>Pat Conroy (The Prince of Tides) and his wife, Cassandra King Conroy (The Sunday Wife) made me want to write fiction. And I did. I drafted a novel back in 2006-7 called “The Sweet Carolines.” But I hadn’t studied the craft and it showed. So did the fact that I was trying to hide truth in fiction, and I wasn’t up the task, as the Conroys were.

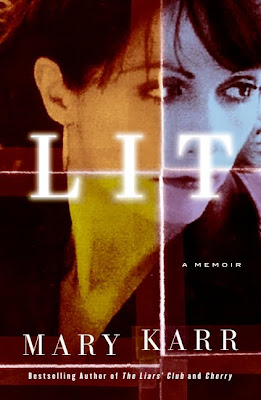

But when I read Mary Karr’s memoirs, “The Liar’s Club” (about

her childhood) and “Cherry,” (her teenage years) I strapped my courage on and began to learn to “tell it true.” 8 published essays and two unfinished memoirs later, I’m still struggling with the long form of creative nonfiction, the memoir. So when one comes along that blows me out of the water, I find myself wanting to take every finely crafted word of it into my being, hoping that just by reading and studying its genius I will be transformed into a better writer.

“Lit”, Karr’s “sequel” to her earlier memoirs, was chosen as one of the top 5 nonfiction books of 2009 by the New York Times. And yet she begins the prologue (an open letter to her son) with these words:

“Any way I tell this story is a lie….” It’s Karr’s nod to the frailty of human recall, especially when one’s life was filled, as hers was, with so much abuse.

After I finished reading “Lit” yesterday, I looked in the back, where I had listed 27 quotes that had significance for me, and I thought, “oh, dear, This is going to be a long blog post.” So, grab a cup of coffee first and hold on for the ride.

Unlike her previous memoirs, “Lit” is written by Mary Karr, the adult. It’s still got the same gritty, small-town-Texas-girl honesty, but tempered with what I think she would call grace. It’s the story of her efforts to escape the pain of her past while raising a son as a single (divorced) mother. It’s the story of her abuse of alcohol, but it’s also the story of her recovery. And the best part, for me, is that in the process she found God and the church. (Read more about her spiritual journey in her book, “Sinners Welcome.”)

Unlike her previous memoirs, “Lit” is written by Mary Karr, the adult. It’s still got the same gritty, small-town-Texas-girl honesty, but tempered with what I think she would call grace. It’s the story of her efforts to escape the pain of her past while raising a son as a single (divorced) mother. It’s the story of her abuse of alcohol, but it’s also the story of her recovery. And the best part, for me, is that in the process she found God and the church. (Read more about her spiritual journey in her book, “Sinners Welcome.”)

And like my favorite other memoirists—Kim Michele Richardson, Haven Kimmel, Anne Lamott, Augusten Burroughs, and Neil White—Karr writes with honesty and without anger.

Perhaps the most significant concept I gained from the book, as one who struggles with addictive behaviors, is Karr’s portrayal of one of the most devastating affects of substance abuse in a person’s life—the way drinking, in her case, numbs one to real life:

“Which insures that life gets lived in miniature. In lieu of the large feelings—sorrow, fury, joy—I had their junior counterparts—anxiety, irritation, excitement.”

My heart skipped a beat when I read those words, over and over several times, early in the book. And 100 pages later, when she writes of her feelings at her son’s birth (she was sober for her pregnancy and delivery) she says:

“Joy, it is, which I’ve never known before, only pleasure or excitement. Joy is a different thing, because its focus exists outside the self—delight in something external, not satisfaction of some inner craving.”

And this was before she found God. 100 pages later, after being incarcerated in the “Mental Marriott,” she returns to this truth:

“In my life, I sometimes knew pleasure or excitement, but rarely joy. Now a wide sky-span of quiet holds us. My head’s actually gone quiet…. as if some level in my chest has ceased its endless teetering and found its balance point.”

Although my life was no where near as crazy as Karr’s, I relate to the sexual abuse, and to having a mother who wasn’t capable of having a healthy, loving relationship with her children. And like Karr, I recognize that our mothers’ behavior wasn’t born in a vacuum:

“Drinking to handle the angst of Mother’s drinking—caused by her own angst—means our twin dipsomanias face off like a pair of mirrors, one generation offloading misery to the other through dwindling generations, back through history to when humans first fermented grapes….

