Orthodox Christian Mysticism

In my previous post, “Female Mystics, Part I,” I wrote about female mystics in the Episcopalian, Catholic, and Protestant traditions. In Part II I will share a bit about the Orthodox Christian Chuch’s views on mysticism, and a few Orthodox female mystics.

Before I can write about Orthodox female mystics, I need to give an Orthodox Christian definition of mysticism. While there are many sources on the subject, one I find easily relatable is this podcast by Hieromonk Irenei Steenberg, the founder of Monachos.net, on “Orthodoxy and Mysticism” from Ancient Faith ministries. He begins by saying, “Life in Christ is a mystery.” And then after relating numerous stories, he begins his conclusion with these words:

“Mysticism, as Orthodoxy might appropriate the term, has to mean the struggle to gain the experience, the encounter in Christ with the eternal kingdom of God.” To me this means that mysticism isn’t just for those in a special category of sainthood; it’s for all who seek to be united with Christ.

Mysticism and Orthodoxy Theology

Another Orthodox writer, Vladimir Lossky, says, “The eastern tradition has never made a sharp distinction between mysticism and theology; between personal experience of the divine mysteries and the dogma affirmed by the Church.” Again, it seems to me that this experience is accessible for all who would seek it. Lossky continues, “If the mystical experience is a personal working out of the content of the common faith, theology is an expression, for the profit of all, of that which can be experienced by everyone.”

Where Do the Women Come In?

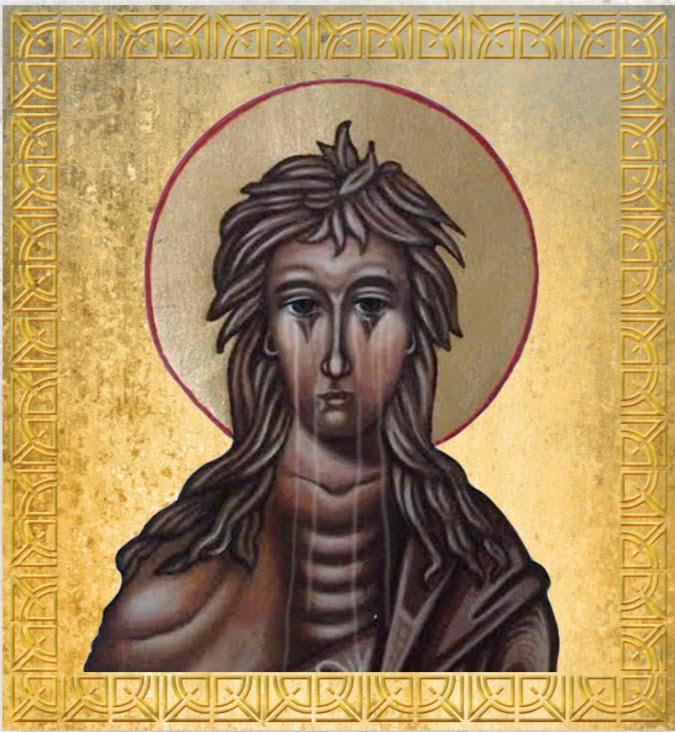

Father George Gray writes about “Mysticism, Women, and the Christian Orient”: When reading Eastern Christian literature, one may occasionally encounter the classification of “mystic” but this title is usually found in conjunction with other descriptive characterizations of the person. A few such “mystics” come to mind: St. Anthony the Great, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Macrina, Pseudo-Dionysius, St. Mary of Egypt, St. Maximus the Confessor, St. Symeon the New Theologian, St. Gregory Palamas, St. Sergius of Radonezh, St. Seraphim of Sarov, among others, were known to have had “mystical experiences. Notice that he includes two women in this “short list”–St. Mary of Egypt (my patron) and St. Macrina.

I’ve written about St. Mary of Egypt many times here on my blog. If you’d like a taste, I suggest these two posts:

St. Mary of Egypt: Turning Lead Into Gold (from April 2016)

Holy Mother Mary, Pray to God For Us (from March 2015)

And of course I tell Mary of Egypt’s story in my novel Cherry Bomb, in which an icon of St. Mary of Egypt weeps.

Contemporary Orthodox Female Mystics

Father Gray writes about several modern-day female Orthodox mystics, including Mother Gavriella Papaiannis: (You can read her inspirational story in the book The Ascetic of Love.)

There was a 20th century Orthodox Christian woman who many consider to be a mystic, if one may use that term. Mother Gavriellia Papaiannis was born in Istanbul in 1897. She entered the monastic life at age 58, after a long career in physical therapy. She served the Church in the Holy Land, Taize, India, East Africa, Britain, America and Greece. Having taken on the obedience of living an active apostolate around the world, Mother Gavriellia fell asleep in the Lord in 1992. Her spiritual children all attest to her sanctity. Many who knew her (and others who have come to know her through her teachings) maintain that she was one of the few “mystics” of the Church – but a mystic whose vocation was in “the world.” Mother Gavriellia has been likened to an eldress in the tradition of St. Macrina. She has been called the Greek Orthodox Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

Another female mystic Father Gray writes about is St. Marie Skobskova of Paris (+1945), “a Russian emigré whose experience of true suffering, her counter-culture “monasticism in the world” and her ultimate sacrifice in Nazi Ravensbruk have proclaimed exactly what it means to be “oned” with God. Her life and witness is best set forth in Sergei Hackel’s Pearl of Great Price.”

Father Gray also asks us to consider Matushka Olga Michael of Alaska (+1979), the Yup’ik village midwife and grandma. Any “mystic” characteristics attributed to her must be coupled with the fact that she often was “invisible” to those around her – simply present in an unassuming manner, but in a manner that was, upon reflection, full of power, grace and the Presence of God. She was the leaven that enlivened the lump of dough. In addition to the stories about her life and death, there have been numerous post-death appearances and healings (collected and recounted in Oleksa and Schimchik) which only underscore the paradox of an extraordinary mystical quality to this seemingly un-extraordinary priest’s wife.

Here’s an extensive list of Orthodox Christian women saints. You can click on each name to read more about each one, and consider for yourself whether or not to call them “mystics.”

In conclusion, I’ll share something Yolanda Robles writes in “Meeting Christian Mystics”:

Of course, in a culture that is increasingly antagonistic to the Christian perspective and lifestyle, the possibility of a distinctly Christian mystical encounter with the Triune God is generally denied. Such an encounter is deemed subjective and individualistic and, therefore, is devalued. As a result, the reliability and credibility of Christian mystics’ personal accounts of their encounters with the divine presence has come under fire. Much skepticism surrounds orthodox Christian mysticism as a whole. Yet in spite of this skepticism, many people today want to understand Christian mysticism. Perhaps they want to counteract the line of thought that calls into question this part of the rich heritage of Christianity and to participate with the mystics in an ineffable encounter with God. However we characterize their motives, those who are delving into a study of Christian mysticism are taking a radically counter cultural stance. Students of mysticism stand in opposition to a society that denies the real presence of God. In recovering this part of Christianity’s legacy, we may yet learn to embody a prophetic stance within the world while at the same time growing in our awareness and love for God.