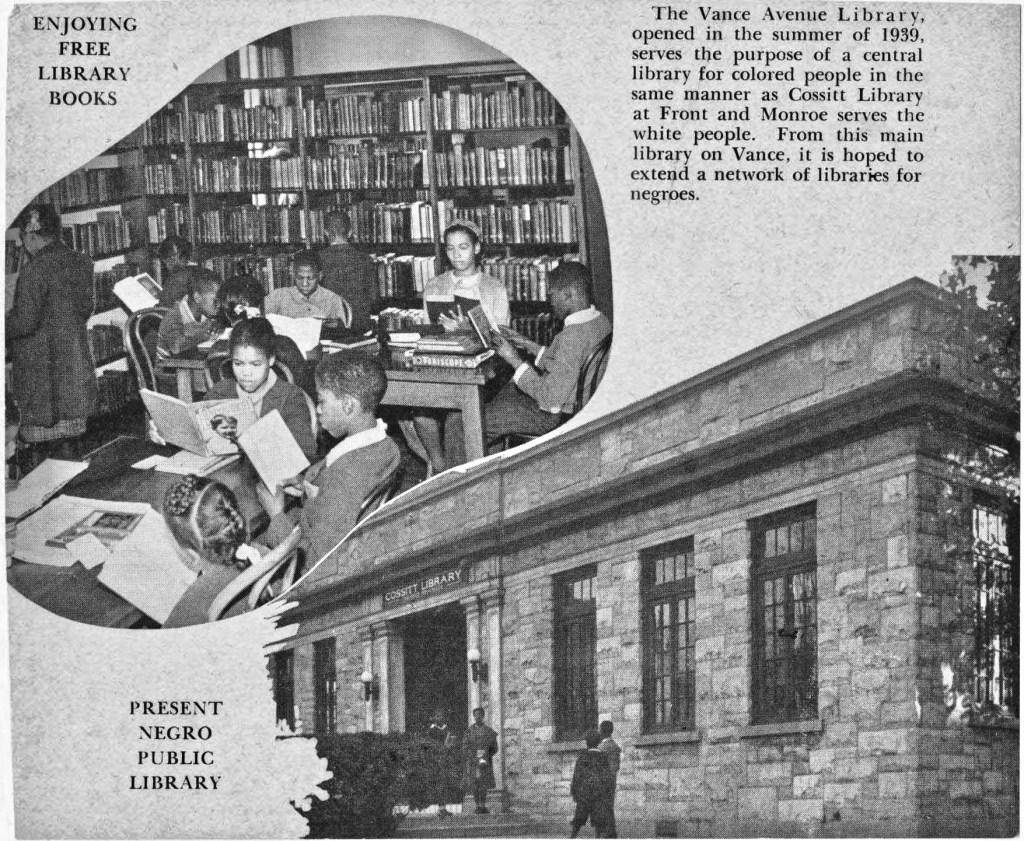

Negro Branches

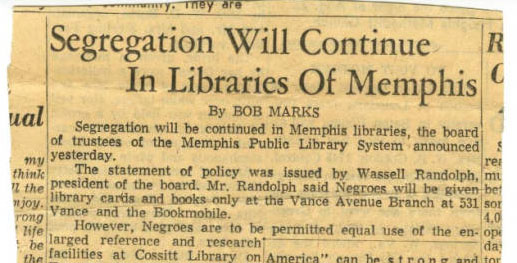

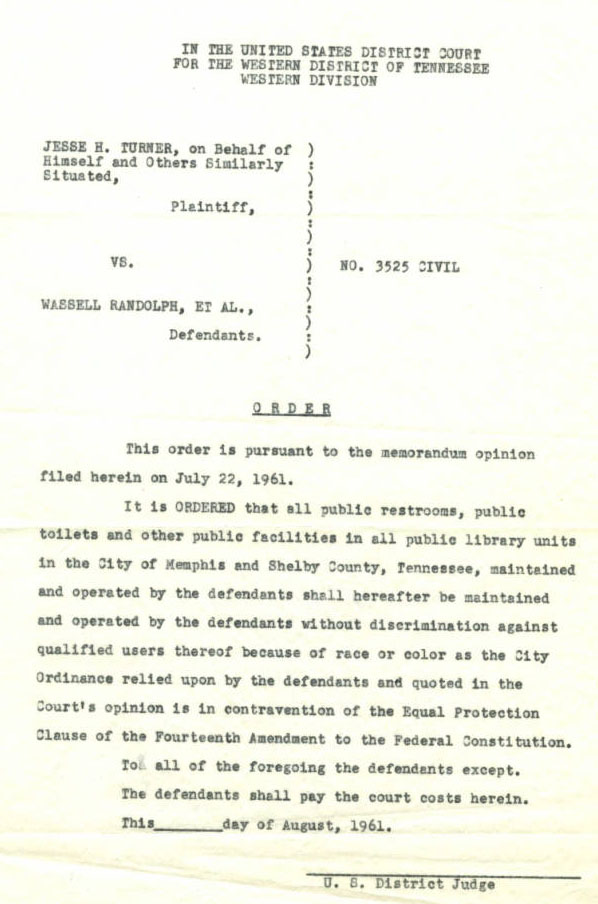

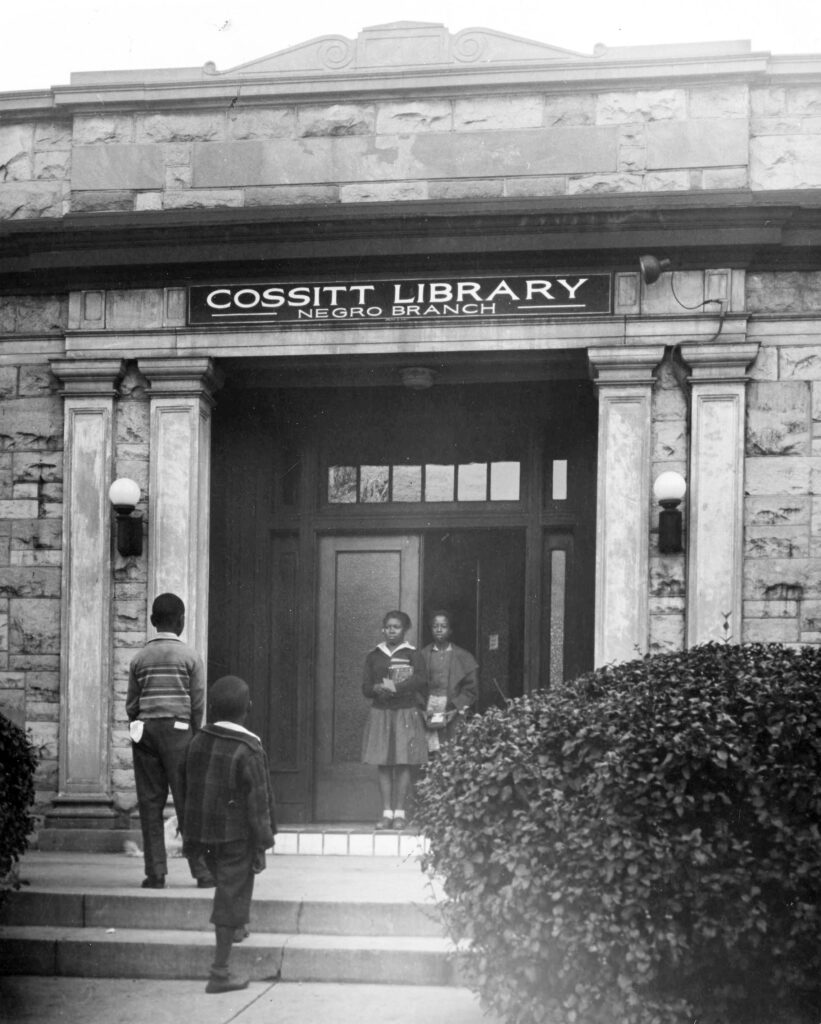

Until 1960, Blacks could only use the Negro branch libraries in Memphis. In my novel JOHN AND MARY MARGARET, John Abbott grew up in Memphis in the 1950s and 1960s and loved reading at an early age. The images here are from newspaper articles and legal documents surrounding the desegregation of libraries in Memphis.

Another Scene from 1963

In my last post, I shared a scene from 1963 in Jackson, Mississippi, about Mary Margaret and her chance encounter with Eudora Welty when she was fourteen. Here’s a “parallel scene” in Memphis, also in 1963, when John was fourteen years old.

