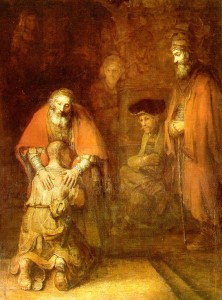

Last Sunday Father Philip Rogers, Assistant Pastor at St. John Orthodox Church in Memphis, gave a wonderful homily. It was the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, and Father Philip reminded us of God’s love. Sounds simple, and it is. Simple to understand but often difficult to actively believe in a way that affects our lives on a daily basis. As Father Philip said (about God’s love for us):

Last Sunday Father Philip Rogers, Assistant Pastor at St. John Orthodox Church in Memphis, gave a wonderful homily. It was the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, and Father Philip reminded us of God’s love. Sounds simple, and it is. Simple to understand but often difficult to actively believe in a way that affects our lives on a daily basis. As Father Philip said (about God’s love for us):

We are supposed to accept it and reflect it back.

(You can listen to Father Phillip’s homily here. And also Father John Troy Mashburn’s wonderful homily from the Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee here.)

Of course the prodigal son didn’t reflect back his father’s love when he chose to ask for his inheritance early and leave home and live a life of wallowing in the mud. But his father loved him so much he allowed his son to make those choices. And of course he forgave and welcomed him home with open arms when his son “came to himself.”

But the thing that brought tears to my eyes during Father Phillip’s homily was the way God treated the thief on the cross. How difficult it is for us to rejoice when God treats with kindness and forgiveness those who have hurt us personally. Or those who have hurt someone we love. I found myself thinking about several people in those categories on Sunday. I thought about the forgiveness I struggle to give. And I wondered why it is so damn hard.

But the thing that brought tears to my eyes during Father Phillip’s homily was the way God treated the thief on the cross. How difficult it is for us to rejoice when God treats with kindness and forgiveness those who have hurt us personally. Or those who have hurt someone we love. I found myself thinking about several people in those categories on Sunday. I thought about the forgiveness I struggle to give. And I wondered why it is so damn hard.

Then on Monday I read Father Stephen Freeman’s article in “Glory to God For All Things,” “It’s a Crying Shame.” The shame Father Stephen writes about here is what we feel when struggle to forgive those who have hurt us. As he says, “…forgiveness is perhaps the most difficult spiritual undertaking. I believe the reason for this is clear: to forgive is to endure shame.”

Why does forgiving sometimes cause us shame? Father Stephen explains:

The experience of shame (how I feel about who I am) is easily the most vulnerable point of encounter in our lives…. Any foray that another makes into the territory of who we are will immediately provoke a defensive response (in one form or another). Encounters that shame us are deeply provocative. It is in this vein that actions requiring forgiveness involve shame. Everything that we experience as a sin against us, is an action involving shame. The shame is the source of its power and is the engine of our protective efforts. To forgive is to drop our guard and expose the nakedness of our selves.

It’s not so hard to forgive when someone acknowledges their sin against you and genuinely asks for forgiveness. But when they don’t—or even when they disagree about an event or they are even unaware that they hurt someone—that’s when shame comes in. Because to forgive them when they don’t ask for it feels like giving in. It feels dishonest. It feels like letting go of something that we feel is “right” in order to humble ourselves and forgive.

It’s not so hard to forgive when someone acknowledges their sin against you and genuinely asks for forgiveness. But when they don’t—or even when they disagree about an event or they are even unaware that they hurt someone—that’s when shame comes in. Because to forgive them when they don’t ask for it feels like giving in. It feels dishonest. It feels like letting go of something that we feel is “right” in order to humble ourselves and forgive.

I think this is a process. Maybe I can focus on this during Great Lent this year. I’m so thankful for the Church’s wisdom in organizing the themes of the Triodion (three Sundays before Lent) to help us get ready. It’s so counter intuitive to move past the shame into a spirit of humility. Lord have mercy.

Thank you so much, Susan. I needed to know I’m not alone!

We’re all walking this path, aren’t we, Diana? Thanks for reading.