One thing I find helpful about Facebook is the groups that form around common interests and pursuits. I belong to several of them, one of which is for memoir writers. Another specifically for essayists. Others for fiction writers, and so on. One of those groups is run by Sarah Einstein.

One thing I find helpful about Facebook is the groups that form around common interests and pursuits. I belong to several of them, one of which is for memoir writers. Another specifically for essayists. Others for fiction writers, and so on. One of those groups is run by Sarah Einstein.

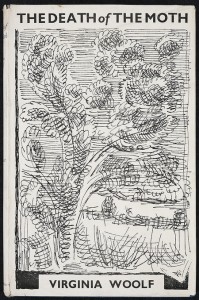

I met Sarah at a Creative Nonfiction Conference about five years ago. The manuscript critique group we were in workshopped an early draft from her memoir, Mot, which just won the 2014 AWP Award for Creative Nonfiction. Here’s a great interview with Sarah, who advises memoirists to “be as naked on the page as possible.” Sarah is now managing editor of Brevity Magazine. She’s a smart writer, so I pay attention when she makes suggestions. Recently she suggested a writing exercise—to read Virginia Woolf’s essay from 1942, “The Death of the Moth,” and consider the questions for discussion and writing at the end. (If you click on the link for the essay you can read the essay and the questions.)

Conduct a Toulmin analysis of Woolf’s essay. What is her claim? What are her reasons to support that claim? What are the warrants that underlie the claim?

My younger self might have answered these questions quite differently—possibly with some undertones of anger and sarcasm—with trite exclamations such as, “life sucks, then you die.” Woolf’s essay was published a year after her death by suicide, but I don’t know when it was actually written. I imagine she penned it closer to the time of her death than during her youth. Her claim was that nothing has any chance against death. She supports that claim not only with the image of the short life of the (one-day) moth, but also with reminders that the same energy that sends the moth fluttering against the window pane also “inspired the rooks, the ploughmen, the horses, and even, it seemed, the lean bare-backed downs.” The warrants that underlie the claim are the undisputed facts about the moth’s limitations:

“That was all he could do, in spite of the size of the downs, the width of the sky the far-off smoke of houses, and the romantic voice, now and then, of a steamer out at sea. What he did do he did. Watching him, it seemed as if a fiber, very thing but pure of the enormous energy of the world had been thrust into his frail and diminutive body. As often as he crossed the pane, I could fancy that a thread of vital light became visible. He was little or nothing but life.”

Next question:

What is Woolf’s purpose in writing this essay? To explore? Inform? Convince? Meditate or pray?

On a second and a third reading of the essay, I can find several of these purposes in Woolf’s essay. She explores the nature of the day moth’s life and informs the reader of her discoveries from her observation. I don’t feel an urgency on her part to convince, and nowhere do I find any efforts towards prayer. Meditation? Possibly. At a minimum a serious reflection.

Why has this essay endured for sixty years? What makes it memorable, lasting?

Beyond the exquisite beauty of the words themselves, the essay accomplishes something larger than the writing, something beyond the prose. Woolf, through her powers of observation and ways of seeing that so many lack, takes a larger image of the world and life and death and nature and joy and sadness and refines that image down to the humble life and death of a creature that only lives for twenty four hours:

Beyond the exquisite beauty of the words themselves, the essay accomplishes something larger than the writing, something beyond the prose. Woolf, through her powers of observation and ways of seeing that so many lack, takes a larger image of the world and life and death and nature and joy and sadness and refines that image down to the humble life and death of a creature that only lives for twenty four hours:

“The possibilities of pleasure seemed that morning so enormous and so various that to have only a moth’s part in life, and a day moth’s at that, appeared a hard fate, and his zest in enjoying his meager opportunities to the full, pathetic.”

And yet she found something beautiful, something to celebrate, even in this pathetic little life:

“It was as if someone had taken a tiny bead of pure life and decking it as lightly as possible with down and feathers, had set it dancing and zigzagging to show us the true nature of life.”

It’s a short essay. If you are an avid reader, you will benefit from its reading. If you are a writer, you can learn much from this short exercise. Thanks for sharing it, Sarah.