“No matter what is wrong with you, a sausage biscuit will make you feel a whole lot better.”—Lee Smith’s mother (p. 39 in Dimestore: A Writer’s Life)

I just finished reading a wonderful book, Dimestore: A Writer’s Life by Lee Smith. It has been several years since I’ve read any of Smith’s novels—The Last Girls being my favorite—but I was drawn to this, her first memoir, because I wanted to know more about her as a writer. Where did all those colorful characters and crazy stories come from? Turns out many of them came from the life all around her in the mountains of Appalachia, where she grew up. But in Dimestore (referring to her father’s store where she spent much of her childhood) she talks about more than just “writing what you know.”

The first time I experienced “author-life envy” was when I heard my friend Neil White tell his story about spending eighteen months incarcerated in the country’s last leper colony. I was writing creative nonfiction at the time, and I wished for a more colorful life. Sure, mine was back-loaded with childhood sexual abuse, eating disorders, struggles with addiction, and seventeen years in a religious cult, but somehow none of that seemed as exciting as Neil’s story. Evidently I’m not the first emerging writer to feel this way, as Lee describes in this scene with one of her writing students:

“…what should I tell my student, one of my very favorite students, who burst into tears after we attended a reading together at which Elizabeth Spencer read her fine short story “The Cousins.” “I’ll never be a Southern writer!” my student wailed. “I don’t even know my cousins!” Raised in a military household, relocated many times, she had absolutely no sense of place, no sense of the past, no sense of family. How did she spend her childhood? I asked. In the mall in Fayetteville, North Carolina, she tearfully confessed, sneaking cigarettes and drinking Cokes.

“I told her she was lucky.

“But she was also right. For a writer cannot pick her material any more than she can pick her parents; her material is given to her by circumstances of her birth, by how she first hears language. “ (p. 117)

As I have worked to pen two book-length memoirs and then finally a novel—having chapters of each work critiqued at various writing workshops and in groups—I have often heard the age-old advice, “Write what you know,” batted about by some who agreed and others who didn’t give it much credence. Smith addresses this several places in Dimestore:

“So we have to stop writing strictly about what we know, which is what they always told us to do in creative writing classes. Instead, we have to write about what we can learn, and what we can imagine, and thus we come to experience that great pleasure Anne Tyler noted when somebody asked her why she writes, and she answered, ‘I write because I want more than one life.’” (p. 167)

Although all of my published work to date (thirteen essays) are nonfiction, I can understand Tyler’s desire for “more than one life” better in my efforts at fiction. But whatever the genre, our reasons for laboring with the written word are usually personal. Again, from Smith:

“Peter Taylor once said, ‘I write in order to find out what I think.’ This is certainly true for me, too, and often I don’t even know what I think until I go back and read what I’ve written. My belief is that we have only one life, that this is all there is. And I refuse to lead an unexamined life. No matter how painful it may be, I want to know what’s going on. So I write fiction the way other people write in their journals.” (p. 168)

In today’s literary landscape populated by a growing number of memoirs and fiction “based on facts,” critics are often quick to judge work for being “too personal” or “confessional.” This blog is certainly in danger of those labels, and yet I continue to reveal layers and layers of my own “stuff” here, three times a week, as well as in most of my essays. I found a better understanding of myself, and my own personal writing journey, through more of Smith’s words:

“This is an enviable life, to live in the terrain of one’s heart. Most writers don’t—can’t—do this. Most of us are always searching, through our work and in our lives; for meaning, for love, for home.” (p. 74)

“Now I see this issue—permission to write—as the key issue for many women I have worked with in my classes, especially women who have begun writing later in their lives.” (p. 161)

“No matter what I may think I am writing about at any given time—majorettes in Alabama, or a gruesome, long-ago murder, or the history of country music—I have come to realize that it is all, finally about me, often in some complicated way I won’t come to realize until years later.” (pp. 169-70)

“Writing can also give us the chance to express what is present but mute, or unvoiced, in our own personalities . . . because we are all much more complicated and various people than our lives allow.” (pp. 174-5)

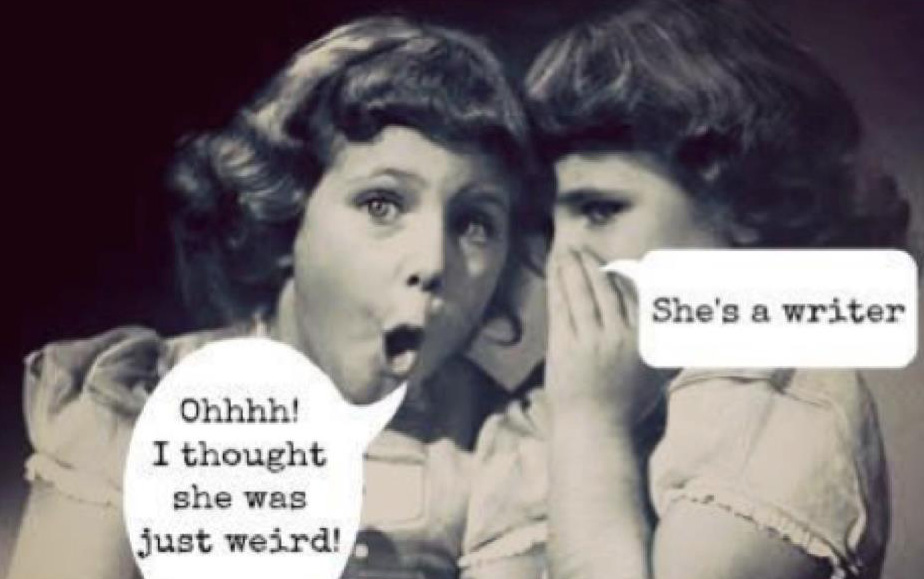

I’ll close with some inspirational words about the emotional pleasure Smith gets from writing—something most writers can identify with, even when our friends and family might think we’re a bit crazy:

“Writing is also my addiction, for the moment when I am writing fiction is that moment when I am most intensely alive. This ‘aliveness’ does not seem to be mental, or not exactly…. I feel a dangerous, exhilarating sense that anything can happen.” (p. 170)

“For me, writing is a physical joy. It is almost sexual—not the moment of fulfillment, but the moment when you open the door to the room where your lover is waiting, and everything else falls away.” (p. 171)