Never has the world needed a peacemaker more than today. We need a peacemaker to settle the wars in the Middle East. We need a peacemaker to keep us from a new war with North Korea. We need a peacemaker in our cities and communities to help prevent the growing mass murders and acts of terrorism. We need a peacemaker to help families mend and prevent domestic violence. We need a peacemaker to tame the wolf.

This morning I read the following excerpt on Facebook. It’s from Jim Forest’s book, The Ladder of the Beatitudes. I haven’t read this book, but I loved his book Praying With Icons. I’m reprinting the excerpt about St. Francis here with the author’s permission. I hope lots of people read this and share St. Francis’ message of peace, courage, faith, hope, and love.

This morning I read the following excerpt on Facebook. It’s from Jim Forest’s book, The Ladder of the Beatitudes. I haven’t read this book, but I loved his book Praying With Icons. I’m reprinting the excerpt about St. Francis here with the author’s permission. I hope lots of people read this and share St. Francis’ message of peace, courage, faith, hope, and love.

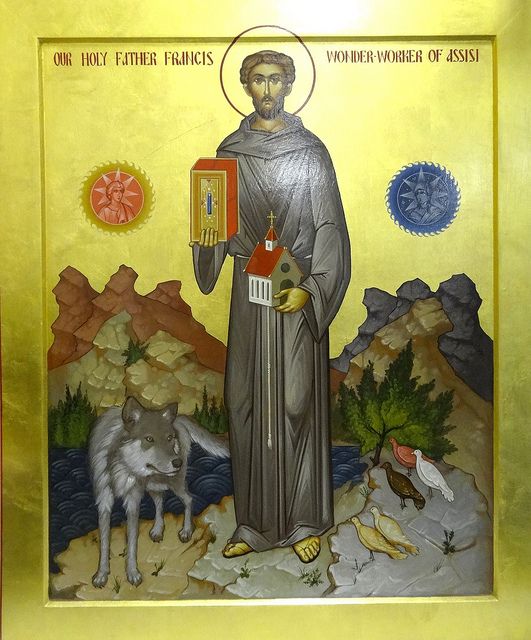

Today is the feast of St Francis. He was born in Assisi, in central Italy, in 1182. He started out as a wealthy man-about-town until he fell into a serious illness in his 19th year. He was praying in the dilapidated Church of St. Damiano one day in 1206, and he heard the voice of Christ saying, “Go, Francis, and repair my house which, as you see, is fallen into ruin.”

One of the stories of his many efforts as a peacemaker comes toward the end of his life and concerns Gubbio, a town north of Assisi. The people of Gubbio were troubled by a huge wolf that attacked not only animals but people, so that the men had to arm themselves before going outside the town walls. They felt as if Gubbio were under siege.

Francis decided to help, though the local people, fearing for his life, tried to dissuade him. What chance could an unarmed man have against a wild animal with no conscience? But according to the Fioretti, the principal collection of stories of the saint’s life,

“Francis placed his hope in the Lord Jesus Christ, master of all creatures. Protected neither by shield or helmet, only arming himself with the sign of the Cross, he bravely set out of the town with his companion, putting his faith in the Lord who makes those who believe in him walk without injury on an asp … and trample not merely on a wolf but even a lion and a dragon.”

Some local peasants followed the two brothers, keeping a safe distance. Finally the wolf saw Francis and came running as if to attack him. The story continues:

“The saint made the sign of the Cross, and the power of God . . . stopped the wolf, making it slow down and close its cruel mouth. Then Francis called to it, ‘Brother Wolf, in the name of Jesus Christ, I order you not to hurt me or anyone.”

The wolf then came close to Francis, lowered its head and then lay down at his feet as though it had become a lamb. Francis then censured the wolf for its former cruelties, especially for killing human beings made in the image of God, thus making a whole town into its deadly enemy.

“But, Brother Wolf, I want to make peace between you and them, so that they will not be harmed by you any more, and after they have forgiven you your past crimes, neither men nor dogs will pursue you anymore.”

The wolf responded with gestures of submission “showing that it willingly accepted what the saint had said and would observe it.”

Francis promised the wolf that the people of Gubbio would henceforth “give you food every day as long as you shall live, so that you will never again suffer hunger.” In return, the wolf had to give up attacking both animal and man. “And as Saint Francis held out his hand to receive the pledge, the wolf also raised its front paw and meekly and gently put it in Saint Francis’s hand as a sign that it had given its pledge.”

Francis led the wolf back into Gubbio, where the people of the town met them in the market square. Here Francis preached a sermon in which he said calamities were permitted by God because of our sins and that the fires of hell are far worse than the jaws of a wolf which can only kill the body. He called on the people to do penance in order to be “free from the wolf in this world and from the devouring fire of hell in the next world.” He assured them that the wolf standing at his side would now live in peace with them, but that they were now obliged to feed him every day. He pledged himself as “bondsman for Brother Wolf.”

After living peacefully within the walls of Gubbio for two years, “the wolf grew old and died, and the people were sorry, because whenever it went through the town, its peaceful kindness and patience reminded them of the virtues and holiness of Saint Francis.”

Is it possible that the story is true? Or is the wolf a storyteller’s metaphor for violent men? While the story works on both levels, there is reason to believe there was indeed a wolf of Gubbio. A Franciscan friend, Sister Rosemary Lynch, told me that during restoration work the bones of a wolf were found buried within the church in Gubbio.

Francis became, in a sense, the soldier he had dreamed of becoming as a boy; he was just as willing as the bravest soldier to lay down his life in defense of others. There was only this crucial difference. His purpose was not the defeat but the conversion of his adversary; this required refusing the use of weapons of war because no one has ever been converted by violence. He always regarded conversion as a realistic goal. After all, if God could convert Francis, anyone might be converted.

“They are truly peacemakers,” Saint Francis wrote in his Admonitions, “who are able to preserve their peace of mind and heart for love of our Lord Jesus Christ, despite all that they suffer in this world.”