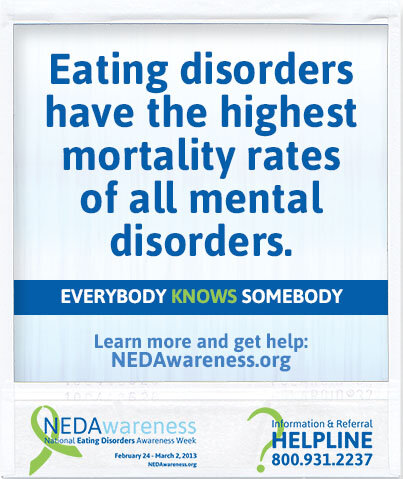

According to an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry (2009):

According to an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry (2009):

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

And yet, this mental illness was left out of the Mental Health First Aid training course I took last weekend, sponsored by the Church Health Center here in Memphis. They used to include Eating Disorders, but the course took longer than one day, so they cut it out. The mental disorders they included in the eight-hour course were: anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia. I can see why they chose these disorders for the course, as each of them have specific things a person can do to help—mental health first aid—when they see someone struggling with an anxiety or panic attack, severe depression, substance abuse, and behavior that is dangerous to themselves or others. For someone with an eating disorder, the symptoms don’t always present in such obvious forms. And “mental first aid” for persons with this disorder is a bit more complicated.

Thankfully there’s a whole chapter devoted to eating disorders in the Mental Health First Aid USA manual they gave us at the training, and I came home and read it right away. If you’ve been reading my blog for very long, you know that my interest in this disorder is very personal, as I’ve suffered from eating disorders for most of my life. I don’t believe that my level of disordered eating has placed me in a life-threatening situation—the way that anorexia can, on the one extreme, or morbid obesity, on the other. And for many people like me, it would be difficult for someone to know how to reach out to us with any kind of mental first aid. By the time a person’s eating disorder has become life-threatening, it seems that treatment has a diminishing chance of success.

With so much emphasis on body image in our culture, it’s not surprising that many people (especially women and girls) suffer from body image distortion and resultant eating disorders in an effort to live up to society’s standards for a thin body. This started for me when I was a young teenager and gained 35 pounds in one year as a result of hormone therapy I received following surgery when I was 16. I went from a skinny 95-pound bundle of energy (who could eat as much as I wanted and not gain weight) to a 130-pound late-blooming adolescent. (I also grew three inches taller.) By the time I got married at age 19, I weighed 140 and was depressed. My bulimic habits, which began as a teenager, continued into adulthood. I would eat in secret and lie about what I was eating. I tried various forms of exercise, and finally in 1982, I found something that “worked.” I began teaching aerobic dancing at my parents’ athletic store in Jackson, Mississippi (Bill Johnson’s Phidippides Sports) and dropped to 116 pounds pretty quickly. But my disordered eating and body image distortion only increased. Standing in front of a wall of mirrors in spandex, teaching my students, I still thought I was fat. On any day that I couldn’t work out, I wouldn’t eat. Bulimia was still part of my life, but less so with al the exercise.

When I read the chapter on eating disorders in the Mental Health First Aid manual, I recognized immediately which category I fit into. I don’t have anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (since bulimia isn’t a regular activity for me) so the third category, “Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified or EDNOS” includes Binge-Eating Disorder, which is the main thing I’ve struggled with most of my life. Whenever I post images—like this one of the Hersheys Kisses I ate on a recent binge—on social media, I get lots of responses from others with similar issues, so I know it’s fairly common. According to an article in Biological Psychiatry (2007):

When I read the chapter on eating disorders in the Mental Health First Aid manual, I recognized immediately which category I fit into. I don’t have anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (since bulimia isn’t a regular activity for me) so the third category, “Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified or EDNOS” includes Binge-Eating Disorder, which is the main thing I’ve struggled with most of my life. Whenever I post images—like this one of the Hersheys Kisses I ate on a recent binge—on social media, I get lots of responses from others with similar issues, so I know it’s fairly common. According to an article in Biological Psychiatry (2007):

A national survey of adults found that 1.2 percent had binge-eating disorder in the previous year and 2.8 percent had had it some time in their life. Approximately 28 percent of people with binge-eating disorder received treatment for mental health problems.

