After completing my second (non-fiction) memoir—and turning down a New York agent’s request for the manuscript because I realized I didn’t want to go public with the book—I turned to fiction in 2010 and began to write a novel, Cherry Bomb. Several agents are reading the manuscript now (fingers and toes crossed) and while I’m waiting, I’m reading about trends in the worlds of fiction and nonfiction.

After completing my second (non-fiction) memoir—and turning down a New York agent’s request for the manuscript because I realized I didn’t want to go public with the book—I turned to fiction in 2010 and began to write a novel, Cherry Bomb. Several agents are reading the manuscript now (fingers and toes crossed) and while I’m waiting, I’m reading about trends in the worlds of fiction and nonfiction.

William Deresiewicz, states in his article in The American Scholar, “Fiction’s Revenge,”

“The very idea of fiction is relatively recent. Traditional societies didn’t have it, and when it arose, couldn’t wrap their heads around it. Homer’s audience thought he was writing history. 2,500 years later, Robinson Crusoe was presented as a true story; no one would have cared about it otherwise. Only slowly through the 17th and 18th centuries did the notion emerge that a story could be meaningful without being factual, that between or beside truth and falsehood lies a third category, where something can be realistic without being real, referential without referring to actual events, believable without attempting to evoke belief.”

Meaningful without being factual. Realistic without being real. Believable without attempting to evoke belief. My first response to these words was “of course good fiction does these things.” But his words gave me pause, and I began to consider why—why write (or read) fiction rather than nonfiction? Can’t good creative nonfiction (like a good memoir or essay) achieve these ends?

Rod Dreher, in his article, “Fiction Cannot Die,” says:

“The main reason I read at all is because I have a deep curiosity about the world, and want to learn more. I concede that fiction at its best is not an escape from the world, but rather an indirect mode of engaging it, and in that sense a different way of learning about it than directly, through non-fiction.”

Where Dreher reads out of a deep curiosity about the world, I think I read (and write) in order to make sense of the world, and myself. Rather than reading to gain more information, I think I read to understand what I already know, but on a different level. Which is why I tend to read more memoirs than any genre. Good memoirs reveal what I’m longing to know—not just the facts about someone’s life, but the emotional impact the events of their life have had on them. Whether they suffered horrific injustices and somehow rose above them (or not) or whether they gained some new insight through their experiences, I’m eager to read about it. I prefer memoir to straight biographies (or autobiographies) for this very reason—I want more than the facts. I want art.

Art? Sure. But not just any kind of art. I am a huge fan of abstract art. While I can appreciate the talent required for an artist to lay down a brilliantly accurate work of realism—and I know there is art involved, not just craft—I am moved in a different way by the artist’s expression in an abstract work. This explains why I’m so drawn to Coptic icons (which feature in my novel) with their simple, almost cartoonish features, more so than traditional Byzantine icons. (It’s not that I don’t love the Byzantine icons, too—and I’ve painted about 50 of them—but the execution of them feels more like craft than art.)

Art? Sure. But not just any kind of art. I am a huge fan of abstract art. While I can appreciate the talent required for an artist to lay down a brilliantly accurate work of realism—and I know there is art involved, not just craft—I am moved in a different way by the artist’s expression in an abstract work. This explains why I’m so drawn to Coptic icons (which feature in my novel) with their simple, almost cartoonish features, more so than traditional Byzantine icons. (It’s not that I don’t love the Byzantine icons, too—and I’ve painted about 50 of them—but the execution of them feels more like craft than art.)

I’m not a snob. I enjoy and appreciate many forms of entertainment that aren’t “high art.” I enjoy soapy television dramas, chick lit (yes, this can come in literary or non-literary form), and the occasional legal thriller. But my enjoyment of those forms has more to do with a casual perusal than an intellectual, or artistic, study.

My favorite novels and memoirs have delivered both—the quick entertainment fix and a deeper, slower, artistic element. Maybe there’s a new sub-genre on the rise. Or maybe these books (and televisions shows and movies) fit into a genre I recently saw listed on a literary agent’s web site—high-end commercial. And on another site—high concept plot.

