I’m reading my fourth and fifth books of 2017 simultaneously, as I often do. Especially when they’re so different. That way I have choices: which book to read with my morning coffee? What am I in the mood for with a cocktail in the evening? Which one will I take to bed with me?

I’m reading my fourth and fifth books of 2017 simultaneously, as I often do. Especially when they’re so different. That way I have choices: which book to read with my morning coffee? What am I in the mood for with a cocktail in the evening? Which one will I take to bed with me?

One of my current reads is Angela Doll Carlson’s Garden in the East: the Spiritual Life of the Body. Two years ago I reviewed another of Carlson’s books, Nearly Orthodox: On Being a Modern Woman in an Ancient Tradition. There was so much I could relate to in that book, so I was excited to see her book on the body. See, I’m a bit obsessed with my body. Always have been. Maybe because of my childhood sexual abuse. Maybe because my mother always told me I was fat. Maybe because I couldn’t stop comparing myself to the beauty queens on the Ole Miss campus when I was a student there in 1969-70. If you’ve been reading my blog very much, you know that I always struggle with weight. I worked so hard to lose 17 pounds in the last few months of 2015 and early months of 2016, only to gain back most of it last summer. I’ve been stuck with it ever since, and it sends me into bouts of depression and self-loathing on a regular basis. Not to mention the discomfort of my clothes not fitting. I don’t know what I’d do without my extra large yoga pants.

This morning I went to my annual physical exam—my first since turning 65. I am so grateful for my wonderful internist. She’s (1) smart, (2) communicative, (3) energetic, and (4) non-judgmental. I bubbled over with an apology for the weight gain before she could even bring it up, and she made no comment at all. No lecture. She knows that I will do something about it when I can. Or I won’t. But her words won’t make a difference.

But Angela Carlson’s might. Using the metaphor of our body as a garden, she writes about the importance—and the joy—of tending that garden. Of loving it. These words remind me of how I feel when I remember that I could be dead or paralyzed after my wreck in 2013, which left me with pretty continuous aches and pains (broken neck, leg, and ankle, all full of permanent hardware):

In my best moments, I am grateful to be walking around, upright and active. In those moments, I am not noticing the forward jut of my head, misaligned form age and bad postural habits built up over time. I am not worried about the creaking of my knees or my elbows. In my best moments, I am thinking about deep issues like world peace and schoolyard bullies and what’s for dinner.

Oh how I love those moments when I am not obsessing over my body! For me, those “best moments” usually involve writing, editing, reading, or watching an excellent movie or television drama. Sometimes they involve music. Or taking in the beauty of a spectacular sunset, at the Mississippi River (three blocks from my house) or a beach on the Gulf of Mexico. I can easily pour out my love and appreciation for these things and places that bring me joy. So why can’t I express that same love for my body, my garden I’ve been given to tend? Carlson says:

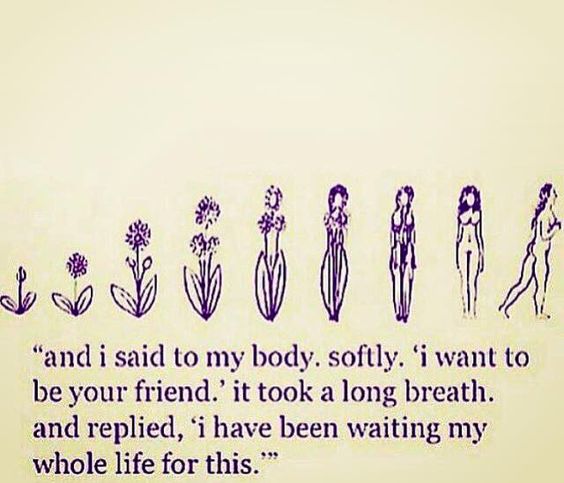

This body is a garden and it is mine. I am responsible for its care. I am responsible for the words I use when I describe it, even to myself, even when I’m alone.

Carlson continues the garden metaphor, even laying out for us parallels involving loving and caring for both, which includes the way we speak to our garden. I’ve never been much into growing things, and I’ve certainly never spoken to my plants. But I used to talk to my cat all the time. And the tone in my voice told her she was loved, just as the tone in our voices sends a positive message to our children, our spouses, our friends. So how should we speak to our bodies? Carlson says we should tell our body that we love it. That it is good and strong and beautiful—an amazing mystery created by God and given to us to cradle our spirits and allow our souls to grow and be happy and at peace.

Maybe if I learn to talk to my body, I’ll eventually learn to love it. Or at least not to hate it.

Wishing you well as you bring more positive emotions to your relationship with your body. I think that some of our church traditions have contributed to our separating body, mind, and spirit, instead of looking at and loving all as a unitive whole. I have been learning a lot from Richard Rohr about wholeness and inclusion. I think it is most difficult to apply it to ourselves, but I am trying.

I love Richard Rohr’s writing, Joanne. Thanks for the encouraging words.