“How do you get past it, I ask my shrink, when you never got that sense of acceptance and security as a kid?

“You’ve got to nurture yourself through those instants, he says, recognize the source of the misery as out of kilter with the stimulus. Realize you’re not lost. You’re an adult.”

But her inner child struggles even into sobriety. When she calls her mother to visit her while she’s in treatment, and her mother has other plans, Karr’s response is candid:

“After she hangs up, I cry because part of me still wants to drag her behind my car. But the other part still wants to crawl into her lap.”

Ah, there’s the rub. I feel it every time I visit my mother in the nursing home. But it’s fading, as I’m beginning to allow God to heal those wounds. (If you missed my post after visiting Mom in mid-November, it’s here.)

A few quips will illustrate Karr’s struggle with drinking. First, after a day

on which she lost her temper with her toddler son and lies to her husband about her drinking, she re-runs the day in her mind while taking a shower at dawn:

“I stand in a cloud of shower steam, the former night’s conviction to quit solid, though it’s daunting to face unmedicated whatever’s beyond the plastic curtain I’m scared to draw aside. By afternoon I can’t abide Mr. Rogers asking me to be my neighbor without a cocktail.”

She bares her soul and spins her story with literary finesse:

“… I’d rather drink than love.”

60 days into sobriety, she gives in to a martini, and by the end of the evening she’s drunk again:

“That inverted triangle of glass-with frost at its lip and a speared olive at its nexus—is the perfect accessory to the place…. And I don’t even consider canceling the order, since just placing it shifted some geological plates around my innards. It lends an almost sexual thrill to waiting for it. Delicious, crossing the threshold into abandon.”

But after a while, the alcohol doesn’t work:

“A drink once brought ease, a bronze warmth spreading through all my muddy regions. Now it only brings a brief respite from the bone ache of craving it, no more delicious numbness.”

A physician explains it to her:

“You’ve passed some line where it works, she says. I used to try to figure it out. Maybe it’s how the pancreas handles sugar, or some enzyme we give off when we drink that sets up a craving. But whatever line it is, you’ve crossed it. Somebody who’s crossed the line and craves liquor like you do and wants to keep drinking is like a pickle who wants to be a cucumber again. You can’t. It’s over.”

Karr writes about her first night in recovery with in-your-face clarity:

“The ferocious internal motion I’ve been praying would end finally—almost in a single nanosecond—stops. It’s a pivot point around which my entire future will ultimately swivel. That first night, kneeling before the toilet, I let go, as they say. Or call it the moment my innately serotonin-challenged brain reached level X.”

“Lit” is filled with real-life action, dialogue, and reflections on what the ride was like. Even near the end, when she writes about finding an agent and writing “The Liar’s Club,” (about her childhood) she’s terrified:

“To write the stuff down is no cakewalk, since memories from that time can ravage me. But after I get home, I start getting up mornings at four or five, praying to set down words before Dev comes down…. I unplug the phone and apply my ass to a desk chair. Some days, I actually hear my daddy telling me stories, almost like he’s risen up to ride through the pages with Mother and our whole wacky herd.”

As a new convert to the Catholic faith, Karr brings her spirituality to her work, as O’Connor did, without a smidgeon of self-righteousness. In fact, she is perhaps most honest about her spiritual journey:

“After ten months praying in a cave in Manresa, St. Ignatius received a vision that permitted him to see God in all things—the stated goal of his Spiritual exercises…. This doesn’t innately appeal to me. Despite my conversion, I don’t much care to see God in all things…. It’s not virtue that leads me to the Exercises but pain. Only a flame-thrower on my ass ever drives me to knock-knock-knock on heaven’s door. Pain, in my case, is the sole stimulus for righteous action.”

She befriends a nun, in whose presence she feels “like some slutty Catholic schoolgirl.” But after realizing that the Sister doesn’t judge her, she begins to relax into the relationship. Finally the Sister says:

“Let’s eat a cookie and pray for each other’s disordered attachments. Mine involves pride and cookies.

“Mine, I say, involves pride and good-looking men.

“Together we bow our heads.”

2 thoughts on “>No More Delicious Numbness: Pride, Cookies and Good-Looking Men”

Comments are closed.