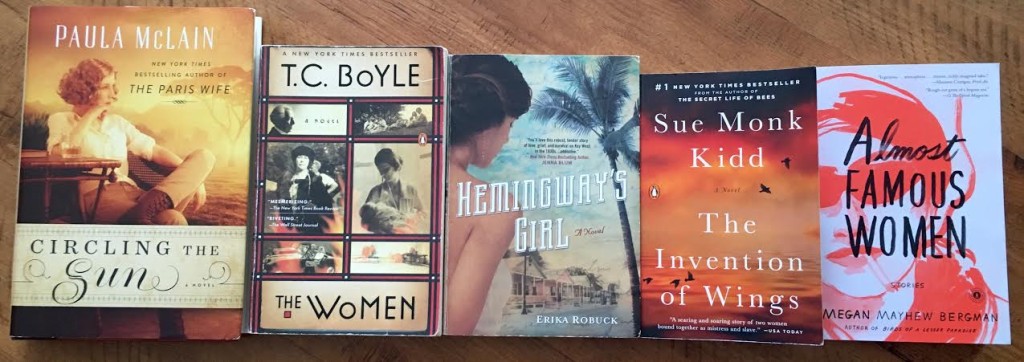

I love books about women whose important contributions to the worlds of art, religion, literature, music, politics, or culture were obscured by their circumstances or by more famous or more powerful men. T. C. Boyle’s The Women tells parts of Frank Lloyd Wright’s story through the lives of his mistresses and wives. In The Paris Wife, Paula McLain sheds light on significant chapters of Hemingway’s career through the eyes of Hadley Richardson; whereas Hemingway’s life in depression-era Key West is colored by a young woman his wife hires as a maid, Marietta Bennet, in Hemingway’s Girl by Erika Robuck. McLain returns to historic fiction with her portrayal of Beryl Markham in Circling the Sun. Sue Monk Kidd’s The Invention of Wings brings the story of Sarah Grimke and her urban slave, Hetty “Handful” Grimke, in early nineteenth century Charleston to modern readers, along with its message of bravery and selflessness which often go unnoticed. And then Megan Mayhew Bergman takes on thirteen women in her story collection, Almost Famous Women—women like Norma, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sister, and James Joyce’s troubled daughter, Lucia. All of these books inspire me to find another courageous woman, lost to history, to resurrect in fiction. (I’m still searching for my heroine.)

Meanwhile, I can’t say enough good things about The Confessions of X, which I just read in just three days. I’m a slow reader and usually only read one to two books a month, but I couldn’t put this one down. Suzanne Wolfe (you might recognize her name from Image Journal, which she publishes and edits with her husband Gregory Wolfe) had me from the start with her subject—“X,” called Naiad in the novel, the concubine of Augustine, the Augustine who would become Bishop of Hippo and would later be canonized. Augustine and the young girl from Carthage with whom he fell in love agreed to a life without marriage, as she was below his station. The book, told through her voice, begins and ends with Augustine’s death and funeral, where her interior monologue tells much of her emotional struggle:

Meanwhile, I can’t say enough good things about The Confessions of X, which I just read in just three days. I’m a slow reader and usually only read one to two books a month, but I couldn’t put this one down. Suzanne Wolfe (you might recognize her name from Image Journal, which she publishes and edits with her husband Gregory Wolfe) had me from the start with her subject—“X,” called Naiad in the novel, the concubine of Augustine, the Augustine who would become Bishop of Hippo and would later be canonized. Augustine and the young girl from Carthage with whom he fell in love agreed to a life without marriage, as she was below his station. The book, told through her voice, begins and ends with Augustine’s death and funeral, where her interior monologue tells much of her emotional struggle:

Many come and the sound of their prayers is sometimes like the thrumming of bees deep within the hive in winter and sometimes like the cry of an animal in the dark. Its ebb and flow sets the leaves shaking and the shadows dancing until it is hard to know what is sorrow and what is joy, what is greeting, what is farewell. Such has been the sound of my life as it has passed along the wide corridors of time to this moment, here in this place, where I will once more look upon his face.

Naiad was the daughter of a mosaic-maker, and she was also his apprentice, working along side him on many projects usually done by young boys. As she thinks back from old age to herself as a girl of ten, her memories become metaphors for her life:

Under the direction of my father who worked by my side, we scrubbed the tesserae with brushes dipped in sand and oil and then rubbed them with leather cloths, smoothing and burnishing until the whole floor shone, my father explaining that any roughness in the surface would catch on sandals, dislodge the tiles, and destroy the mosaic over time. Such polishing we do to our memories so they will not snag on our souls and cause us to stumble.

Wolfe’s prose shines throughout the story, which spans over five decades of fourth and fifth century Corinth, Rome, and Africa. She awakens our senses to each exotic location, like her journey to Thagaste when Augustine’s father was dying:

…the beauty of our first journey is with me still like ephemera of dreams that come unbidden to the mind long after sleep is past…. Seabirds shouldering the following air, cutting and dipping like Icarus gone beneath the cliffs, their cries a paean to their darings; the salt on his lips as we kissed; the dust so thick and choking in the first spring heat, we resembled those sad shades who wander on the nearer shore, no coin to pay the ferryman. We bathed in rivers that ran like molten silver through plotted fields….

And on their return journey to Carthage, after she gave birth to their son, we again feel that we are with them, experiencing the sights, the sounds, the very earth:

The land lay rich and replete as far as the eye could see, the wheat stirring and riffling in the wind, the vines marching in serried ranks to the furthermost distance where terra-cotta tiles glowed among the deepest green of ancient pines like molten honey in the sun.

![Suzanne Wolfe [Photo credit Wolfe-Blevins Photography ]](https://susancushman.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Suzanne-Wolfe-246x300.jpg)

Wolfe makes it clear in her Author’s Note that the book is a work of fiction, and even points out places where she intentionally strayed from the historic account of Augustine’s youth, rise to greatness, and eventual coronation as a bishop. She also gives a modern take on Naiad’s place as Augustine’s concubine, while explaining the background of this ancient practice. (See my post about fictionalizing historic figures for more on this.)

An added benefit for reading groups and book clubs are the 12 discussion questions she offers for readers. The one I found most interesting reflects on Augustine’s great respect for Naiad intellectually and spiritually:

One of the recurring themes in the story is the conflict between “flesh” and “spirit.” Augustine in particular struggles with the nature of the body. Do you think X helps him to change or grow with regard to these issues?

I’ll close with that question, and leave it to you, the reader, to form your own opinions as you avail yourself of this literary treasure. I’m so thankful to have discovered it! Read more in this article by Wolfe about the writing of the book.