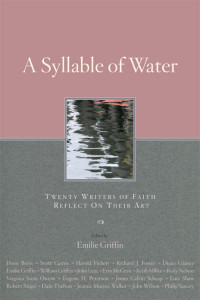

Last summer I discovered a wonderful book of essays on writing: A Syllable of Water: Twenty Writers of Faith Reflect on Their Art. My friend, the Orthodox poet and writer, Scott Cairns, has a wonderful essay on poetry in the book. I did a post about one of the essays, “The Snarl and Gnarl of Revision,” last July. And another post that same month about Doris Betts’ essay, “The Novel Taking Form,”—“How We Use Our Words: Christian is Not an Adjective.” Today I’ll share a few gleanings from Rudy Nelson’s chapter, “Getting It Right: On Research.”

Last summer I discovered a wonderful book of essays on writing: A Syllable of Water: Twenty Writers of Faith Reflect on Their Art. My friend, the Orthodox poet and writer, Scott Cairns, has a wonderful essay on poetry in the book. I did a post about one of the essays, “The Snarl and Gnarl of Revision,” last July. And another post that same month about Doris Betts’ essay, “The Novel Taking Form,”—“How We Use Our Words: Christian is Not an Adjective.” Today I’ll share a few gleanings from Rudy Nelson’s chapter, “Getting It Right: On Research.”

Rudy and Shirley Nelson are writing partners who identify themselves as “storytellers,” saying:

The core of any of our work has always been story, though the context might be history or biography or journalism, and the medium print or film. But storytelling has not excused us from the necessity of research, even when fiction itself has been the focus.

And that’s where I find myself today, over half way through my second month of work on a new novel, The Secret Book Club. Several folks asked me how many words I wrote during my month-long writing retreat at Seagrove Beach in February. I refused to answer, because I don’t think the word count is a reflection of the amount of work going into the book, especially this early in its genesis. Much of my time was (and still is) spent on research. It’s going to be a slow process for this particular project, because I want to accurately capture the culture of the setting—a cult-like group of people living in the 1970s South. And as Nelson says of their work, “Actually we’ve never begun any project in a vacuum,” neither have I. My first novel, Cherry Bomb, contains many elements of my own life. The Secret Book Club will be an even more reflective novel. But that doesn’t mean that much research isn’t required, as Nelson continues:

And that’s where I find myself today, over half way through my second month of work on a new novel, The Secret Book Club. Several folks asked me how many words I wrote during my month-long writing retreat at Seagrove Beach in February. I refused to answer, because I don’t think the word count is a reflection of the amount of work going into the book, especially this early in its genesis. Much of my time was (and still is) spent on research. It’s going to be a slow process for this particular project, because I want to accurately capture the culture of the setting—a cult-like group of people living in the 1970s South. And as Nelson says of their work, “Actually we’ve never begun any project in a vacuum,” neither have I. My first novel, Cherry Bomb, contains many elements of my own life. The Secret Book Club will be an even more reflective novel. But that doesn’t mean that much research isn’t required, as Nelson continues:

However valuable personal experience may be as a head start, it has always quickly led us into unexplored locations. And that’s the safest place to be. For research to be done from the right perspective, it’s best to consider yourself a blank tablet.

Nelson talks about the mixed blessing that Google brings to a writer’s research:

As one Google entry leads to another and another and yet another, one has to decide when the search has gotten out of hand…. How far back should we go? Or, depending on the subject, how far in? …. So when should research stop and writing begin?

I’ve only read three books in my (growing) stack of books to read for this novel. I’m a slow reader, so that’s actually a lot of reading for me during a six-week period. Especially since I take notes as I read. And I’ve drafted two chapters of my novel as I’ve been reading. I think the work will continue this way—the reading and writing finding a rhythm together. Nelson approves:

Those two parts of the creative process should walk hand in hand from start to finish…. Robert Stone, whose novel A Flag For Sunrise captures the insidious threat of violence in Central American during the 1970s, says that a novelist must assume, above all, “the responsibility to understand. The novel that admits to a political dimension requires a knowledge… intuitive or empirical, of the situation that is its subject.”

Much of the knowledge I bring to my work-in-progress is intuitive. I wouldn’t approach a subject which hadn’t touched my life in some way, at least not for a novel. Unlike the journalist who writes about assignments that may or may not have anything to do with her own life, the novelist can choose—and I make that choice—to “write what you know.”

Nelson quotes Barbara Kingsolver as saying:

Write a nonfiction book, and be prepared for the legion of readers who are going to doubt your facts. But write a novel, and get ready for the world to assume that every word is true.” The implication, of course, is that in fiction not every word is “true.” In the imagined world the novelist has created, versimilitude—the literal factual equivalency of that imagined world to the external world of our daily lives—is often in short supply…. Fiction explores a far deeper and more important level of truth than versimilitude can touch.

And so, novelists often do must as much research as nonfiction authors. And we do it, as Nelson says, in order to “represent the true breadth of that culture accurately.”

The characters in The Secret Book Club are fictional. I am fabricating their lives, but I am using patterns and materials that were common in the South of the 1970s—especially the books that the women read and discuss together. They are NOT the books that my friends and I were reading back then, because we didn’t have a secret book club. But if we had…. well, the books I’ve read so far are:

The characters in The Secret Book Club are fictional. I am fabricating their lives, but I am using patterns and materials that were common in the South of the 1970s—especially the books that the women read and discuss together. They are NOT the books that my friends and I were reading back then, because we didn’t have a secret book club. But if we had…. well, the books I’ve read so far are:

The Easter Parade by Richard Yates

The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty

The Women’s Room by Marilyn French

Next up? (Haven’t decided the order of these four yet):

Fear of Flying by Erica Jong

The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin

I’m OK—You’re OK by Thomas Harris, M.D.

Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

Lots of reading, but as a novelist, I have the responsibility to understand the culture I’m writing about. So here I go… to the books.