Every writer, like everybody else, thinks he’s living through the crisis of the ages. To write honestly and with all our powers is the least we can do, and the most.

―Eudora Welty, On Writing

I wrote John and Mary Margaret while isolated during the Covid_19 virus pandemic in the spring and summer of 2020. And yes, I thought I was “living through the crisis of the ages,” as Miss Welty wrote. Parallel to the health crisis was the growing social unrest in our country as protests erupted nationwide in response to the killing of unarmed Black men by white police officers. Of course this inequality isn’t anything new in our country. The mistreatment of Blacks in America started in the 1500s, when the first African slaves were brought to what would become South Carolina.

I was born in Jackson, Mississippi in 1951 and came of age in the 1960s Jim Crow South. Growing up in a privileged white bubble that included a full time Negro maid—as they were called then—summers by the pool at the all-white country club, and walking to my all-white elementary school in our all-white neighborhood. I graduated from high school in 1969, with less than a dozen African American students in our school of over 1,200. The following year busing would change the landscape of our historically segregated education system in Jackson and other parts of the south forever. My first cousin John Jones, who was a few years behind me in high school, edited a book that recounts that story: Lines Were Drawn: Remembering Court-Ordered Integration at a Mississippi High School (Jackson, Mississippi, University Press of Mississippi, 2016). But I missed that experience, as I left home to enter the University of Mississippi as a freshman in 1969.

While researching the events that happened on the Ole Miss campus in the 1960s, I was surprised to learn about the protest at Fulton Chapel in February of 1970 during an “Up With People” concert. I asked my husband and several other students from that year, and very few even remember the event. None of us were even aware of the protest. The injustices that were happening to minorities at my school were not even on my personal radar. My “awakening” to these issues wouldn’t begin in earnest for several years.

In the 1980s my husband and I adopted two children from South Korea. And while they both experienced a degree of discrimination growing up in Jackson, Mississippi and Memphis, it wasn’t until our Korean daughter married an African American man in 2011 and blessed us with two beautiful mixed-race granddaughters in 2012 and 2015 that I began to consider how their lives might be affected by injustices and attitudes about race. After writing this book, I dedicated it to all four of our amazing mixed-race granddaughters. (Two are Korean-African American and two are Korean-Hmong American.)

