punchy, and purposefully confrontational. They carry an energy all their own, helping to reignite the vigor despondency all but stifles.

Sassy prayers. I like that. It reminds me of the little quote I have taped to the lamp beside my computer that says, “Be the kind of woman that when your feet hit the floor each morning the devil says “Oh crap, she’s up!”

I see these sassy prayers as a wonderful tool for what Nicole addresses in Chapter 7, “Stepping Stones Back to the Present,” where she talks about shifting toward “everyday strategies to mitigate despondency’s stranglehold on our lives.” This is the chapter where earlier she addressed humility, patience and perseverance, gratitude, confession and community, and labor and leisure, all of which I commented on in previous posts. This final week she surprised me by including humor as the final stepping stone. As she says,

The virtue of humor is likely among the last items one would expect to find in a book on despondency—which is why I’ve saved it, literally, for the end of this book…. humor helps us recover the vitality despondency robs us of.

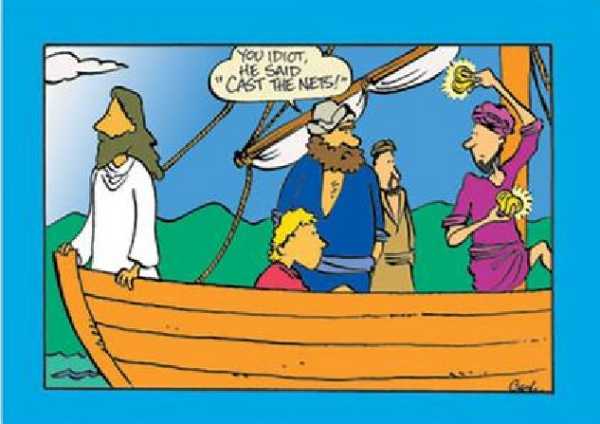

And within the topic of humor, she addresses laughter:

Simultaneously, laughter causes an upsurge of energy within us. Riding on the wings of laughter, our soul can jump up through the cracks of our defenses and grab hold of ideas we would otherwise reject or overlook…. Adopting a more playful attitude toward ourselves and our shortcomings pulls us out of despondent thinking more swiftly than any other approach. It’s not a permanent solution, of course, but even a few seconds’ smile is enough to get our foot in the door of our own mind and start to redirect it toward the heart.

Anne Lamott calls laughter “carbonated holiness.”

Anne Lamott calls laughter “carbonated holiness.”

I have a dear friend who has Lewy Body Dementia. She’s younger than me, but the disease has already taken away her ability to perform many of life’s everyday functions. She used to have the best sense of humor of most anyone I know, and I miss her laugh. So each time I visit her, I make a point of finding something humorous to say. And once she starts laughing, her whole countenance changes—from the dark, scary, negative images that the disease is pouring into her mind, back to the funny woman I once knew. I try to help her find some happiness, if only for a few minutes.

It might seem strange to be talking about humor and laughter during the last week of Lent and just a week before we enter Holy Week. (Or for my Catholic and Episcopal friends, as you enter Holy Week today.) But I think Nicole makes a good case for its proper use in our spiritual lives, as well as for our mental health. As she says at the conclusion of this chapter:

Wise humor chisels a crack in despondency just wide enough for our souls to slip through, get some fresh air, and see the bigger picture.

In the final chapter of the book, ““Re-presenting Reality,” Nicole brings us back to the focus, to the reason for all the talk about despondency to begin with. We are preparing to enter into the celebration of Pascha, of Christ’s resurrection:

. . . not to commemorate the Resurrection, as though it were (only) a historical event, but to re-present it—to make Christ present among us as a living fact…. Likewise, we live in the present only inasmuch as we abide in His presence.

This is why so many of our Paschal hymns use the present tense, with phrases like, “Today is the day of resurrection,” and “He is risen!” The Orthodox celebration of Christ’s death and resurrection aren’t just remembrances. We enter into His suffering, and then into the joy of His resurrection in the services of Holy Week and Pascha. As Nicole says:

. . . let us have the courage to profess with St. Paul that today is the day of salvation—not two thousand years ago, not happily ever after in heaven, not when we finally manage to get ourselves sorted out, but today. . . . This is what we lose when we retreat into the slow, apathetic death of despondency. And this—all of this—is what we stand to regain when we return toward home and let the scales fall from our eyes.