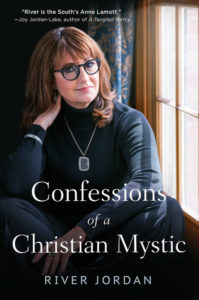

Last year I had the blessing of reading an advance reader’s copy of my friend River Jordan’s new book, Confessions of a Christian Mystic, which will be released on April 2. I knew it was something special, and I can’t wait for it to make its appearance! (Here’s a wonderful review of Confessions of a Christian Mystic by Tina Chambers

Last year I had the blessing of reading an advance reader’s copy of my friend River Jordan’s new book, Confessions of a Christian Mystic, which will be released on April 2. I knew it was something special, and I can’t wait for it to make its appearance! (Here’s a wonderful review of Confessions of a Christian Mystic by Tina Chambers

Over at Chapter 16: “Until the World is Full”. )

But today I want to talk about something that River said in this wonderful conversation she had with Silas House which was just published by Parnassus Books on their site, Musing:

The Holy Ground of Story: A Conversation Between Silas House and River Jordan

The whole conversation is wonderful—I especially like what she says about art and music not having to be “religious” to be part of what she calls “the holy ground of story”—but what I want to focus on today is this:

House asks,

“In the book you talk about how the word “Christian” is so loaded these days. . . . What do you say to the people who might hesitate reaching for this book because of that word in the title?”

I was on the edge of my seat to read River’s response to this, because I often post things in my blog or on social media that might be considered “loaded” in that they are unapologetically filled with not only spiritual terminology, but also words that are strongly religious, and specifically Christian. And in a more specific “subset,” Orthodox Christian. So here’s what River said in answer to House’s question:

“I hope people will at least pick it up to peruse, discover it is a fusion of faith and fiction and essay and fall in love with the strange little genre-buster that it is.”

That’s what I hoped from the beginning for my novel Cherry Bomb. It’s not a genre-buster like Confessions—it’s a straight-up southern literary novel. But it’s infused with a (strange?) mix of sexual abuse, a religious cult, graffiti, Orthodox Christianity, abstract expressionist art, and weeping icons. I hoped (and still hope) for a readership beyond those who typically read Christian fiction, which Cherry Bomb is not. River addresses some of these same issues as she continues to answer House’s question:

“In the bigger picture, it occurs to me that many of us are not talking about our faith very much. We’re talking about great stories and music, fiction and movies, and where the greatest new Thai restaurant is; but apparently the conversation that features the Christian faith as we know it to be true is not part of our cultural mainstream. If it were, we wouldn’t cringe at the word or have need to defend it.”

Our “cultural mainstream” embraces the word “spiritual” with open arms—arms open wide enough to let in a wide diversity of beliefs, Christian or otherwise. But the word “religious” which seems to invoke a smaller and often maligned following, calls up a more legalistic image. What do you think of when you hear the word “religious”? What do you mean when you say or write it?

In this article from the Huffington Post a few years ago, Shahram Shiva—a longtime Rumi expert—defines a “religious” person in a fairly traditional manner, basically as one who follows the traditions of an established religion—Christian or otherwise. But then he limits his definition of a “spiritual” person to exclude people who are religious, offering this simple “test” to determine which camp we fall into:

It’s very easy to discover if you are religious or spiritual.

1. Do you worship any type of a deity or a God or a sect leader? This includes popular yoga gods such as Ganesh or Rama and so called gurus or masters. Then you are religious.2. Do you believe in the power of your own self and that you are in charge of your destiny? In this case you are spiritual.

Shiva’s definition of a spiritual person excludes Christians, or others who worship any type of deity. And yet for centuries the Orthodox Christian Church—the faith that I follow—has held up their theologians as being “spiritual.”

The Greek Orthodox theologian Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos, writes about these terms in “The Difference Between Orthodox Spirituality and Other Traditions”:

“Orthodox spirituality differs distinctly from any other “spirituality” of an eastern or western type. There can be no confusion among the various spiritualities, because Orthodox spirituality is God-centered, whereas all others are man-centered.”

Shiva would agree with Vlachos, since he says that a spiritual person believes in “the power of your own self.”

I wonder what Shiva thinks about the thousands of Orthodox Christians who follow the teachings of their Church on Orthodox spirituality? I love this article, “Orthodox Spirituality,” which appears on the website of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA). Here’s a short quote:

I wonder what Shiva thinks about the thousands of Orthodox Christians who follow the teachings of their Church on Orthodox spirituality? I love this article, “Orthodox Spirituality,” which appears on the website of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA). Here’s a short quote:

“Spirituality in the Orthodox Church means the everyday activity of life in communion with God. The term spirituality refers not merely to the activity of man’s spirit alone, his mind, heart and soul, but it refers as well to the whole of man’s life as inspired and guided by the Spirit of God.”

During Great Lent Christians focus on having our lives “inspired and guided by the Spirit of God” in a more dynamic way. It’s not that we only want to live this way for 40 days before Pascha (Easter) every spring. But sometimes during the other 325 days we lose a bit of steam and need our engines fired back up. I want to live a more “spiritual” life every day, but of course I fall short of my goals and repent and receive forgiveness and grace over and over. And all of this takes place within the walls–physical and spiritual—of my Church, and the religion it represents.

You can see River’s calendar of events on her tour for Confessions here, starting with her launch at Parnassus in Nashville on March 29. I’m excited that she will be here in Memphis on April 25, at Novel Books. Can’t wait to visit with her about all things mystical, spiritual, artistic, and yes, religious.