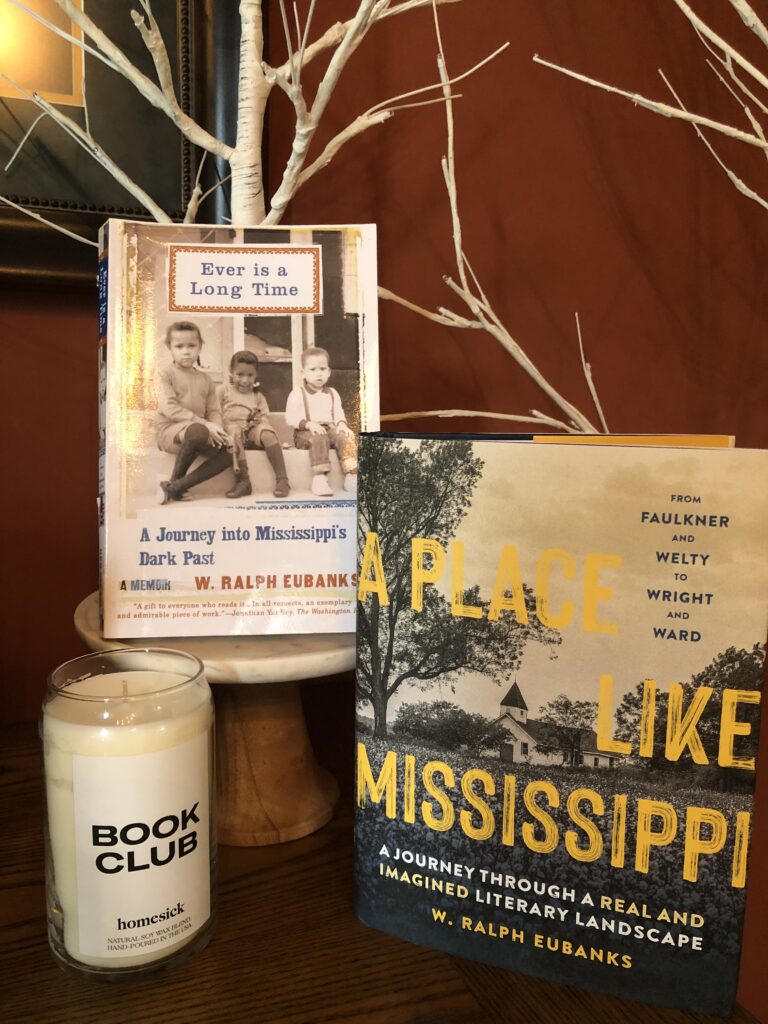

In 2018 I edited a collection of essays by twenty-six southern authors, Southern Writers on Writing, which was published by the University Press of Mississippi. During the process of inviting authors to contribute essays, I quickly realized how few Black authors I knew personally. Through connections with other writers, I was introduced to four, including Ralph Eubanks, a Mississippi native, Ole Miss graduate, and visiting professor. His essay, “The Past is Just Another Name For Today,” opened the door to my latent awakening to the part I have played in allowing my state—and my country’s—blatant caste system to continue to exist.