Texas poet, short story author and novelist, Annie Neugebaur, thinks so, as she says in her post from this past July, “What is Commercial Fiction?” She discusses some differences in the style and genre of commercial and literary fiction, but ends by saying:

“I think we’ve all witnessed lit-fic and commercial fiction fans throwing tomatoes at each other over the years, but the truth is that no one is ever going to win the big fight. And the reason for that is simple: both types of literature have their own value for different tastes and different readers at different points in their lives. Why does one have to win? Why do they even have to be pitted against each other? At the end of the day, they both belong in the same realm: literature.”

Why do these terms even matter? I’m being asked to categorize my novel when I query literary agents, and usually I say “literary,” but sometimes I say, “high-end commercial,” or “women’s fiction.” I wish there was a category that just says “kick-ass, artistic fiction.” Maybe that’s too self-serving. I’m afraid to say “chick lit” because it’s gotten such a bad rap recently. AgentQuery.com tries to define all these genres for the emerging author. Sometimes they blur the lines, and sometimes they over-simplify:

Why do these terms even matter? I’m being asked to categorize my novel when I query literary agents, and usually I say “literary,” but sometimes I say, “high-end commercial,” or “women’s fiction.” I wish there was a category that just says “kick-ass, artistic fiction.” Maybe that’s too self-serving. I’m afraid to say “chick lit” because it’s gotten such a bad rap recently. AgentQuery.com tries to define all these genres for the emerging author. Sometimes they blur the lines, and sometimes they over-simplify:

“Unlike chick lit, women’s fiction often delves into deeper, more serious conflicts and utilizes a more poetic literary writing style.”

Really? So nothing they call “chick lit” can have literary value? I’m not sure I agree. Cassandra King’s 2002 novel, The Sunday Wife (categorized as chick lit) definitely kicks ass with her literary prose, depth of discovery, rich characters, and strong sense of place.

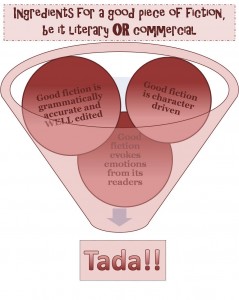

AgentQuery.com says this about commercial fiction:

“Like literary fiction, the writing style in commercial fiction is elevated beyond generic mainstream fiction. But unlike literary fiction, commercial fiction maintains a strong narrative storyline as its central goal, rather than the development of enviable prose or internal character conflicts.”

The lines seem kind of blurred to me. Can’t literary fiction maintain a “strong narrative storyline” while developing “enviable prose” and “internal character conflicts”? I think some of my favorite novels do this, like Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, Pat Conroy’s The Prince of Tides, and T. C. Boyles’ The Women.

The lines seem kind of blurred to me. Can’t literary fiction maintain a “strong narrative storyline” while developing “enviable prose” and “internal character conflicts”? I think some of my favorite novels do this, like Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, Pat Conroy’s The Prince of Tides, and T. C. Boyles’ The Women.

I want it all. I want my own writing to deliver all of those elements. Am I shooting too high? We’ll see….

I hear you, Susan. I find most writers cross genres at some point. We do ourselves a great injustice to pigeonhole our writing into one solitary category. In my opinion. Besides, the more you study it, the more fuzzy it becomes. I’ve heard different definitions for literary and commercial from several “experts” within the industry.

Personally, I like kick-ass, artistic fiction. That’s perfect.

Thanks for reading… and for validating my “kick-ass, artistic fiction” genre, Pamela.

Categories of literary vs. pop fiction are probably much more useful to the booksellers than to the writer who is telling a story. As a reader I will admit the categories sometimes help me find my way to what I want in the big box book stores….

I must check out the Deresiewicz article– as you are so fond of memoir, I must suppose you’ve read his A Jane Austen Education? Loved that one! Also Michael Chabon’s Maps and Legends is well worth a look.

I haven’t read A Jane Austen’s Education, but it’s on my list now. Also Maps and Legends. So many books….