Setting the Stage—John’s Family

John grew up in an all-Black neighborhood in Memphis, in the 1950s and 60s. His father, Richard Abbott, was a football coach at the school John attended from ninth through twelfth grades. His mother, Dorothy, was a seamstress who worked from home and did custom ball gown and alterations, mostly for the Midtown society ladies and their daughters. And his older brother Frank, was a natural athlete and a star on the high school football team their father coached. Richard pushed John to follow in Frank’s footsteps, although John preferred to spend his after-school hours at the library. . . . The Reivers was published in 1962, when John was only fourteen. Of course he had no way of knowing it would win the Pulitzer Prize the following year. He just loved the characters. He checked it out over and over at the Cossitt Library downtown. Memphis libraries had only been desegregated in 1960, and John was one of only a few Black kids who frequently used the previously al-White library, which he preferred to the Negro branch libraries around Memphis.

The Scene

One afternoon in the library, he lost track of the time while reading. It was getting dark outside and his mother always warned him about not being downtown too late in the afternoon. Walking out the door onto Front Street, he immediately noticed a group of older White teenagers hanging out at the corner. They saw him, too, and began walking towards him. His bike was on a rack between him and the boys, so he had no choice but to walk towards the bike rack and hope that the boys wouldn’t harass him. He nodded in their direction, as if they were friends, carrying himself confidently and unrushed. As soon as he pulled his bike from the rack one of them shouted, ‘Hey, nigger’! What do you think you’re doing in our library?’

Losing his confidence from a minute earlier, he jumped on his bike and pedaled furiously away just as another boy shouted, ‘You better not have gotten y our cooties all over our books!’

This was something John had not yet experienced in his young life, and it wouldn’t be the last time. It would be years before realizing his dream of becoming a lawyer. Meanwhile, he needed a way to defend himself. Maybe his father’s insistence that he play football wasn’t such a bad idea after all. He was tall for his age and the next couple of years would add some bulk to his slim frame, so he began playing in ninth grade.

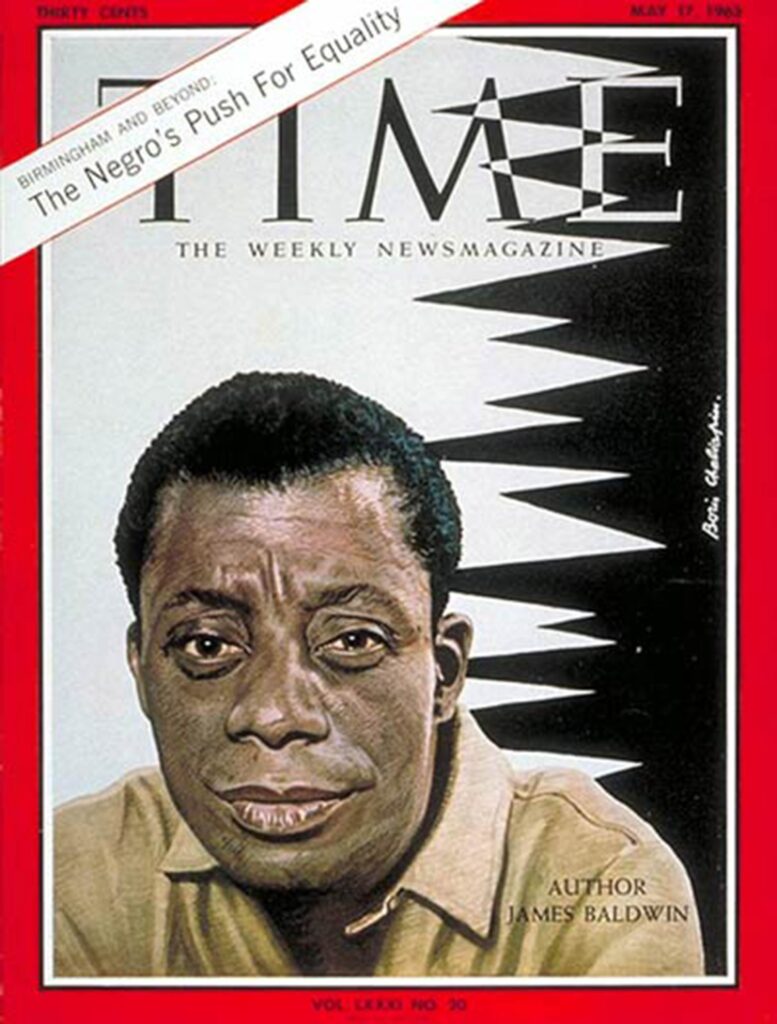

Wisdom from James Baldwin

The chapters in John and Mary Margaret are all introduced with quotes from Southern literary icons and civil rights leaders. I will close with this one:

Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.