We don’t even know.

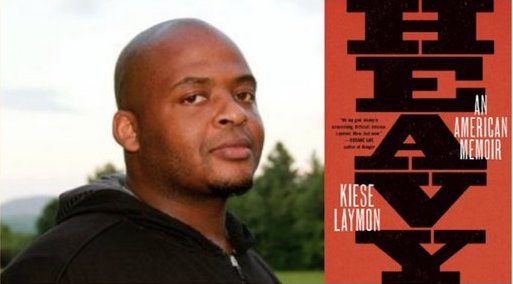

Today I finished reading one of the most powerful memoirs I’ve ever read. Ever. I am both honored and ashamed to say that the author, Kiese Laymon, is from my home town, Jackson, Mississippi. Honored because his words are beautiful and powerful. Ashamed because they are true, and many of his words apply to me and to my fellow white Mississippians and white Americans. His memoir is titled Heavy: An American Memoir. I’m not going to write an actual book review here. If you want to read a good one, read this one on NPR by Martha Ann Toll.

This isn’t the first contemporary book I’ve read by a fellow author from Jackson, or even by an African-American author from Jackson. Last year I read The Hate You Give by Angie Thomas. I wish I had known about both Angie and Kiese when I was recruiting authors for the anthology I edited last year, Southern Writers on Writing, which only contains four essays by African American authors. My bad.

I also wish I had known Jeffrey Blount, whose wonderful book The Emancipation of Evan Walls I reviewed here recently. And Jessie Starks, Pontotoc native who recently published her debut novella The Lynching Calendar.

Growing up in Jackson, Mississippi, in the 1950s and coming of age in the turbulent 1960s, you would think I would be more aware and informed about the plight of my fellow Mississippians of color. You would think I would know. But as Kiese and his friend LaThon say over and over to one another, and as Kiese captures their words so powerfully in Heavy:

They don’t even know.

We don’t even know. I certainly didn’t know when I was growing up white and privileged in Jackson. We had a black maid, Lillie Bell, who took care of my brother and me in the 1950s while our mother was teaching school. I do remember having an early rebellion against whatever social propriety said our maids would call the children in their care “Miss Susan” and “Mister Mike.” We were of course taught to call adults “Mr.” or “Mrs.” last name, or in the case of close friends of our parents, we might say “Mr. Bill” or “Miss Jane.” Since Lillie Bell was obviously much older than me, it didn’t make sense that I would call her by her first name and she had to call me “Miss Susan.” I have a vague memory of discussing this with my mother, whose answer was something along the lines of “it’s just the way it’s always been done.” And my parents were not racist. But like me, they just didn’t even know.

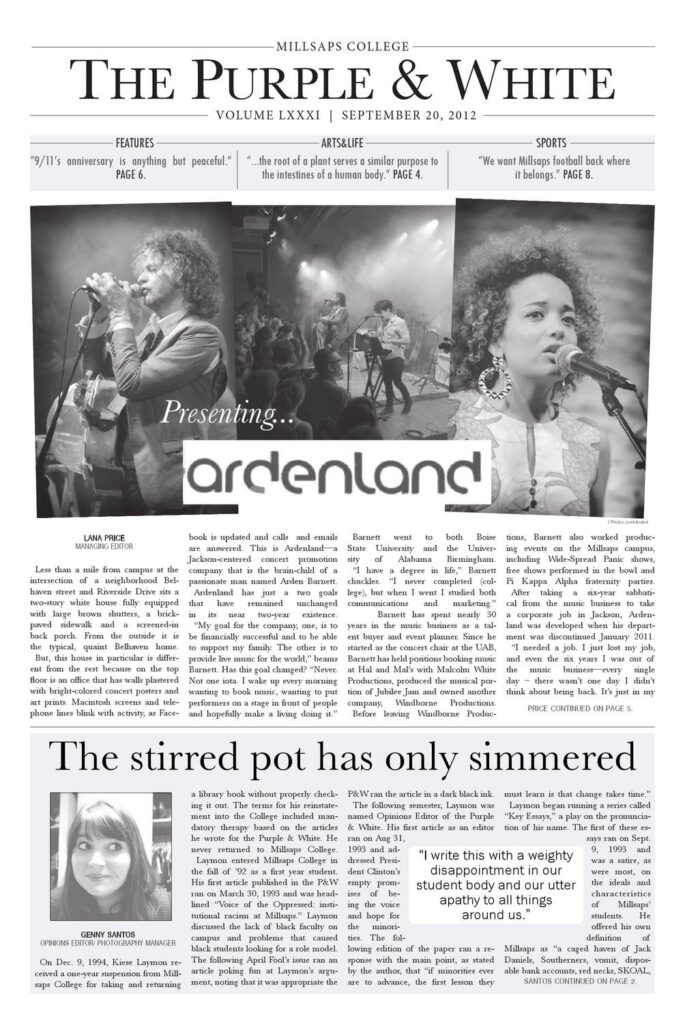

There’s so much more to this book than a memoir about race. I identify with Kiese’s struggles with weight, with eating disorders, with abuse, with forgiveness. But that’s really all I can “identify” with here, since I’m not a heavy black boy or man. The settings were so familiar to me . . . from some of the schools Kiese attended where my brother and I also had friends several decades earlier, to neighborhoods around Millsaps College, where my brother was a member of Kappa Alpha fraternity in the early 1970s, also years before his fraternity brothers would respond violently to an essay Kiese published in the school paper called, “Institutional Racism at Millsaps.”