I think that last statistic is important, because in order to get healed from an eating disorder, I think a person needs help with the underlying cause. Again, according to the Mental Health First Aid manual (and an article in Lancet in 2003):

A range of biological, psychological, and social factors may be contributing factors. The following factors increase a person’s risk of developing an eating disorder:

Life Experiences

Conflict in the home, parents who have little contact with or high expectation of their children.Sexual abuse.

Family history of dieting.

Critical comment from others about eating, weight or body shape.

Pressure to be slim because of occupation (model, jockey) or recreation (ballet, gymnastics)

I checked “yes” for ALL of these. I could never live up to my mother’s expectations, and experienced relentless verbal abuse from her, especially her criticism of my weight, hair, and clothes. She was always dieting and talking about weight (hers and others) although she remained slim all of her life. As a cheerleader in my teenage years and an aerobic dance instructor in my 30s, I was often in situations where I felt pressure to be slim. The year I spent as a coed on the Ole Miss campus added to that pressure. I kept comparing myself to the beauty queens my boyfriend had dated before me.

The manual also says that mental disorders in family members can contribute to someone having an eating disorder. My mother definitely exhibited substance use disorder (drinking) and I have reason to believe that she was sexually abused by her father, my grandfather, who molested me when I was a little girl.

So, what’s the Mental Health First Aid Action Plan for helping someone with an eating disorder? It’s tricky, to say the least. It requires that a person wanting to reach out and help someone must learn as much as possible about the disorder first, by reading books and articles, or talking with a health professional. Then they should choose a time to approach the person they are concerned about and do so in a way that is non-judgmental and compassionate. Some tips in the manual:

Initially, focus on conveying empathy and not on changing the person or their perspective… try not to focus solely on weight or food. Rather, focus on the eating behaviors that concern you. Allow the person to discuss other concerns that are not about food, weight, or exercise. Make sure you give the person plenty of time to discuss their feelings, and reassure them it’s safe to be open and honest about how they feel.

I think this is great advice. Some things NOT to do (that I’ve experienced personally and found not to be helpful) are: (these come from me, not from the manual)

Suggest a specific diet or nutrition plan that has “worked for them.” (Unless the person is ASKING for one.)

Use words or a tone of voice that is patronizing, even in an attempt to flatter the person with phrases like, “Oh but you are beautiful just the way you are.” This is fine if you are close friends with the person, but not helpful in mental health first aid.

Like the other mental health first aid approaches, this one has guidelines for assessing the person for crisis including:

The person has serious health consequences (disorientation, vomiting, fainting, chest pain or trouble breathing, blood in their bowels, urine, or vomit, or cold or clammy skin and a body temperature of less than 95 degrees Fahrenheit.

If you come across someone with these symptoms, mental health first aid is important, and you should apply similar techniques as for other crises (the

If you come across someone with these symptoms, mental health first aid is important, and you should apply similar techniques as for other crises (the

ALGEE action plan I explained in my previous post.) But there are suggestions specifically for helping someone with an eating disorder who seems to be in a crisis. There’s too much information for me to share here, but I hope you will get the manual and read about this yourself.

I know this was a long post, and as always, thanks for reading. And of course I love to hear from you, either here or on the Facebook thread.

Here’s a post from a few years ago that has an excerpt from my essay “Eat, Drink, Repeat”:

Susan, thank you for this blog. Your honesty gives me such hope. I, too, suffer from mental illness which, over the years has manifested itself in several different ways ( as is the case with any addiction). Sad we did not understand about all of this when at Chasten and Murray, we could have helped each other – I would never have guessed this about you!

About 5 yrs ago, I went thru an intensive treatment program for women and I learned so much about myself and found my voicemail. My delima, at present, is finding a way to deal with my morbid obesity! I want/need to get away from my current living situation and find an in- patient recovery program. Do you have one you would recommend? Thank u for opening this door for all of us.

Thanks so much for writing, Kathy. I don’t personally know anything about in-patient recovery programs so I can’t recommend one. I’ll message you a contact person in Jackson who might can help. Love you!

Enjoyed your post!

Thanks, Robert.