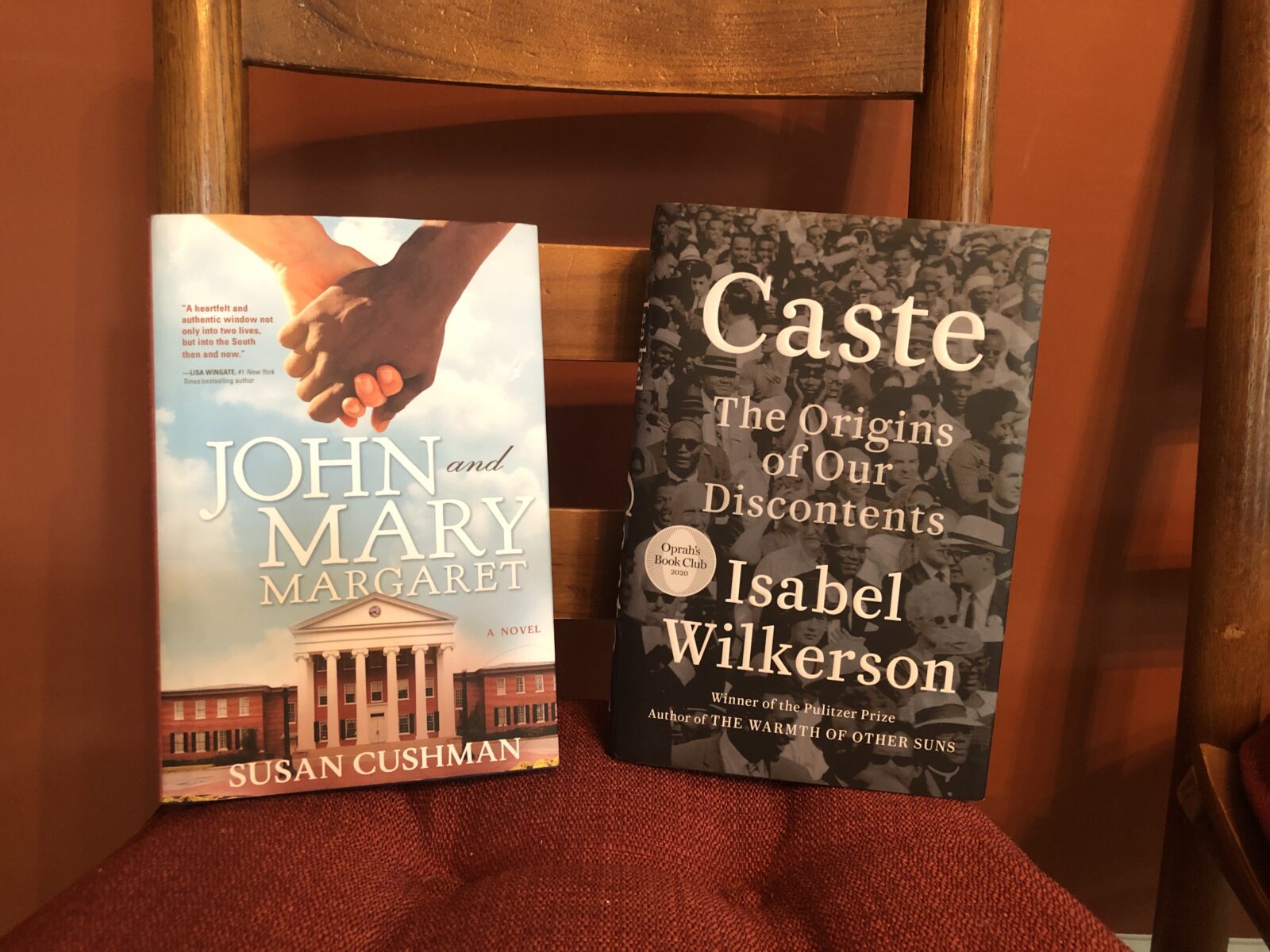

If you are wondering about my use of the words, “caste system,” to describe our nation’s racial structure, let me introduce you to the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson and her profound book, Caste( Random House, 2020). Caste was released in August of 2020, just as I was putting the finishing touches on my first draft of John and Mary Margaret. Reading it was a master class in the history of caste—and race—in America, India, and Nazi Germany. And hopefully, it is helping me continue my “awakening.” As Wilkerson says, of the abolitionists, civil rights workers, and the rare politicians who stood against slavery and the subsequent injustices minorities suffered and continue to suffer:

These are people of personal courage and conviction, secure within themselves, willing to break convention, not reliant on the approval of others for their sense of self, people of deep and abiding empathy and compassion. They are what many of us might wish to be but not nearly enough of us are. Perhaps, once awakened, more of us will be.

This is indeed what I wish to be, a person “of personal courage and conviction.” And according to Wilkerson, becoming that person is a choice:

A caste system persists in part because we, each and every one of us, allow it to exist—in large and small ways, in our everyday actions, in how we elevate or demean, embrace or exclude, on the basis of the meaning attached to people’s physical traits. . . . Once awakened, we then have a choice. We can be born to the dominant caste but choose not to dominate.

Although I wrote this book before reading Caste, I hope and pray that its message will inspire and encourage others to make brave choices, as Albert Einstein did when he escaped the Nazis in Germany and arrived in America in 1932, only to discover that our caste system was just as bad, if not worse. As Wilkerson writes in Caste, Einstein felt that he could “escape the feelings of complicity in it only by speaking out.” I offer John and Mary Margaret as a small but earnest beginning. This is me speaking out.

Author’s Note

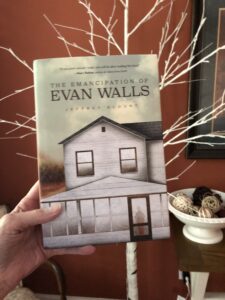

NOTE: Much of this essay became part of the Author’s Note in the back of JOHN AND MARY MARGARET. I share it here to expand on what I wrote there, and to encourage those who haven’t bought and read the book to please do so. And if you are interested in reading more about race in America, check out my “Black History Month Reading List,” from February. I know I mentioned Ralph Eubanks in the above essay, but I’d also like to mention Jeffrey Blount. Both of these African American authors were early readers for JOHN AND MARY MARGARET and have continued to support me and the book by joining me in conversation for virtual events at Novel Books in Memphis and Lemuria Books in Jackson, Mississippi. I am so grateful for their wisdom, inspiration, and friendship.

I am a 78 year old native of Atlanta Georgia. I had not planned to read your book,”John and Mary Margaret” until I read the above biography. You saw the effects racism can have on people just as I did. I was a student at Georgia State University in downtown Atlanta during the lunch counter sit-ins and the marches for justice by Dr. Martin Luther King. I chose to stay removed from it all until, later, working as an X-Ray Technician, Dr. King was a patient in our department. He waited patiently while the other girls constantly moved his chart to the back of the line, announced that they would refuse to call “Dr.”, and derided the decision to award him the Nobel Peace Prize. I am ashamed that I was not strong and brave enough to defy them. Our chief technician finally took his films. I was in the presence of greatness and let the other girls make my value judgements for me. I began a lifelong determination to treat all people as equals.

Oh, wow, Carol. This is amazing. Thank you SO MUCH for reading JOHN AND MARY MARGARET and sharing this story. My “awakening” is a work in progress. Bless you!