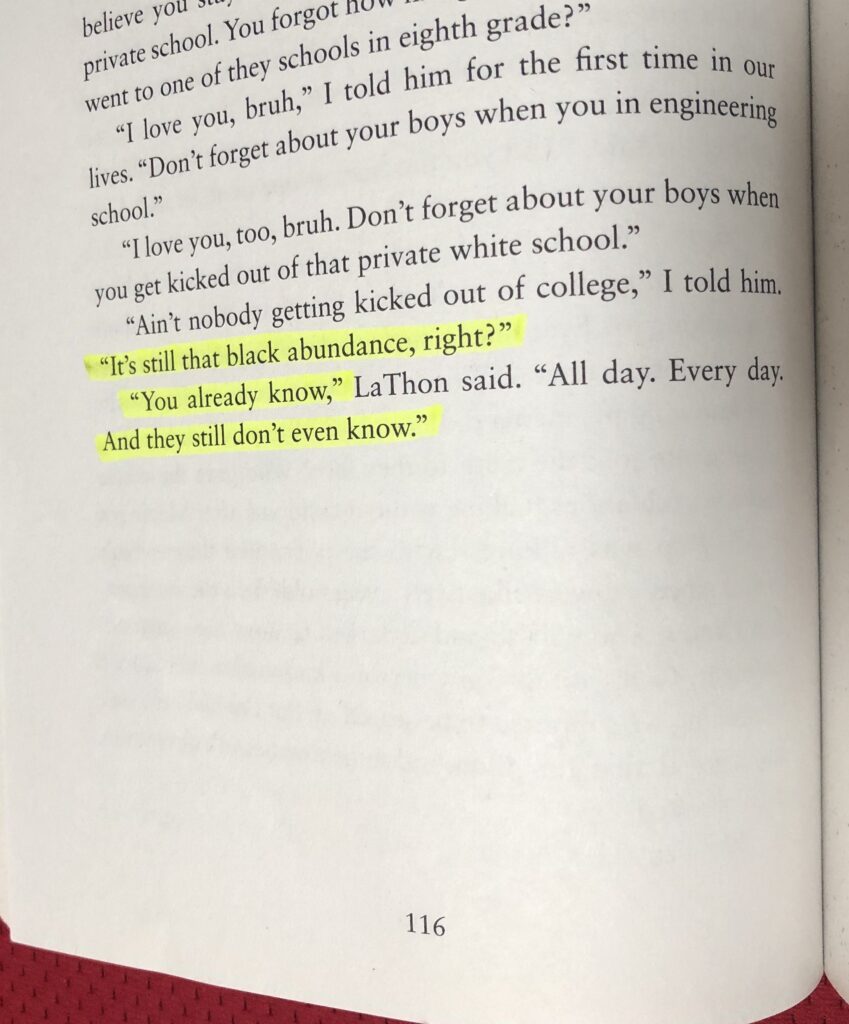

Years earlier Kiese and his friend LaThon’s eighth-grade schedules were changed to keep them from sharing any classes at predominately white St. Richard’s Catholic School. Their white homeroom teacher freaked out when LaThon was slicing up his grapefruit with a plastic knife. LaThon was the one who penned the term, “black abundance,” and when the boys were able to see each other during recess, at lunch, or after school, they would hold each other close.

‘It’s still that black abundance?’ I asked LaThon.

‘You already know,” he said, annunciating every syllable in a voice he’d never used before walking into his homeroom.

There are endless reasons to read this book. It’s important. It’s a gift to all of us who will listen, who will try to understand and to make a difference. It’s a gift to those of us white Americans who don’t consider ourselves to be racist, like me. (My son-in-law is African American, and is one of the best men I know, of any race.) But it’s also a gift to all of us who are broken (and how many of us are not?) and in turn, have broken others. One of the last things Kiese said to his mother (and btw the book is written to his mother, who was abusive to him) was this (in a rare moment of him speaking in uncorrected dialect with his mother, a highly educated professor herself):

“We all broken,” I said, “Some folks do whatever they can not to break other folks. If we’re gone be broken, I wonder if we can be those kind of broken folk from now on. I think it’spossible to be broken and ask for help without breaking other people.”

One final thing I share with Kiese is a wonderful relationship with a grandmother. Mine, “Mamaw,” was my mother’s mother, who lived in Meridian all the years that we lived in Jackson. As Kiese’s grandmother got older and began to confuse him with his Uncle Jimmy, Kiese reflected on that loss, and on memories:

“I will wonder about the memories Grandmama misplaced, forgot, or just lost from the time I started this book until I finished. I still wonder if the memories that remain with age are heavier than the ones we forget because they mean more to us, or if our bodies, like our nation, eventually purge memories we never wanted to be true.”

And finally, one of his last conversations with her:

“Grandmama will ask me if I am okay. ‘No,’ I will tell her. ‘I’m not sure any of us are okay.'”

Kiese Laymon is now Ottilie Schillig Professor in English and Creative Writing at the University of Mississippi, where I was once an English major, before Kiese was born.