I’ve read a number of books by and about Flannery O’Connor, including The Complete Stories, Mystery and Manners, The Obedient Imagination, Flannery, A Life, and others.

I’ve read a number of books by and about Flannery O’Connor, including The Complete Stories, Mystery and Manners, The Obedient Imagination, Flannery, A Life, and others.

And I collect peacocks.

Like this wonderful iron sculpture that welcomes visitors just inside our front door.

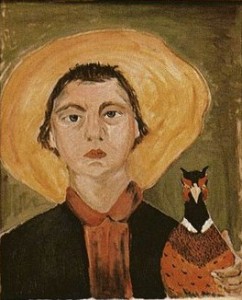

Like O’Connor, I love the symbolism of the peacock—it represents the resurrection and immortality. O’Connor’s self-portrait even includes a peacock. (See picture near the end of the post.)

And then, on a table by my reading chair in my study, I keep a copy of The Habit of Being—Letters of Flannery O’Connor. It was a gift from a dear friend on my birthday in 2007. At that point, I had just finished drafting my first novel (the one in the drawer). My friend wrote this quote from the book under her birthday greeting to me in the front of the book:

And then, on a table by my reading chair in my study, I keep a copy of The Habit of Being—Letters of Flannery O’Connor. It was a gift from a dear friend on my birthday in 2007. At that point, I had just finished drafting my first novel (the one in the drawer). My friend wrote this quote from the book under her birthday greeting to me in the front of the book:

“I find that most people don’t know what a story is until they sit down to write one.”

Five years (and ten published essays) later I find myself picking up the book and reading a few pages at a time for inspiration. I always seem to find something pertinent to my current project. This week’s gleanings include O’Connor’s response to concerns about how her writing would be received by readers. About whether some of her writing would be offensive—to young readers, or sensitive readers, or religious readers. Questions I am currently asking myself about my own novel, as I finish up revisions. At one point O’Connor asked a priest about it. I love his reply:

“You don’t have to write for fifteen-year-old girls.”

And her response:

“Of course, the mind of a fifteen-year-old girl lurks in many a head that is seventy-five and people are every day being scandalized not only by what is scandalous of its nature but by what is not. If a novelist wrote a book about Abraham passing his wife off as his sister—which he did—and allowing her to be taken over by those who wanted her for their lustful purposes—which he did to save his skin—how many Catholics would not be scandalized at the behavior of Abraham? The fact is that in order not to be scandalized, one has to have a whole view of things, which not many of us have.”

A “whole view of things.” That gave me pause. And it reminded me of why I am not writing solely to a Christian audience, or even a religious one. But I do think my book will appeal to people with a conscience that is attune to both art and spirituality. But also one that doesn’t recoil from graphic sex and violence. Even so, in writing scenes that would be considered R-rated (and which I wouldn’t want my nine-year-old Goddaughter to read) I must also consider taste. Again, I return to O’Connor’s words:

“About bad taste. I don’t know, because taste is a relative matter. There are some who find almost everything in bad taste, from spitting in the street to Christ’s association with Mary Magdalen. Fiction is supposed to represent life, and the fiction writer has to use as many aspects of life as are necessary to make his total picture convincing. The fiction writer doesn’t state, he shows, renders. It’s the nature of fiction and it can’t be helped. If you’re writing about the vulgar, you have to prove they’re vulgar by showing them at it. The two worst sins of bad taste in fiction are pornography and sentimentality. One is too much sex and the other too much sentiment. You have to have enough of either to prove your point, but no more.”

I consider the passages in my novel that have received both positive and negative comments at writing workshops over the past two years. There is rarely a consensus on these issues, probably because, as O’Connor said, taste is a relative matter. For every person who says, “This is too graphic. Leave more to the reader’s imagination,” there is another who says, “Terrific images. I’m there.” But since all the faculty, mentors, meta readers and my freelance editor have given thumbs up to most of the choices I’m making about rendering the vulgar along with the beautiful, I’m not censoring the sinful actions in the novel very severely.

As O’Connor continues:

“Art is… something that one experiences alone and for the purpose of realizing in a fresh way, through the senses, the mystery of existence. Party of the mystery of existence is sin.”

As I wrap up my novel revisions, I take encouragement from more of O’Connor’s wisdom:

“When you write a novel, if you have been honest about it and if your conscience is clear, then it seems to me that you have to leave the rest in God’s hands. When the book leaves your hands, it belongs to God. He may use it to save a few souls or to try a few others, but I think that for the writer to worry about this is to take over God’s business.”

Of course, before it gets into God’s hands, it has to go through an agent and a publisher, and the publisher’s editor. Here’s to finding folks who share my taste in writing about the mystery of existence.

I’m eager to read your novel, but not just for the story. It’s so interesting to think about how you have built in and the choices you made, the story behind the story. Good luck! Can’t wait.

Thanks, Laura. I’m getting anxious to be finished and am honored that you want to read my book. It’s quite a journey!

Thanks for the reminder that it can’t all be sweetness and light . . . not even if one were writing for 15-year-old girls.

Thanks for reading, and for commenting, Mary. Keep telling those stories! (I just visited your site and enjoyed it.)

Well said. Best wishes for your novel.

Thanks so much for stopping by, Mary Alice. I’m honored!